Last week’s newsletter came and went like all the others, but I think it was my 100th! That’s cause for celebration, I think. Hooray! Thanks for being part of that, and thanks for reading Taking Bearings. The number of new subscribers has grown in recent weeks based on others’ recommendation (and something Substack has done with its algorithm, I suspect). I’m grateful for that. If you are new, check out my explanation of the newsletter to orient yourself to the themes that cycle through week by week.

This week I’m back to The Library, and I’m exploring Willa Cather’s classic novel My Ántonia. I have a large collection of unread Cather books. Last month’s interview subject, Debbie Lee, connected me with another Substack writer, Joshua Doležal, who is leading a read-along of My Ántonia. I knew I had my next library book. Read on!

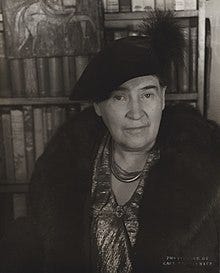

Willa Cather and My Ántonia

Willa Cather represents a set of regional writers in the West coming to grips with the rapid transformation of the region. These writers, according to some, reckoned with the West as a place with staying power, rather than a place merely to dominate.1 In other words, the West was a place to stay, not merely one to move through.

My Ántonia tells the story of the title character, an immigrant who came to the prairie as a child with her family. Ántonia confronted a series of tragedies and ultimately persisted on the Nebraska plains. Jim Burden, a childhood friend who leaves the prairie, tells the story.

I encourage you to read this book, so I won’t say much about the plot. Instead, I want to share examples of Cather’s prose—both to tempt you to gain the full experience yourself and as exemplars of depicting place effectively.

Cather’s Seasonal Prose

For someone like me who spends a great deal of time thinking about place, Cather’s prose sings best when she’s describing the landscape. She uses it to great effect; she makes it a character.

Early in the book, when Cather is getting her characters to the isolated Nebraska prairies, Cather writes memorably, “There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made.” (The material out of which stories are made, too.) I imagine using this sentence again and again to illustrate the sense Cather captures with it.

Cather illustrates seasons especially well. Many times when a chapter began after time passed, she reset the scene with seasonal portraits that offered contrasts. For instance:

Winter lies too long in country towns; hangs on until it is stale and shabby, old and sullen. On the farm the weather was the great fact, and men’s affairs went on underneath it, as the streams creep under the ice. But in Black Hawk the scene of human life was spread out shrunken and pinched, frozen down to the bare stalk.

Re-read that again and again to see how many comparisons she makes. It’s remarkable for three sentences.

Or:

When spring came, after that hard winter, one could not get enough of the nimble air. Every morning I wakened with a fresh consciousness that winter was over. There were none of the signs of spring for which I used to watch in Virginia, no budding woods or blooming gardens. There was only—spring itself; the throb of it, the light restlessness, the vital essence of it everywhere; in the sky, in the swift clouds, in the pale sunshine, and in the warm, high wind—rising suddenly, sinking suddenly, impulsive and playful like a big puppy that pawed you and then lay down to be petted. If I had been tossed down blindfold on that red prairie, I should have known that it was spring.

Writing like this paints a clear pictures and reminds writers of the many possibilities nature provides. I am confident that these kinds of scenes will stick in my mind as synonymous with Cather.

Changes on the Land and the Familiarity of Home

As a regionalist, someone interested in change in place, Cather depicts the prairies undergoing change—but is not always clear how the characters welcome that change.

The wheat harvest was over, and here and there along the horizon I could see black puffs of smoke from the steam thrashing-machines. The old pasture land was now being broken up into wheatfields and cornfields, the red grass was disappearing, and the whole face of the country was changing. There were wooden houses where the old sod dwelling used to be, and little orchards, and big red barns; all this meant happy children, contented women, and men who saw their lives coming to a fortunate issue. The windy springs and the blazing summers, one after another, had enriched and mellowed that flat tableland; all the human effort that had gone into it was coming back in long, sweeping lines of fertility. The changes seemed beautiful and harmonious to me; it was like watching the growth of a great man or of a great idea. I recognized every tree and sandbank and rugged draw. I found that I remembered the conformation of the land as one remembers the modeling of human faces.

The change here seems positive, “beautiful and harmonious.” This is the path of progress, the expected development of “nothing but land” to a developed rural landscape.

Nevertheless, the narrator still sees the land beneath that change. It remains familiar. In the final pages, a different sense appears even more closely.

I took a long walk north of the town, out into the pastures where the land was so rough that it had never been ploughed up, and the long red grass of early times still grew shaggy over the draws and hillocks. Out there I felt at home again.

What was home, it turns out, was the land itself, the unplowed place, the region’s true heart.

Closing Words

Relevant Reruns

The Great Plains are not a place I write of much at all, so I have no comparable old newsletters to link to. This may be the only other novel I’ve chosen to write about for The Library (because writing about fiction makes me nervous!). I cannot locate any other writing remotely related to this week’s newsletter, so here is a random piece of mine from 2019.

New Writing

My traveling last week has slowed my reporting and writing. Still, I wrote a couple short features about Mount St. Helens for an online encyclopedia of Washington state. They appeared last week; you can find them here and here.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

Next week is The Wild Card, which means anything can happen. Stay tuned!

A summary of this framework is found in Richard W. Etulain Re-Imagining the Modern American West: A Century of Fiction, History, and Art (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1996).

I love that book. Recently, the Atlantic put out their list of Great American Novels and DEATH COMES FOR THE ARCHIBISHOP by Cather was on there. I want to read that next.

I have long been a fan of Cather, too. Such amazing depictions of people and place. She reminds me of another wonderful writer, who wrote in a similar vein, Mildred Walker. She's probably best known for Winter Wheat and The Curlew's Cry. All her books are good.