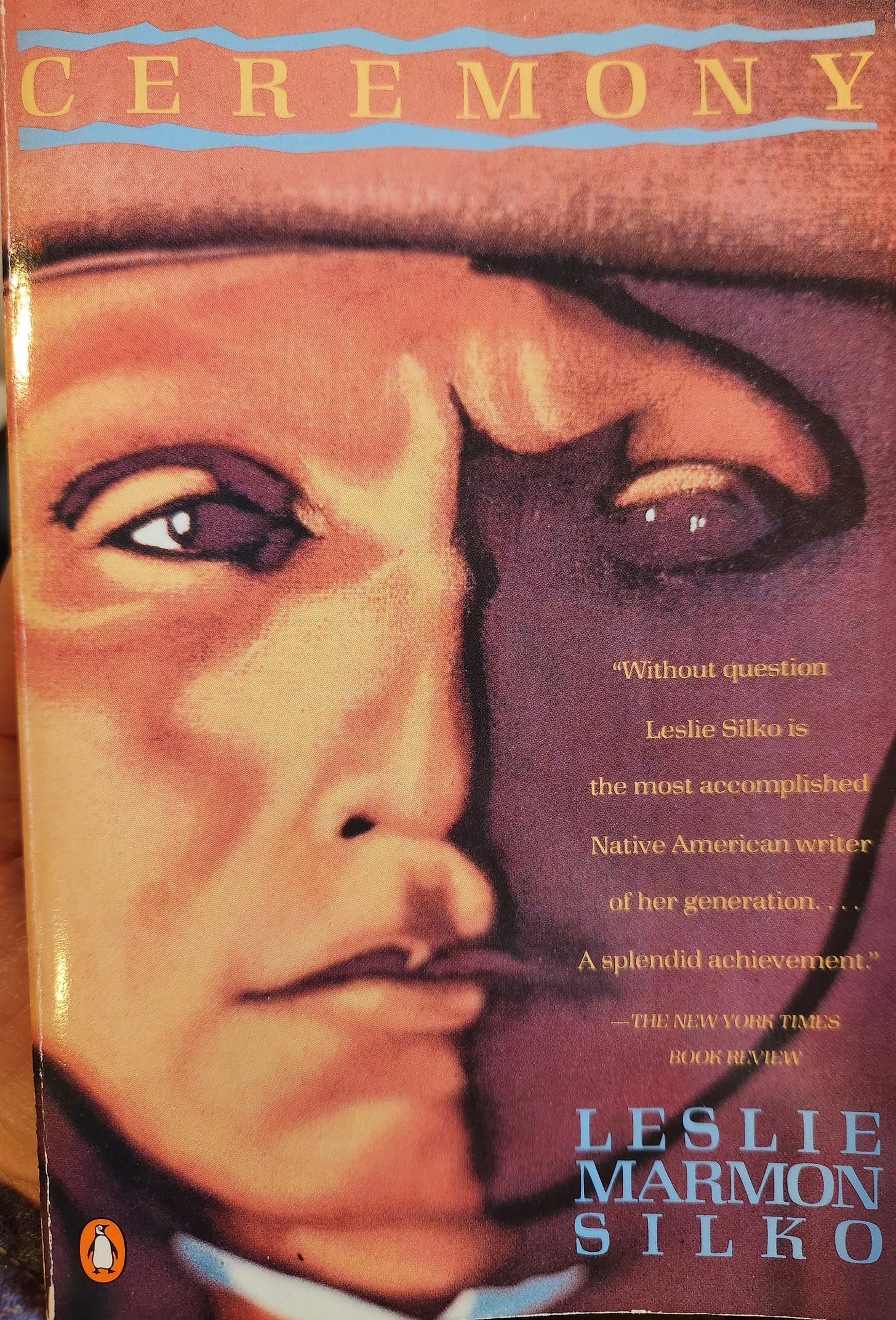

Perhaps because of the cold, wetness of oncoming winter, I veered into some Southwest reading and thinking of late. (See the past newsletter I wrote on my old research in Arizona.) Somehow, I managed to make it this long without reading Ceremony by Leslie Marmon Silko (Laguna Pueblo). Gaps in my education continually reveal themselves to me.

Ceremony is an acknowledged classic of Native American literature. Its themes rightfully belong within that select group – especially the questions of identity and belonging that permeate the novel. However, I am intrigued by its environmental components, which are not incidental, so I’m diving in with a selective reading of Ceremony for The Library this time around. Read on!

But First Some Caveats

Although novels reflect and inform history and I used them often in teaching, I feel sheepish commenting on them, as if I’m an authority. I’m not. I’m an enthusiastic reader of fiction, but I’m uninitiated as a skilled analyst of literature.

I also lack specific expertise on Indigenous history in the Southwest. Consider my reflections here, then, preliminary and superficial. Tentative, at best.

And I mean to focus on a small part of the book that spoke to some of my specific historical interests. But first, a quick introduction.

The Author and Some Context

Silko grew up in Laguna Pueblo, in west-central New Mexico. Born in 1948, she became an award-winning novelist and now resides in Tucson. Ceremony launched her reputation as a leading Native American author. In 1969, N. Scott Momaday (Kiowa) earned the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction for House Made of Dawn, the first such honor to an Indigenous author. That success established the context for Silko’s rise with Ceremony appearing in 1977.

It is notable that both Ceremony and House Made of Dawn concerned the challenges of World War II veterans returning home and locating a place in society both as veterans and Native people. The contemporary context of the Vietnam War and resurgent sovereignty movements made these themes unavoidable.

The critical and commercial success of writers like Momaday and Silko marked a new moment in literary history.

Property and Belonging

But literary history is not where my attention is directed. Although it is not a central theme of Ceremony, property plays a role.

One version of the Grand Story of the Continent is how hundreds of sovereign nations faced invasion and colonialism, a key element of which was imposing property regimes foreign to the land. Private property – a conceptual and legal innovation – took land and water and creatures out of community-based and reciprocal relationships and into one that seems most often about control and profit. Environmental historian William Cronon once quipped in a line I’ve quoted before, “A people who loved property little had been overwhelmed by a people who loved it much.”

Cronon was characterizing the situation in New England in the 17th and 18th centuries. But Ceremony demonstrates it mattered in 20th-century New Mexico, too.

The novel's protagonist, Tayo, spends part of the story tracking down cattle that escaped from – or were stolen from – his family’s control. The cattle, chosen because they were a hearty breed that might survive more easily in the desert Southwest, offered the family an economic opportunity, even independence.1 The cattle could fend for themselves across the New Mexico range.

Yet a white rancher not only possessed vast portions of the land but decided to fence it off. The Fence represents Property better than anything, I think, even more than a Deed. And so, as Tayo tracks down the cattle, he reached the fence. And he and others

knew what the fence was for: a thousand dollars a mile to keep Indians and Mexicans out; a thousand dollars a mile to lock the mountain in steel wire, to make the land his.

Sole possession. Racial exclusion. Extravagant wealth. All of these symbols stand out from these few lines, just as barbed wire stands out in an otherwise unobstructed horizon.

From the perspective of Tayo and his family and ancestors, land does not belong to people. Mount Taylor (Tsoodził to the Diné or Navajo), a sacred mountain for several Indigenous nations, stands as a ubiquitous presence in the novel, always watchful and orienting for Tayo.

It also symbolizes land more broadly. Silko writes,

They only fool themselves when they think it is theirs. The deeds and papers don’t mean anything. It is the people who belong to the mountain.

Eventually, Tayo tracked down the cattle and liberated them, cutting the fence that trapped the animals. A cowboy on the ranch – predictably, a Texan – found Tayo and threatened him before walking off muttering, “These goddamn Indians got to learn whose property this is!” Irony and tragedy collide and blend, as in nonfictional worlds.

Other environmental themes penetrate the book, especially the fact that these lands held uranium used in the nuclear weapons that ended the war Tayo fought in. However, I will save that for another time, perhaps.

Instead, I’ll end this section with a piece of wisdom shared with Tayo by his uncle, Josiah:

Cattle are like any living thing. If you separate them from the land for too long, keep them in barns and corrals, they lose something.

This sentiment hits home. Separated from land, walled off from free movement, we all lose much.

Parting Thoughts

Criticism

This brief account of Ceremony is woefully incomplete. By design. Not only am I no expert on Indigenous literature or history, but Silko has received criticism for some of the central features of the novel. A key part of Ceremony is the ceremony Tayo participates in that helps him heal from trauma. Another Laguna Pueblo writer, Paula Gunn Allen, in her article “Special Problems in Teaching Leslie Marmon Silko’s ‘Ceremony,’” details her concerns about this. Allen explained that she had been taught not to share things outside clans, because bad things occur when you do. Although I am in no position on these questions, it seemed responsible to mention this.

Savoring Words

I find value in reading fiction. It informs my view of history and helps me see worlds I would not have the eyes to see otherwise. And at times, novelists simply provide beautiful language worth savoring like this line from Silko that I enjoyed:

He breathed deeply, trying to inhale the immensity of it, trying to take it all inside himself, the way the arroyo sand swallowed time.

I hope you’ll pick up a novel this week that might offer a new perspective on things – and may it be so good that it feels like it swallowed time!

Final Words

As a historian of public lands, I have written occasionally explicitly and often implicitly about the imposition of private property regimes on Indigenous land. Much of my opening chapter in Making America’s Public Lands covers this. A briefer version is included in a few paragraphs included in this piece, too.

As always, you can find my books and books where some of my work is included at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

Next week is The Wild Card, and, just between you and me, I haven’t selected my topic. Stay tuned!

One of my graduate mentors studied this development. See Peter Iverson, When Indians Became Cowboys

"Fiction is a lie through which we tell the truth." -- Albert Camus