Last March, I attended a virtual town hall where my local state legislators assessed the year’s legislative session. “We make incremental progress on everything and anything here in the House and the Senate, I think,” one of them said. “Our democracy works because good ideas take time and bad ideas, hopefully, die quickly.”1

If only this were so.

Last week, the State of Utah stretched toward a bad idea that has faded many times but won’t stay dead. The state submitted a lawsuit to the US Supreme Court to find out if the federal government may control unappropriated public lands indefinitely. In Utah, this includes about 18.5 million acres administered by the Bureau of Land Management.

Utah’s case goes against the Constitution, federal legislation, and more than a century’s worth of tradition and law. But it feeds persistent frustrations and grievances, which makes it a popular political strategy in some quarters.

For The Classroom this week, I wanted to dive into some of this history. Read on!

Enabling Acts and the Remaining Public Lands

In my book Making America’s Public Lands (new out in paperback!), I spell out the ways American founders understood the public domain and the policies put in place to move it into private hands. This approach to land privatization was the dominant goal through the 19th century. It’s briefly recapped here. An even shorter version is: the national government gave and sold land to soldiers and railroads and individuals.

As the nation incorporated more of the continent through purchase, war, and treaties, the nation organized formal territories — Utah Territory, Washington Territory, and the like. In time, once populations reached certain standards and state constitutions were written (and it suited national political priorities), those territories became states. For most states, an “enabling act” was the legal mechanism to transition from a federal territory to a US state. Most of these enabling acts used standard language to address standard issues.

In Utah’s own Enabling Act, 7 of the 20 sections (by my count) deal with land in some way, much of it concerned land the federal government gave the state to use to fund schools and universities, as well as hospitals, penitentiaries, and asylums. This amounted to more than a million acres freely given by the national government for the state to profit from. At the end of Section 12 came the key line: “The said State of Utah shall not be entitled to any further or other grants of land for any purpose than as expressly provided in this Act.” The state Constitution also states: “The people inhabiting this State do affirm and declare that they forever disclaim all right and title to the unappropriated public lands lying within the boundaries hereof.”

If I were a textualist, I’d read these lines as saying Utah is entitled to no more federal land within the state besides the land already given.

Where I live in Washington, the case is the same. The Enabling Act here provided the state half a million acres for various institutions and used the same phrasing as in the Utah law.

Much of these new states remained in the public domain at the time of statehood. That is, the federal government still owned millions of acres within their boundaries. Homesteaders still made claims on these lands for many more decades. States remained interested in those lands, because they received five percent of the proceeds on any sale of public land to support schools.

Soon, the conservation movement started protecting parts of the remaining public domain as national forests, parks, monuments, and refuges. Lands that did not get sorted into those categories — what Utah is calling the unappropriated lands — fell under the administration of the Bureau of Land Management by the mid-20th century. Utah’s lawsuit suggests it is entitled to these lands.

Simmering Rebellions

Utah is not inventing this out of whole cloth in 2024.

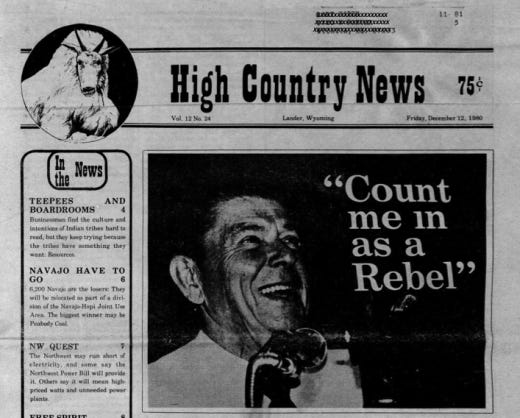

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the so-called Sagebrush Rebellion gave voice to westerners who disliked federal land management. The movement was not the first one to object to the public land system, but it was the loudest to date.2

It started in Nevada, whose Assembly passed a bill in 1979 that asserted its “strong moral claim upon the public land retained by the Federal Government withing Nevada’s border.” It short order, the legislature claimed its authority over almost 50 million acres. These ideas found a fertile seedbed throughout the West and within of the rising New Right symbolized by Ronald Reagan’s election and his appointment of James Watt to head the Department of the Interior. Despite widespread attention and key allies in high positions, states did not gain control over any of these lands.

During this rebellion and the decades since, the anti-public lands movement developed a series of specious arguments that it has recycled and repackaged every time the issue flares (which usually is when Democrats occupy the White House).3

These arguments can be slippery. I came across one politician’s explanation from a decade ago for why Oregon deserved the federal lands within its borders. He pointed to the enabling acts and asserted there was a “contractual expectation” that the federal government would sell the rest of its land.4 Two paragraphs later he upgraded this expectation to to a “contractual promise.” Then, he totally invents a section of the enabling acts that directs any unsold land to be “returned to the state.”5 You know it is an invention because none of these lands ever were the state’s to be returned to! (Plus, you can read the enabling acts and never find this direction — at least I’ve never been able to parse the law into saying this.)

At the base of these arguments is a simple expression of frustration: “We don’t like how federal lands are managed.” OK. But it is a leap to then conclude: “The federal government has no right to maintain control over public lands.”

Bad Ideas

There has been some good media coverage on the lawsuit (Salt Lake Tribune and High Country News), and

produced a great take down at The Land Desk which I found somewhat cathartic to read. Thompson’s perspective: “It’s all a vain and vacuous spectacle aimed at riling up the extreme right wing that is increasingly calling the shots in Utah, Wyoming, and Idaho.”As a historian, I don’t prognosticate (despite questions from virtually every public audience I speak to asking me to predict the future). I fall back to the past and have always been confident that history and law stood on the side of public lands. The evidence is overwhelming and clear. Yet, the last few years have shaken my faith. Fidelity to history, law, facts no longer seems to be the guide I have relied on.

Still I hope. I hope this bad idea finally dies.

Closing Words

Relevant Reruns

I linked to two earlier newsletters above. This one also uses Utah as a starting point to discussion public lands controversies. I wrote this blog post for Oxford University Press, providing some overview of a then-current controversy. These both strike similar chords to this week’s offering here.

New Writing

Still at work.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

The Field Trip returns next week. Stay tuned!

The speaker was Clyde Shavers.

William L. Graf’s Wilderness Preservation and the Sagebrush Rebellions (Savage, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1990) offers a handy guide through four rebellions.

A useful refutation is John D. Leshy’s “Are U.S. Public Lands Unconstitutional?,” Hastings Law Journal Vol. 69 (February 2018): 499-582.

I’m not a lawyer, so I may not understand the subtlety. But the contracts I’ve signed include “obligations,” not “expectations.”

I don’t wish to direct traffic to this site, but you can reply to this if you need a citation.

Hypocrisy never stopped a good lawsuit.

I think it might not be the best thing for states to administer these lands, because states are easily controlled by a small group of rich elites. I just wonder then, what is the point of even having state boundaries and forming a state, if the federal government still owns 80% of the land in Nevada for instance? Is Nevada a state in concept only?

It just seems like a weird and unequal set up. The states have to request permission to become a state from the very entity that wants to keep most of their land. So they end up accepting draconian statements like the one in the Utah constitution. I'm sure you're right about the legal aspects, I just wonder if a more federal system of shared responsibility for these lands might be a better solution. One that protects the lands from greedy and irresponsible people in states and allows the states to push back against federal policy.