Opposing Monumental Conservation (The Classroom)

"The most important piece of preservation legislation ever enacted."

Welcome to Utah!

During the first week of November, I got into the shuttle that was going to take me from the Salt Lake City Airport to Provo. We pulled away from the curb in snowy rain-rainy snow with low clouds that hid the mountains that surround the city. The driver asked why I was in town, and I explained I was lecturing about the history of public lands at Brigham Young University.

“The public lands were alright until the Antiquities Act; it just goes too far,” or something to that effect, was his initial reply.

Since the law went into effect in 1906, I gathered things had been bad for quite some time in Utah.

“The government owns 95% of Utah,” he informed me. (In fact, federal lands constitute 63% of Utah, but I gathered that accuracy might not be the point.)

Utah competes with Nevada for ground zero for anti-public lands sentiment. I knew that before I got to the Beehive State, of course. I did not want to argue facts or values with the man in charge of navigating through the crowded highways in suboptimal driving conditions, so I said that I understood some people thought that and hoped to leave it there. He turned to the retired dentist and his family along with the very young Latter-Day Saints missionary sitting in the back.

It didn’t take long, though, for him to return to me and lecture me about how Bears Ears National Monument—created with the Antiquities Act—had been a bad idea. It was ok to protect “hieroglyphics” (Oh dear!) he told me, but not all the rest. The government took land (it didn’t) and included too much extra land around the “petroglyphs” (thankfully he corrected himself) that it took hours and hours to get anywhere. Towns were going to disappear (they won’t). The soliloquy went on a little longer, but I had stopped listening closely.

My disposition is not to argue, and my upbringing (which I can usually summon) leads me not to be impolite. So I was able to keep quiet.

Ironically, one point of the lecture I was planning to deliver was that we need to sit around tables—figurative or real—to see and share different points of view if we are ever to act politically in the world. (I explored this idea first here.) My driver had not asked me to sit with him at a table, however; he force-fed me his ideas. I decided not to return the favor.

So, what is the Antiquities Act that riled him up so much?

Antiquities History

The history of the Antiquities Act's origins centers on the Four Corners region. Written and visual accounts of cliff dwellings and rich archaeological sites spread through the United States in the last third of the 19th century, exciting interest in such places and encouraging theft of artifacts.

To end this ransacking, advocates called for government help. A key figure here was the archaeologist Edgar Lee Hewett. When Congress finally decided to act, Representative John Lacey turned to Hewett to draft the legislation to protect land and to penalize those who took artifacts from sites. Meanwhile, the General Land Office withdrew some sites from settlement—without congressional authorization—to prevent someone from making a homestead of them.

The Antiquities Act gave the president the power set aside monuments with "historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historical or scientific interest that are situated upon the lands owned or controlled by the Government of the United States." They were supposed to be "confined to the smallest area compatible with the proper care and management of the objects to be protected." The law applied uniformly across all types of public land and also authorized the federal government to accept donations.

The power and mandate were broad but not extraordinary for the era. In 1891, Congress had given the president the power to reserve forests to keep them from being settled or exploited. Now, it gave presidents power to create monuments. This provided flexibility when Congress acted slowly—as was its tendency. According to the historian Hal Rothman, this made the law, "The most important piece of preservation legislation ever enacted."1

Antiquities Controversies2

Controversy 1: Grand Canyon

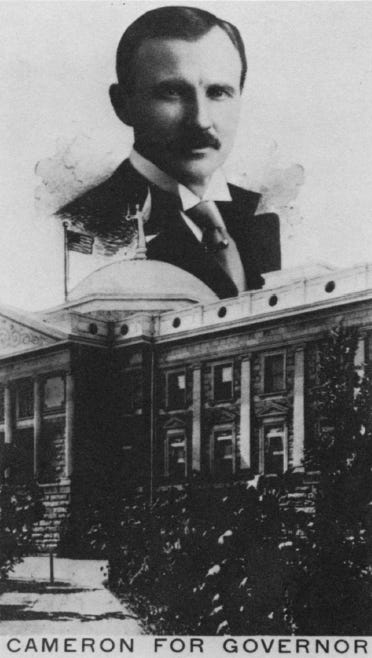

Ralph Cameron was a character, and not altogether honorable, I think. He was a Republican politician from Arizona a long time ago. Entrepreneurial, Cameron staked a "mining" claim on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon in 1902 (and a few others elsewhere). Only it wasn't a mining claim; he sought the property to profit off the growing tourist trade to the Grand Canyon. Once it had been turned into a forest reserve in 1893, the only way to carve out a private property claim was through mineral law (I wrote a bit about that here and here). Hence, Cameron's strategy. However, he lost his claims, because there was no evidence of paying minerals.

Undeterred by immediate practicalities, Cameron also charged that President Theodore Roosevelt exceeded his authority when creating Grand Canyon National Monument in 1908. There were no grounds for creating the monument, Cameron insisted. And he persisted all the way up to the Supreme Court who finally ruled in 1920, noting that the Grand Canyon most certainly counted as an "object of unusual scientific interest," as required by the Antiquities Act. The Court scoffed at Cameron's self-serving claim the Grand Canyon was an insignificant scientific object:

It is the greatest eroded canyon in the United States, if not in the world, is over a mile in depth, has attracted wide attention among explorers and scientists, affords an unexampled field for geologic study, is regarded as one of the great natural wonders, and annually draws to its borders thousands of visitors.

Of course, the Grand Canyon satisfied statutory requirements. This would not end challenges to the Antiquities Act.

Controversy 2: Jackson Hole

The second Roosevelt president, Franklin, created a second controversy in Wyoming. In 1943, he established Jackson Hole National Monument. The monument connected the lowlands of the valley to the mountains where, in 1929, Congress established Grand Teton National Park.

The conservation history here is complicated. John D. Rockefeller Jr. used the Snake River Land Company to buy up 35,000 acres of private land intending to give it to the federal government, something he had done before. Although the area contained a national park, national forests, and a national wildlife refuge (and a smattering of state lands nearby), locals were unhappy about Rockefeller and the new national monument that attempted to secure public access and open space.

Ranchers were upset their traditional route into the mountains was now blocked—although they defied the rules and drove their cattle across the new monument anyway. The Forest Service was angry, because President Roosevelt took nearly a quarter-million acres to make the monument. And local politicians felt betrayed and used this event to mobilize against federal conservation measures broadly. Bernard DeVoto, a Harper's columnist, used the Wyoming pols' actions as evidence of their general anti-federal conservation chicanery. (More about DeVoto in a couple weeks in Taking Bearings.)

The State of Wyoming went to court, predictably, charging that the area Roosevelt put in the national monument was "barren" of any feature that satisfied the Antiquities Act. The district court did not want to argue about whether the area's historic value was or was not substantial enough to qualify for preservation. But Wyoming also claimed that the Executive Branch exercised too much power. And here the district court had more to say:

if the Congress presumes to delegate its inherent authority to Executive Departments which exercise acquisitive proclivities not actually intended, the burden is on the Congress to pass such remedial legislation as may obviate any injustice brought about as the power and control over and disposition of government lands inherently rests in its Legislative branch.

In other words: the Legislative Branch (i.e., Congress) gave the Executive (i.e., the President) the power; it was up to Congress to take it back.

A short time later, that's what happened, to a limited extent. Congress combined the national park with the national monument—a process that required some compromises. One of them ended presidents' power to declare national monuments in Wyoming. (A similar limitation eventually went into effect for Alaska for monuments greater than 5,000 acres, which you can read about in an article I've written about the Antiquities Act.)

Controversy 3: Bears Ears

Bears Ears National Monument became a cause célèbre or bête noire, depending on your position, late in the Obama Administration. Bears Ears includes a couple million acres in southeastern Utah rich in historical and cultural meaning for Indigenous peoples of the area. The area, mostly under the Bureau of Land Management's jurisdiction (i.e., already federal land), faced uncertainty with competing demands and ideas for its future protection or development. A Republican Congress worked slowly and eventually proposed national conservation areas for the region within what it saw as a collaborative framework. However, the plan favored grazing and energy development and drove away several of the partners (e.g., The Nature Conservancy). The proposed solution also effectively ended the presidential power in the Antiquities Act.

In response, the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition asked President Obama to create a national monument. He did in the last month of his presidency, although with a smaller tract of land than the tribal groups requested. This example, far from being unusual or unprecedented, combined something new (i.e., Native-initiated) with something very old (i.e., presidential action following congressional inaction) and proved controversial (at least to some) for familiar reasons.

The controversy heated up when Obama's successor ordered the Department of the Interior to review all national monument designations beginning with Bill Clinton's and eventually reduced Bears Ears National Monument by 85 percent (and nearly halved Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah). Conservationists filed lawsuits arguing against this action, but it became moot when, following Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland's recommendation, President Joe Biden restored the Bears Ears monument and established a co-management arrangement with local tribes.

Opposition to a national monument was not new with Bears Ears. Its massive reduction (and then reversing that) was. Because the Biden Administration restored Bears Ears, the courts never weighed into the latest round of questions about the very nature of American government. I am confident this will not be the last opportunity to do so.

Driver Redux

To be fair, my driver spoke with more insistence than hostility. He was not combative. And his antipathy to the Antiquities Act is as old as the law itself. He was not unusual—merely a good reminder that I was in Utah and there, national monuments represent a multiplicity of values.

Sources

In addition to reading the Antiquities Act and legal decisions (and sources linked above), I relied on David Harmon, Francis P. McManamon, and Dwight T. Pitcaithley, eds., The Antiquities Act: A Century of American Archaeology, Historic Preservation, and Nature Conservation; John D. Leshy, Our Common Ground: A History of America’s Public Lands; Robert W. Righter, Crucible for Conservation: The Struggle for Grand Teton National Park; and Hal Rothman, America’s National Monuments: The Politics of Preservation.

Closing Words

Normally, I offer readers links to some of my writing or public lectures. This is Thanksgiving Week, so I’ll spare you the suggestions. Instead, I encourage you to read for pure pleasure.

Taking Bearings Next Week

I’ll be back next week for The Field Trip (please read the About page to learn about my rotating weekly topics), and I’m going local with a visit to my county’s historical museum. Until then, I’m thankful to you for reading, and please consider sharing Taking Bearings.

Hal Rothman, America’s National Monuments: The Politics of Preservation (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1989), xi.

A partial recounting.