This week’s newsletter builds on the previous issue of the Wild Card, “The Varieties of Historical Genres.” There, I shared some book recommendations but used them to show different approaches to writing history. This time I’m doing something similar but thinking about some of the purposes of writing history.

Read on!

Belying the Plainness of “History”

“What do you do?”

“I’m a professor.”

“What do you teach and research?”

“History.”

For decades, I participated in countless versions of this exchange. These days, I’m trying to get used to a new one:

“What do you do?”

“I’m a writer.”

“What do you write?”

“History.”

Although they take slightly different paths, these conversations end up with that same word: history.

The word looks and sounds identical, but I’m here to declare that “history” masks remarkable diversity. That’s obvious when considering history’s subject matter. Everything and all places have histories, after all, and history begins with the dawn of people (and that doesn’t account for “natural history” which goes back to the dawn of dawns!). But I’m interested here more specifically in some of the distinct purposes of history writing.

I was mulling this over lately and thinking about my own relationship to writing history now and earlier. I wondered, What have I tried to do with my history writing? Such a self-inquiry could unwind in unwieldy directions. To give it form, I zeroed in on verbs. Like any good writer, I know that action governs our sentences, so, perhaps, it shapes history, too. I started brainstorming verbs that characterized multiple ways writers of history might approach their work.1

Here’s a start.

History to Teach

I attended graduate school intent on becoming a professor, because I wanted to teach. I knew I would need to write, but I thought little about that when deciding on my career. I wanted to teach, first and last. But inclinations and circumstances change, and as my career unfolded, I wrote more and more. Still, I think of myself as a teacher first. So, often – and I suspect you see abundant evidence in these newsletters – when I write, I’m trying to educate or inform.

The assumption here is that my audience doesn’t know something and I might have knowledge that I can share. To educate or inform is basic; it undergirds any type of history. It’s inescapable. In fact, I find it impossible to conceive of any brand of history that doesn’t teach in some way. But although it may be necessary, it is often insufficient alone. You wouldn’t want a house with only a foundation and its framing.

History to Intervene

Historians who aim to influence their professional field or make an impact in the academic world need to approach their history writing differently. When they send their articles and books to editors, they are not aiming only to educate and inform, because their audience – other historians and related scholars – know quite a bit already about the subject matter. Specialists aim to intervene and contribute to an existing body of knowledge, often theoretically or methodologically. That is, they show how theoretical insights shed new light on past phenomena or how a past event might require preexisting theories to be adjusted. Or, they develop or deploy a novel methodology. Currently, for instance, we are experiencing a revolution because of new digital technologies being applied to historical data.

These advances ask new questions and examine the past in always changing ways, opening up new vistas. They remain valuable for professional historians, essential even. However, the vast majority of people who are interested in history casually (and I’d guess the vast majority of people who are interested in history are interested in it casually) care little about the ways a scholarly book “intervenes in the literature” or “contributes to the scholarly debate.” Especially when a new approach is emerging, these arguments can be confusing and distracting to those without the background or can feel irrelevant to the reader who came to a book for other reasons than seeing the incremental advancement of history as a disciplinary field. For the specialists who already have command of the scholarly landscape, these interventions are like an entirely new scenic overlook; for the casual observer, it is more like a new sign appeared explaining how one tree in the forest previously identified as Quercus montana is actually Quercus falcata.

History to Entertain

Best-selling historians, I think, want to entertain. (I’m not sure I’ve met many best-selling historians, so I’m speculating a bit here.) Certainly, they want to inform their audiences. And I hope they also want to incorporate the most recent interpretations. But when they sit with their words, they calculate in ways that highlight how best they can entertain and surprise and delight their readers – and keep them reading.

On occasion, this can lead some writers astray. They might emphasize one element out of proportion to its influence to enhance dramatic elements. A popular historian many of my subscribers probably have read and enjoyed (and who I will keep anonymous) invented details that were ecologically inaccurate in a New York Times bestseller and award-winning book about the Northwest.2 When I detect these distortions and inventions – very minor and inessential to the book’s subject – I begin not trusting larger, more central pieces. I doubt I’ll read this author again.

But I’m getting off track.

Writing history to entertain is not something historians learn in graduate school training. I promise you I’ve never had a conversation in all my training and practice as a historian about how to entertain my readers. (Maybe how to entertain students, though.) This explains, in part, why academic books might seem “dry.” It’s a missed opportunity, maybe.

If I’m honest, I’d tell you that I might enjoy this type of history at times, but I can be skeptical about history that primarily seeks to entertain. Temptations loom large and can lure writers down a track where their choices might lean in directions that turn away from integrity and fidelity to accuracy.3 Nevertheless, writers of history might learn lessons of style from these authors who prioritize drama over minutiae, character sketches over theoretical nuances, and a good story over a lecture.

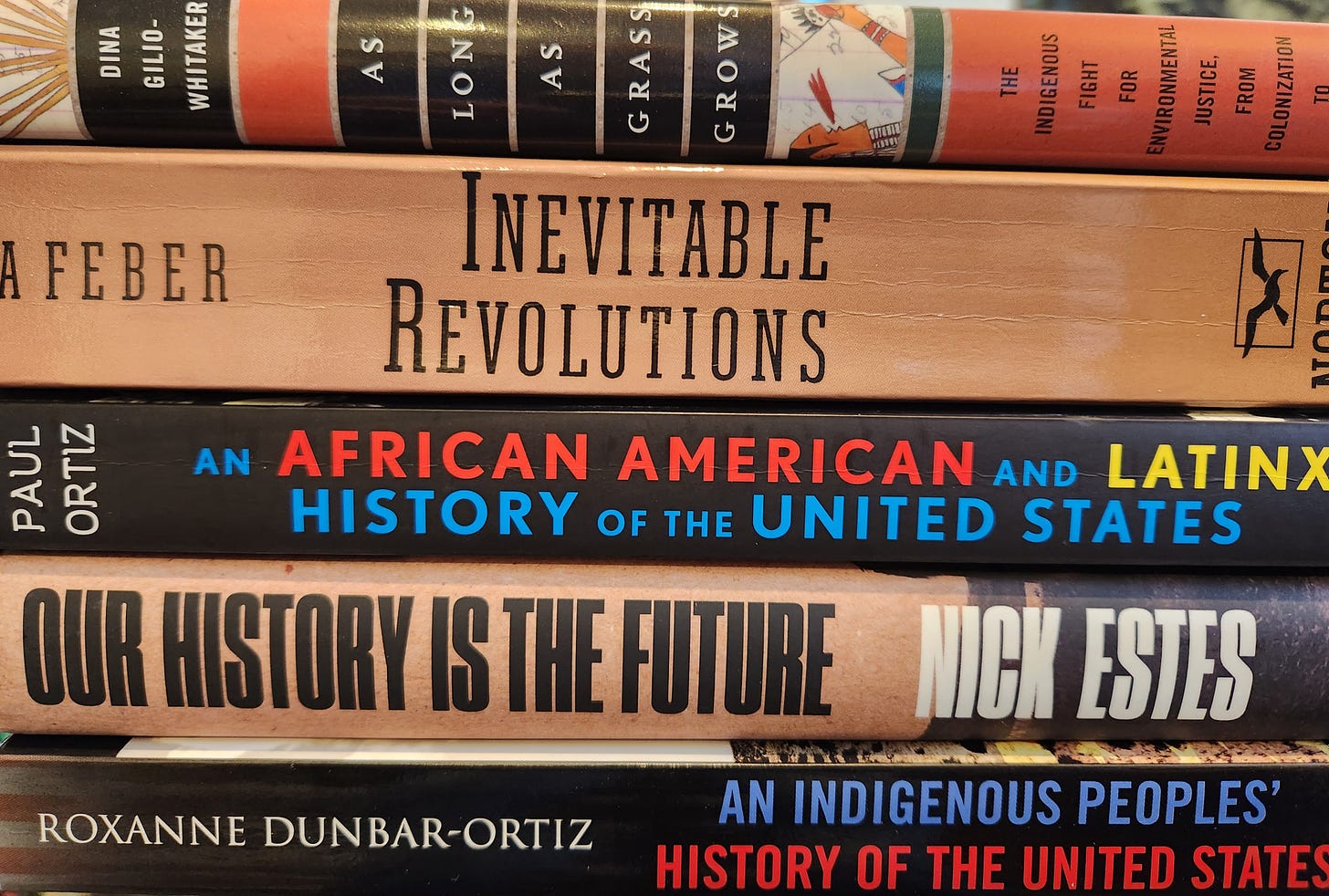

History to Inspire

History can provoke or inspire or catalyze, too, and many historians come to their work for just this purpose. This kind of writing shakes your worldview – sometimes as a challenge, sometimes as a reinforcement – to bolster a way of seeing. Inspiration can come from anywhere if there is fertile ground, but most often this approach emerges when it connects to social or political causes.

Sometimes this approach connects to what has been called a usable past. This expansive term incorporates many possibilities, but most commonly, I think about a usable past in the context of individuals and groups who have largely remained outside the canons of written history. Learning about the lives of those often hidden not only improves our understanding of past worlds but also can inspire or catalyze action today. Knowing strategies deployed to prevent voting in 1963, for example, might prompt you to act to ensure voting rights are protected in 2023. Every generation offers ample opportunities for the past and present to interact and inspire work to right wrongs and make the world a little better.

History to Reveal?

I have long thought about my writing but never more so than the last year. What is it that I hope my writing does or might do if I keep working at it? Inform? Certainly. Intervene? A little, but not so much. Doing so requires orienting everything in the process toward ends that feel too narrow to me now for an audience that seems increasingly foreign. Entertain? Sure, I hope to elicit some emotional reaction. But I’m not sure I’m an entertainer by inclination and there’s all that skepticism I’ve held onto for so long. Inspire? That’d be great, but (as above) I’m not sure I inspire naturally. However, I feel my writing often comes from a position as Citizen first, so if the work is a useful reminder to act as a citizen, I’d be pleased.

But lately, one of the things I think I want my writing to do is to reveal. “Reveal” blends both the purpose of the past – and writing about it – with a writing style.4 “Reveal” can be a close cousin to inform. Writing history that reveals something unknown to the reader is another way of teaching them, right? Sometimes it can be something readers simply haven’t encountered; sometimes it can be something that is so obscure that few people have ever learned it; sometimes it be can show a new way to look at old things. All these ways reveal the past. And I take satisfaction in sharing them.

But it is the style that I want to draw attention to now. To truly reveal something to the reader is to ask them to join in with the discovery and wonder that is the great joy I feel with I dive into a landscape or into archives or words and images from decades ago.

I could preach. Or insist. I could browbeat. Or lambaste. Then, my audience, by gum, would believe what I believe about the National Environmental Policy Act or the beauty of a landscape or what have you. But this is not my way temperamentally or by training. Instead, I want bring the past and places alive, tease out their meanings, show you how I see it and why. I hope that allows you to consider and engage it on your own terms and experiences with your own values and sensibilities. I hope this opens up the past and the landscape so that you might appreciate something new.5

Other Ways

Surely there are other actions historians consider when putting words to screens. Feel free to share them in the comments below.

Final Words

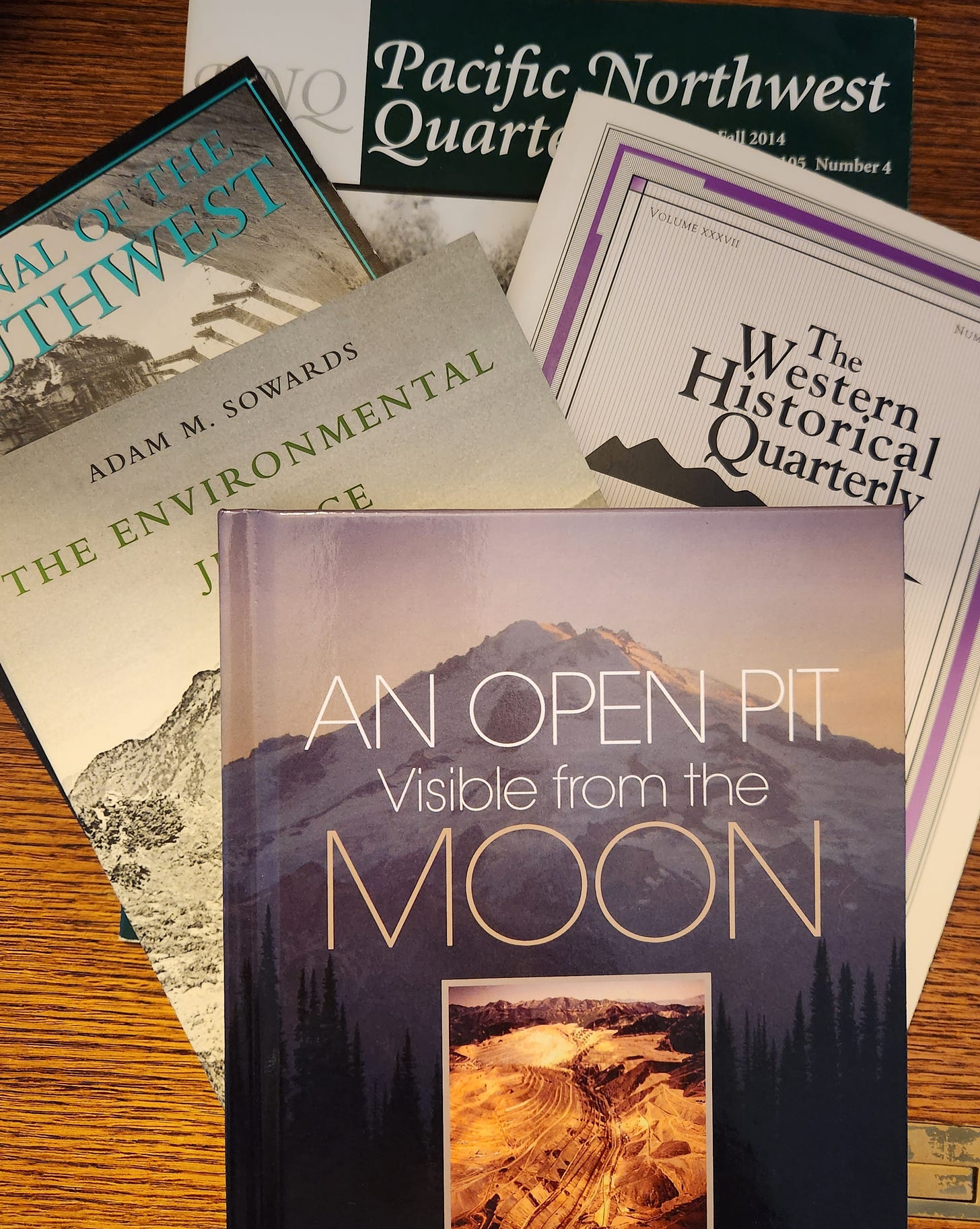

I’m not sure I’ve ever mused so much about the purpose of history, so I have no single writing to direct you to for further reading. But you could sample any of my writing on my website to see me attempting to teach, intervene, entertain, inspire, or reveal.

As always, you can find my books and books where some of my work is included at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

The Classroom will be in session next week. I have in my sights something related to policy concerning waterfowl, which are a ubiquitous presence in my life in winter. I know nothing about this policy context and intend to rectify this before next week.

Stay tuned and please consider sharing Taking Bearings with people who might enjoy it.

This list is certainly not exhaustive and undoubtedly idiosyncratic.

Interestingly, when I went to the author's website, the first blurb about the book in question came from … Entertainment Weekly, a sign if there ever was one!

I want to emphasize that there is nothing inherent in this type of writing that leads to such bad actors.

Maybe. This is a new thought I’m still working through. Check back later to see how I’m thinking about it!

By openly stating this, I’m inviting accountability to teach less and reveal more.

Early on, I read Barbara Tuchman's "A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century." Totally threw me, because she was such a good storyteller, such a solid writer, cover to cover, yet tightly beholden to the facts. It was a history written from the rabble's point of view. Soon, I read Howard Zinn's "The People's History of the United States" and found a compadre in the modern world. Now, I read Southwest archaeology which, because of writers like David Stuart and Steven Lekson, has become a narrative history rather than a series of scientific observations. And, now, when I have the all-too-infrequent chances to talk about a history, I always go to the ground floor, to the farmer, to the mill worker, and how their survival was what all was built upon. Today's "farmer" is the entrepreneur, upon which Amazon, Apple, Microsoft and their ilk are built upon. History tells us that the elite don't fully appreciate the efforts and thinking and foresight of those who have to "till the land" to make their way. And, it is their downfall. Thanks for your take on all this.