The Wild Card week for my newsletters offers me too much freedom sometimes, and I don’t always have a handle on what I want to write. But I’ve been thinking about the different ways history is written (and read) and wanted to explore that. Then, I saw a few newsletters and dozens of magazines and websites offering end-of-year book recommendations, and I thought I might be able to pull off a hybrid newsletter. Let’s see how it goes. Read on!

Types of History

I’m a voracious reader, and my reading crosses many genres. History is prominent among them. But in recent years, I’ve noticed that I consume less and less academic history, which had long been a mainstay. History is found in a variety of other forms, far more popular than what historians are typically trained to write.

I suspect many readers don’t consciously pay a lot of attention to these varieties, even if they do have preferences. I didn’t used to pay much attention myself, but as I’ve expanded my own writing repertoire, I’ve become more cognizant of these variations.

Below, I’m going to briefly describe a handful of books I read this year that connects to some of the themes that Taking Bearings tackles. I liked each book; I’d recommend them. But I’m more interested here in describing the books as a type of historical writing than in offering a detailed summary or recommendation.

The Novelist as Historian

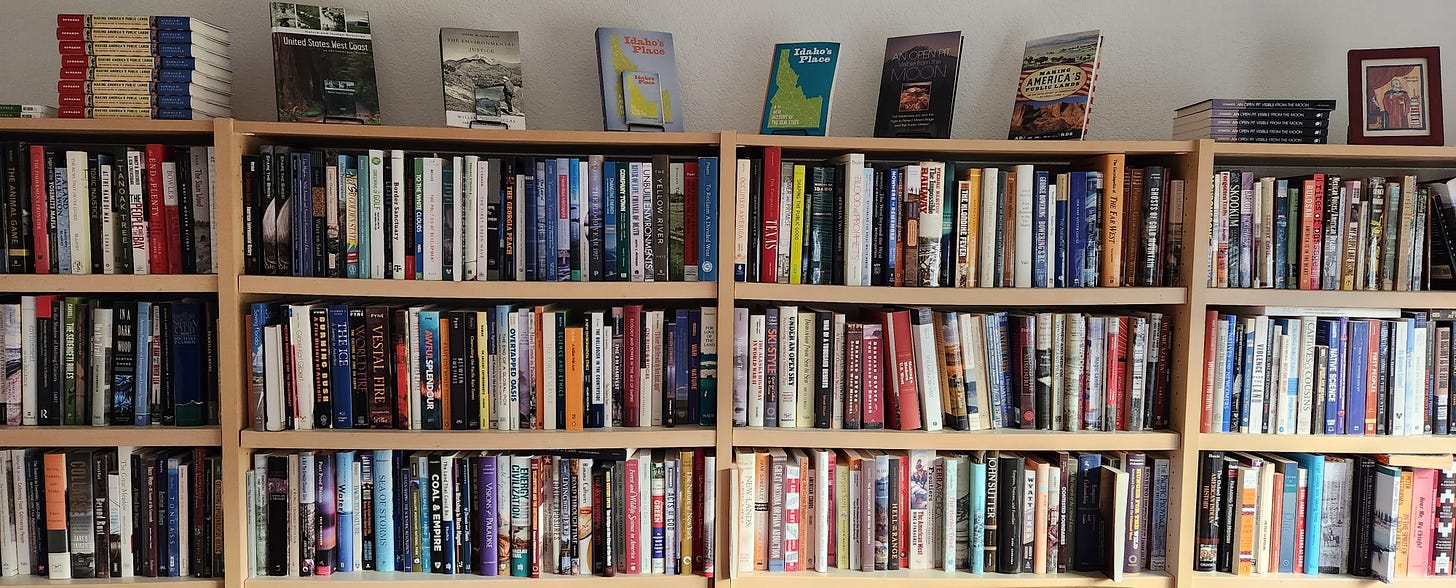

I encountered Wallace Stegner first as a novelist, and he remains best known for his fiction. However, Stegner also was a noted essayist and wrote several histories. His most famous is probably his biography of John Wesley Powell called Beyond the Hundredth Meridian. This year, I completed Mormon Country, a historical portrait mainly of Utah that presents an indelible image of the region.

Mormon Country was published in 1942, when Stegner was barely in his 30s. Stegner grew up, partly, in Utah and knew the state intimately, but not as a Latter-day Saint insider. His method and sources remain obscure – no author’s note, no bibliography. But what exists in abundance is affection – for the people and place. And that carries the book a long way.

Some novelists, when they turn to history, produce heart-pounding narratives with beautifully-rendered scenes dripping in metaphoric language. Mormon Country includes some of the latter but only bursts of the former. More common, the book is a series of impressions, both historical and contemporary. And Stegner presents them with confidence, an assuredness that I find common in books of that vintage but much less so today.

This approach makes for seamless histories that my training in graduate school taught me to be skeptical of. Those generalizations tend to mask diversity (of time, space, and cultures) but make for brisk writing. When I could suspend my critical training, I could sense that Stegner captured an essence of Mormon Country, because of the confidence of his tone. But I wondered where that confidence came from. His novelist sensibilities? His position in society? His past residence and familiarity? His uncited research? The zeitgeist?

This kind of work, with its easy pronouncements and breezy conclusions, fixes an image of a place (or a person) in the reader’s mind so much more powerfully than the sort of nuanced, over-cited work that academics are so notorious for. Yet, I’m not sure the conclusions or approach would stand today.

The Journalist as Historian (and Character)

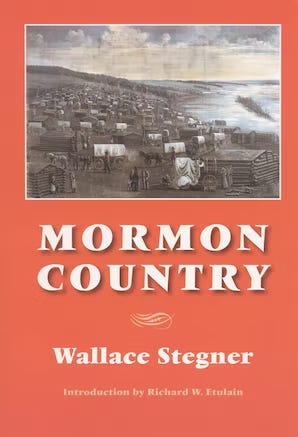

Let’s stick with Utah for another moment. One of my favorite books of the year was Jonathan Thompson’s Sagebrush Empire. Thompson – whose newsletter

is worth following for western environmental stories – tells the history of public lands through the prism of a single Utah locale, San Juan County. Momentous events occurred there, so it is an effective strategy. Many books purport to show how this small thing reveals the entire universe. Thompson makes slightly less grand claims, but carries them through. San Juan County does unlock lots of western history, but only because Thompson wields the keys well.Sagebrush Empire includes two things I enjoy more and more, when done well and when appropriate. First, Thompson includes himself in the book. This rhetorical strategy brings immediacy to the book and weaves a personal story through the landscape’s history. Done poorly, this approach can be self-indulgent and will often irritate me. That’s not the case with Thompson. He’s on the ground and conveys the scenes in ways that bolster the historical narrative and thread nicely through the book. Second, Thompson links the past to the present – obviously, one of my go-to rhetorical moves. Nothing emerges out of nowhere, so I always appreciate those writers who link up today’s issues with their past roots. This can often be done in facile ways, but Thompson is careful with his craft.

So Sagebrush Empire hits me in a sweet spot: Thompson demonstrates that the past influences the present and that our personal experiences bring alive past and present. As a young idealist, I might have imagined something like “pure” history existed: walled off from the person writing it or the time it was produced in and valuable only for its own sake. Thompson, thankfully, gets dirt on his writing hands and shows the lie to that idea.

The Journalist as Historical Polemicist

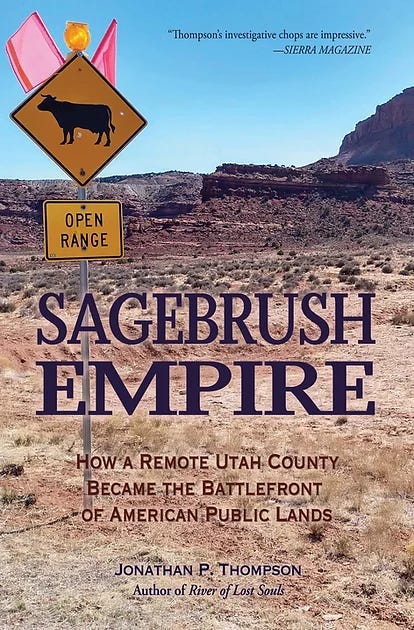

I fear I’m on dangerous ground with this label with a risk of misunderstanding, because “polemicist” to many connotes negativity. But a polemic is not inherently negative; it is simply an aggressive attack on an idea – or an aggressive defense of one. And Jacqueline Keeler’s Standoff is a powerful argument about sacred lands in the United States and deserves serious attention. Keeler is Diné/Ihanktonwan Dakota and a journalist who I doubt ever adopts “historian” as a professional identity. However, when you cover Indigenous and land issues, you cannot avoid history – and she doesn’t.

Standoff interrogates the stories of sacred lands held by Indigenous peoples who defended Standing Rock and what she calls the “Bundy Movement.” The divergent readings of the region’s past could hardly be more different. Polemics can be simplistic, but Keeler’s is not. It is wide-ranging in its historical analysis and its contemporary reporting. She shows, consistently and repeatedly, how the nation’s powerful favored the Bundy notion of sacred lands to Indigenous peoples’ – and all the consequences stemming from that. This is partly what explains the kid glove treatment applied at the Malheur occupation and the militarized response at Standing Rock, something Keeler brings into sharp relief.

The point of bringing Standoff into this list of books is to emphasize history as an argument, or a tool for and illustration of argument. But not (strictly) in the same sense as an academic argument. In that form, the argument focuses on the scholarly conversation almost exclusively: “My interpretation of this past thing contributes to the larger discussion of topic X, and my contribution is new and unique in these ways.” In Standoff Keeler uses history (and reporting) to advance a political (and moral) argument – as well as to convey an accurate report on how two standoffs over land by different groups of people revealed clear divisions in life in the United States. It’s a useful reminder of history’s power to clarify.

The Historian as, well, Historian

Bathsheba Demuth’s Floating Coast exemplifies the scholarly argument described just above. In a deep and often riveting environmental history of the Bering Strait, she engages scholars and theorists expertly – and better (much better, in fact) than most academic historians do. Yet, Demuth wears this learning lightly, which is a tricky balancing act. Academic historians are easily lulled into long, nuanced arguments with other academics. This is a lot of what graduate school entails; it can be hard to escape thinking almost solely about how some past event fits within the arguments historians and other academics have been having with each other for years (or generations).

What makes Floating Coast so good is that Demuth builds a history on this foundation, but she rarely lets readers see it. Let’s face it: if you haven’t already read those arguments, then knowing their ins and outs will likely get in the way and frustrate you. But scholars have important things to say and fitting those arguments together like puzzle pieces fleshes out the full picture of the past. But much of that work can be done in how the writer reads the evidence and presents the story. This is Demuth’s superpower, in my opinion. Floating Coast is deeply researched and engages important debates about history and economics and state power and more, but a reader who is merely interested in whaling or the area surrounding the Bering Strait can be invited on a historical tour with a knowledgeable guide.

Demuth can write in other ways, such as including herself like Thompson, but stays fairly traditional in this book. That is another point about history and historians: the varieties of genres and varieties of voices allow for experimentation in form, or the liberal use of one voice/form one time and a different one for different purposes. Demuth does this as well as anyone.

The Historian as Essayist

My final entry is probably my favorite book that I’ve included here and also might be the least fitting in this list. Vesper Flights by Helen Macdonald is an essay collection – and not one that is strictly historical. Macdonald is best known for H Is for Hawk, a book that is part historical, part personal, part natural history. In the book jacket, Macdonald is characterized as “writer, poet, illustrator and naturalist” and as an afterthought, “affiliated research scholar” in a history and philosophy of science department at Cambridge. So while, Vesper Flights is not a history; it is written by a scholar of history who does so much more.

Macdonald’s attention to the natural world is what draws me in. Vesper Flights, like H Is for Hawk, occurs mainly in the United Kingdom and in the present day, so these books do not hit my western past niche. Still, something about Macdonald’s writing strikes me as almost ideal. And I’ve come to think that working in history and among historians is not incidental; that it is, perhaps, the reason. I’m speculating, of course, and perhaps in a self-serving way, but I think the attention to detail historians (and other scholars, too) must focus on and the broad view of time they deal with as stock in trade make them nimbler on the page than many others who write.

There is, I think, a sensibility that Macdonald brings to essays that inspires me. It includes flitting in and out of time that, I suspect, was honed by historical thinking. It drifts and darts in ways far more organic than an outlined historical argument. What I wish for is more historians to turn to the essay as a genre, because Macdonald shows how a skilled historical thinker can turn writing into art and daily observations into meditations about how the world works, then and now. (See this essay as a sample of this at work.)

On Their Own Terms

Ruts are powerful. Thick historical narratives that include every detail of Napoleon’s life have a place. Dense academic analyses that qualify every nuance and exception have a place, too. Writing about the past can be a shapeshifting experience, because each time you sit down to write, you can do so with a different voice, a different genre, a different purpose. I think that considering those choices help us judge books on their own terms – something I haven’t always done. But part of being a critical reader of history is judging things on their own (historical) terms.

Final Words

Normally in this space I direct subscribers to other work I’ve written that connects to the post’s themes. This week, I don’t think I have a relevant reference. But, as always, you can find my books and books where some of my work is included at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

The Classroom is coming next week, and I’ve been thinking about the Southwest. I suspect I’ll spin out some history from that region – possibly related to some of my earliest historical research. Stay tuned!

In the meantime, thank you for reading and please consider sharing.

I appreciate how you classify these types of historical writing without creating a hierarchy of merit. Imagine if a field guide to birds claimed, for example, that birds of prey were more worthy of observation than shorebirds. No thanks. So, cheers for conveying the vitality of each of these ways of approaching historical writing.

What a wonderful look at how history is done, through presenting and commenting on these books. I think a lot about these elements going on in books of history, but more commonly social scientists'monographs. More to say, but another time I trust.