Reading Neglected Writers

In the mid-20th century, few writers packed the same punch as Bernard DeVoto. In 2022, only niche audiences know his name, much less have read his writings. Sometimes writers or other public figures fall out of favor and deserve to be forgotten or neglected, their voices not carrying across the decades. Yet, forgotten voices sometimes mean forgotten insights. And historians must and writers should read from other eras.

DeVoto made multiple reputations. A trilogy of western history book garnered contemporaneous attention and awards, but I’m interested in using The Library issue of Taking Bearings this week to focus on DeVoto’s role as an essayist or commentator. And, really, I aiming for a close examination of a single episode in a long career as a way of introducing DeVoto, showing his historical importance, and raising a question.

So far, I have always used all my newsletters during The Library rotation to focus on a single book, so I hope you’ll forgive this narrower aim this week. (The last one, Henry David Thoreau’s A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, took a bit too much out of me, if I’m being transparent!)

Read on!

DeVoto the Writer

Bernard DeVoto grew up in Ogden, Utah. Well-read and rebellious, DeVoto fit poorly in Utah and left the University of Utah in protest after a year, finishing up at Harvard. He never shook western dust from his shoes, though.

Always a lover of books, DeVoto taught English at Northwestern University and then moved on to Harvard as a part-time instructor while he wrote and edited articles and books, fiction and history. Often insecure professionally and financially (not to mention psychologically), DeVoto scrambled to put together a career, an approach that gave him a tenacious edge.

On the strength of an outstanding, incisive essay in 1934, “The West: A Plundered Province,” Harper’s gave DeVoto a slot with its monthly column, “Easy Chair,” something that began in 1851 and continues today.

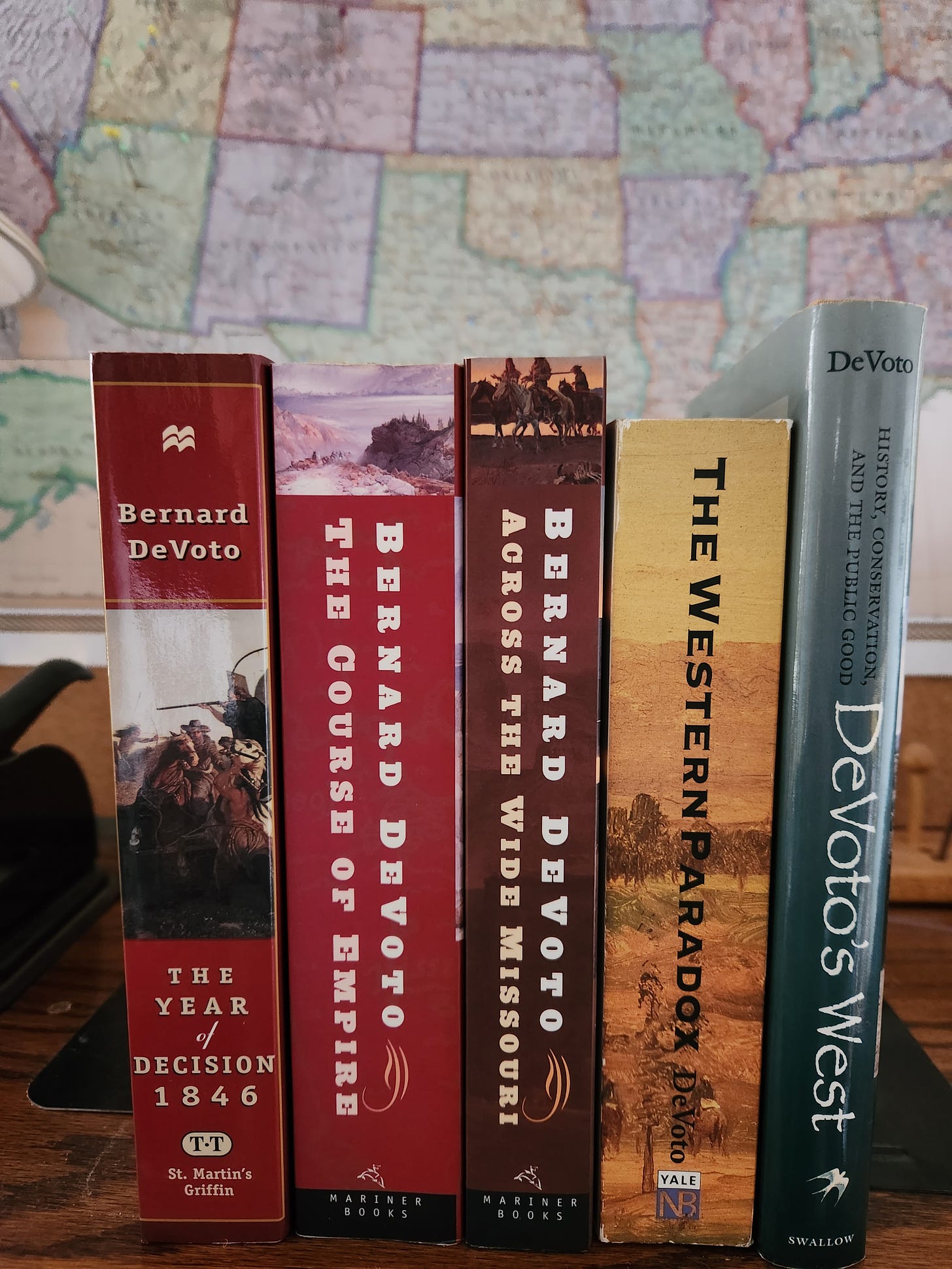

DeVoto did yeoman service by making some of Mark Twain’s work and the Lewis and Clark journals more readily available in new published editions. But his book fame came through a trilogy books on western history–real doorstoppers–The Year of Decision: 1846 (published in 1943); Across the Wide Missouri (published in 1947 and winner of the Pulitzer Prize in History), and The Course of Empire (published in 1952 and winner of the National Book Award for Nonfiction).

Wallace Stegner, a renowned western writer and conservationist (and friend of DeVoto), described the style that DeVoto achieved with the first of the trilogy:

When he applied the methods of impressionistic fiction to history, mounting upon the scrupulous gatherer of facts the storyteller skilled in mass entertainment; and when he mounted upon those, like an acrobat on the shoulders of two fellow acrobats, the social analyst and controversialist and editorial thinker of The Easy Chair, he had a combination that might look unstable and even self-contradictory, but that worked.

In simpler terms, DeVoto could tell a story with strict facts and drama arranged to highlight them, infused with social criticism and thick with opinion all his own. Not all historians appreciated it. But the public and many writers awarded him high marks.

What interests me more, at least for now, is how he used his “Easy Chair” column in Harper’s using his sharp wit, incisive thinking, and quick pen together to change conservation history.

A Plot Pursued

DeVoto was working on the final book in his trilogy, The Course of Empire and needed to see the West’s landscape, especially the path of Lewis and Clark. So, he and his family took a classic western road trip. Besides seeing magnificent scenery along the road, much of it protected by some federal conservation status, DeVoto learned of a plan hatched by stockgrowers and their congressional supporters. In This America of Ours: Bernard and Avis DeVoto and the Forgotten Fight to Save the Wild, a new dual biography of Bernard and his wife Avis, Nate Schweber tells this important story expertly.

DeVoto overheard a drunk cowboy in Miles City, Montana, talking about a plot to weaken the Forest Service and National Park Service. DeVoto kept listening and inquiring of writers and working conservationists as he looped through the West. The picture gradually came into focus.

The largest stock and wool interests pushed their best advocate in the Senate, the corrupt Nevada Democrat Pat McCarran, to advance legislation that would transfer all the public lands controlled by the Bureau of Land Management–some 146 million acres–to state control where it would be sold. This plan was a prelude to McCarran’s dream to strip the Forest Service of any land where grazing might occur.

This scheme would undermine the entire public land system and assault conservation writ large.

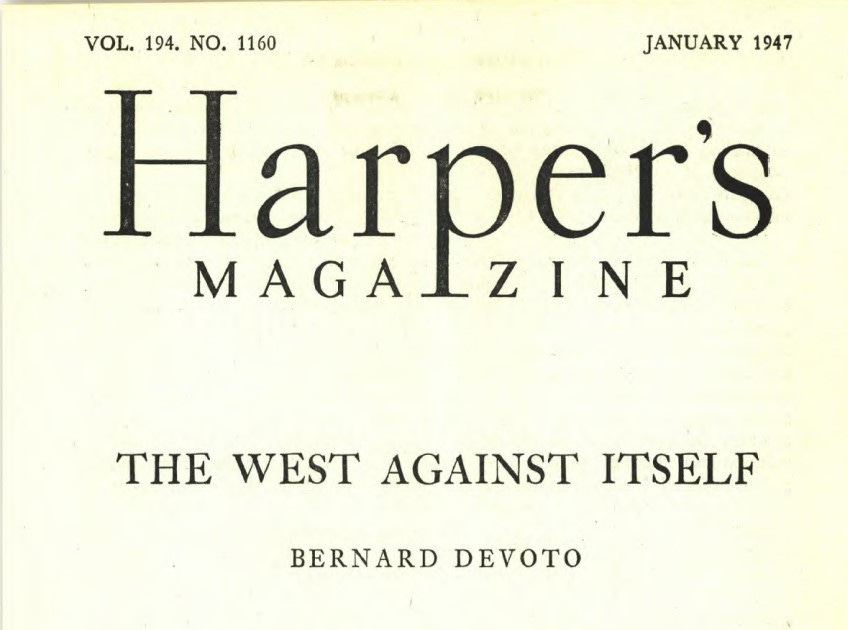

“The West Against Itself”

DeVoto needed a double-length article, not his typical column, to break the story in Harper’s in January 1947. “The West Against Itself” was the result. In several ways, the essay echoes the themes he first introduced in Harper’s in his 1934 “plundered province” article. Forces beyond the West exploited its natural resources for profits that rarely benefited westerners and left behind ransacked lands and waters. Here’s how he put it in “The West Against Itself”:

The East has always held a mortgage on the permanent West, channeling its wealth eastward, maintaining it in a debtor status, and confining its economic function to that of a mercantilist province.

DeVoto deplored these conditions, which he had witnessed growing up in Utah. In his 1947 piece, he began with a history lesson of one exploiter after another–fur trader, farmer, miner, oilman, rancher, and logger swoop in and take natural bounty, often violating existing laws and serving corporations and investors east of the Mississippi River. The colonial system–no doubt true and exaggerated by DeVoto’s pen–generated resentment in the West. But DeVoto believed the New Deal put the West on the road to sustainable development, an end to this colonial exploitation where the region might finally control its own economy and destiny.

DeVoto cited conservation programs and rural electrification and dams and the like. All these measures rehabilitated the deteriorating range and built up a new economic foundation with federal assistance. DeVoto characterized the reaction:

The West greeted these measures characteristically: demanded more and more of them, demanding further government help in taking advantage of them, furiously denouncing the government for paternalism, and trying to avoid all regulation.

Or, more succinctly: “It shakes down to a platform: get out and give us more money.”

It took DeVoto more than half his article to depict the West in these historical (and rhetorical) terms. In the last third of “The West Against Itself” he details the plot, emphasizing, “This is your land we are talking about.”

DeVoto explained the McCarran legislative agenda that would eviscerate public lands, transferring them from the American public to a sliver of wealthy westerners and, as DeVoto put it, “end our sixty years of conservation of the national resources.” The writer, from the Harper’s perch, castigated McCarran most vociferously but refrained little from attacking other western politicians and the leaders of western stock organizations behind this ruse. Hence the title: there were westerners willing to sacrifice their region’s resources and its potential independence for a small group who was “hellbent on destroying the West.”

He closed his long article with the key to it all: “[T]he future of the West hinges on whether it can defend itself against itself.”

This did not end DeVoto’s role in illuminating the nefarious plot. By raising the issue in public–in an influential magazine–and by continuing to publish about the land grab, as DeVoto called it, he put McCarran and his allies on notice, and they had to slow down and scale back ambitions. An aroused public refused to accept a private assault on public lands.

Way with Words

Recall Stegner’s characterization of DeVoto’s history writing. Dramatic. Factual. Analytical. Controversial. These elements are all here. No one would confuse “The West Against Itself” for a short story or novel chapter—or an academic treatise—but he told a story nonetheless.

And what was he like as a storyteller here instead of on the canvas of his sprawling books? I imagine DeVoto wrapping one arm around a reader’s shoulder kindly explaining how things were and with the other arm gesticulating pointedly explaining how things ought to be. He inspired with his narrative persuasion. This was, I take Stegner to mean, DeVoto’s way with words.

Postscript: A Query

DeVoto played notable roles in other conservation battles in this era. He helped to organize the campaign against Echo Park Dam, which would have flooded part of Dinosaur National Monument at the Utah-Colorado border. He publicized attacks in Wyoming related to the Antiquities Act that I mentioned a couple weeks ago. And constantly, his eyes were open to exploiters of western land. I’ve been wondering casually if there is someone equivalent to DeVoto today.

To ask the question requires us to figure out how to place DeVoto. He wrote to a national audience. And although he had ecumenical tastes in his coverage, his best-known pieces surely are on the West—his native ground, although he left the West before he was an adult (not unlike William O. Douglas, who I’ve written about at length). And although these columns and campaigns certainly presented political choices, DeVoto did not function as an activist or simple partisan; he was—and always wanted to be—a writer.

I’m curious if you can think of figures today who function in some similar way. If not, I wonder if there are clear reasons why not. If you have ideas, I invite you to weigh in the Comments section; I’d like to hear your thoughts. And if you read Taking Bearings on the Substack App, it now has a Chat function and I’ll pose this question there, too, and see if that’s a good way to interact.

Sources

Two volumes have collected many of DeVoto’s conservation writings, and if you do not have library access to hard copies of old Harper’s issues, they are superb: Douglas Brinkley and Patricia Nelson Limerick, eds., The Western Paradox: A Conservation Reader; Edward K. Muller, ed., DeVoto’s West: History, Conservation, and the Public Good. As for biographies, I relied on two: Wallace Stegner, The Uneasy Chair: A Biography of Bernard DeVoto; and the newest one with Nate Schweber, This America of Ours: Bernard and Avis DeVoto and the Forgotten Fight to Save the Wild.

Final Words

Several years ago I read DeVoto’s conservation essays, and I noticed a relevance to the words seven decades after they’d been written. I published an opinion piece in High Country News available here. Later, I included him briefly in a column for the same magazine about national parks, available here.

As always, you can find my books and books where some of my work is included at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

The Wild Card is coming next week, and I’m a bit indecisive. I think I’ll be sharing something about writing history and how I do it, or why I do it, or what we can learn from it. Or something like that. Stay tuned.

In the meantime, thank you for reading and please consider sharing.

Great piece. Benny DeVoto was one of the most important writers of the west in the last century, and unfortunately one of the most forgotten. Most people know Wallace Stegner but have never read his mentor Benny DeVoto.

Always great to be reminded of Benny's contributions to a better understanding of the American west.