A few prefatory words (and an important Announcement)

I’m glad you have found Taking Bearings. If you are not already a subscriber, please sign up for a weekly issue. (My plan for the newsletter is outlined in The Inaugural Issue.)

If you know someone else who might enjoy this, please forward the email, share the link, post on social media. I’d love to increase the readership.

This week is The Library, and I've read for the first time the first book of an author I've long admired. Read on!

Announcement

The word has emerged that the platform I use to produce Taking Bearings will be shut down by the end of the year. Accordingly, I need to transfer the newsletter to another platform. Readers do not have to do anything. It is supposed to seamlessly transfer subscriber email addresses and the existing newsletter. In fact, the old issues are already posted elsewhere. I hope that there are no issues. If there are, I'll sort it all out. (I fear there's a chance you'll receive two newsletters today, but I hope not and am confident that won't happen again.)

Next week, you'll probably notice some format changes, as I try out the new platform. I think this may open up some new features, too. In advance, I thank you for your patience as I work to migrate Taking Bearings and iron out rough spots.

You can see it at its new address here.

Floating with Thoreau

Finding Thoreau

I learned enough in high school to do well enough in college, but I discovered from my college classmates that many of them had read more widely than I had. And so, I learned about Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) in college rather than in high school when many of my friends first encountered him.

Probably, I should thank my high school teachers for not making me read “On the Duty of Civil Disobedience” before I was old enough to vote. It's an inspiring essay, but I imagine that, if read too early, it could surface immature libertarian thinking in a 16-year-old with lines like this:

I heartily accept the motto,—"That government is best which governs least;" and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which I also believe,—"That government is best which governs not at all;" and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which they will have. Government is at best but an expedient; but most governments are usually, and all governments are sometimes, inexpedient.

I would like to think that the months between high school and college made a difference, for when I encountered Thoreau as a college student, the impact was significant

Walden more than “Civil Disobedience” turned on my mind. I understood a fraction of it, I’m sure. Thoreau scatters Walden—and everything he wrote really—with classical illusions and eastern philosophical insights and minute observations about the natural world. Often these appear on the same page.

Thoreau can be exhausting to read. He can also be exhilarating to read. Not that many years ago, I discovered an essay of his that was new to me called “Huckleberries.” It was his last, and I love it. I taught it several times when I was still in the classroom. I wrote an essay in which it was a centerpiece. It opens my most recent book. Thoreau and huckleberries hit my sweet spot. The natural world becomes in his hands a field to explore the deepest secrets of the universe

Brief Biography

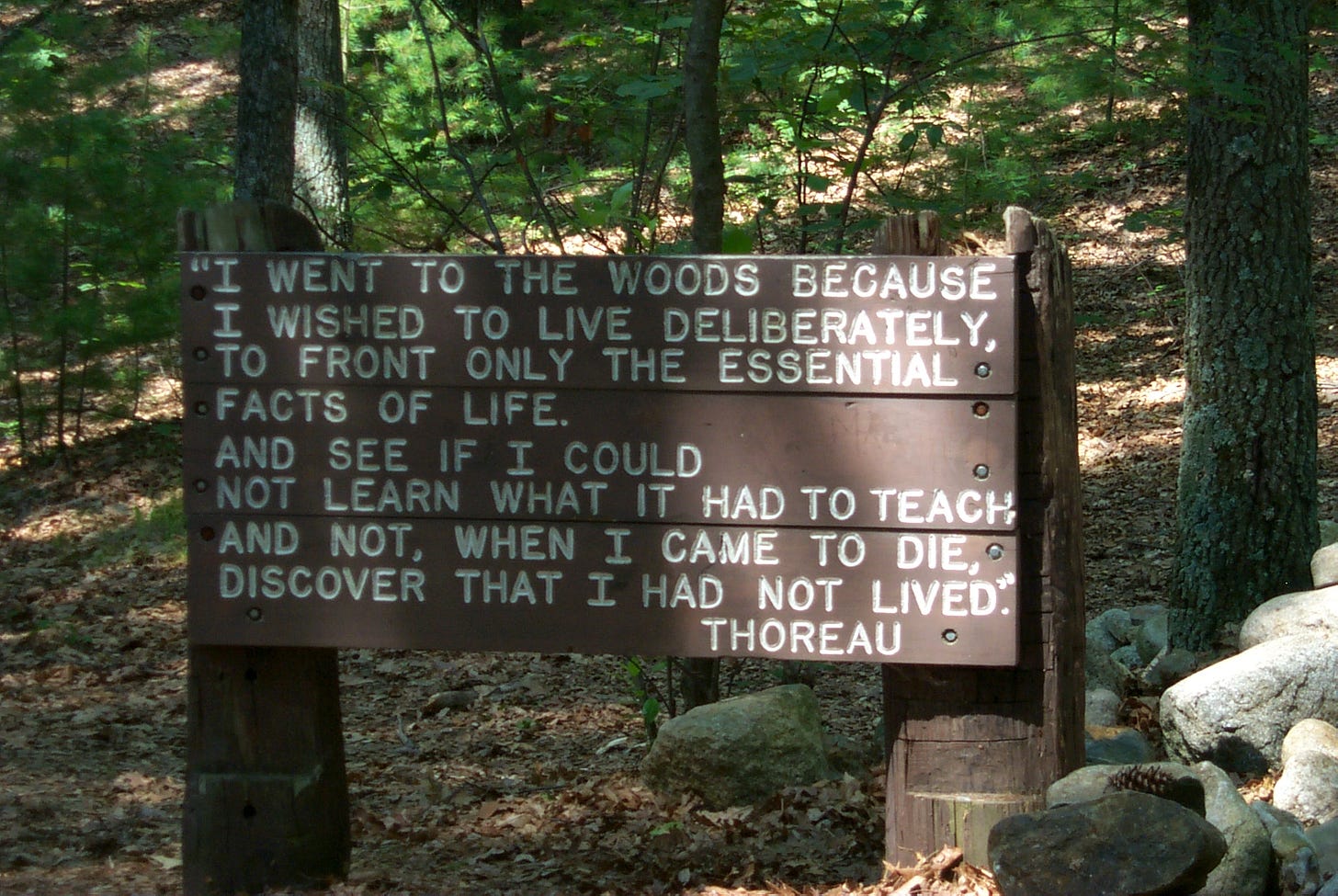

Perhaps Thoreau is new to you, so permit a brief introduction. He lived in Concord, Massachusetts, attended Harvard, and made high-quality pencils with his family. He lived within the intellectual (and physical) orbit of Ralph Waldo Emerson and the transcendentalists who declared literary and religious independence in the first half of the 19th century. Thoreau famously refused to pay his poll tax because the United States went to war with Mexico to extend slavery, so he ended up in the Concord jail overnight, which inspired “Civil Disobedience,” a reasoned essay that inspired Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. He spent two years in a small cabin at Walden Pond where he contemplated life and the meaning of nature. It is a masterwork of its type.

But Thoreau went to Walden Pond to write a different book, one I’d never read until now.

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers & Nature

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849) recounts a trip he took with his brother John in 1839 up and down the rivers. (It took two weeks, but the metaphor is nicer at one!)

Gradually the village murmur subsided and we seemed to be embarked on the placid current of our dreams, floating from past to future as silently as one awakes to fresh morning or evening thoughts.

One of the first things the Thoreau boys encountered were dams. After providing some fish taxonomy, Thoreau noted many fish were rare “on account of the dams.” Two centuries ago fish were blocked, and Thoreau worried, “Poor shad! Where is thy redress?”

Such remarks, coming from a time most of us have a hard time conceiving clearly, help remind us environmental changes are old and ongoing. And the search for moral redress crosses species boundaries.

Thoreau contained multitudes (apologies to Whitman), but what connects best for me are these sorts of environmental observations. For instance, I may share this Thoreau sentiment, “There is in my nature, methinks, a singular yearning toward all wildness.”

The Book's Meanders

Yet, Thoreau’s river book meanders through commentaries on books (“Read the best books first, or you may not have a chance to read them at all.”) and writing (“A perfectly healthy sentence, it is true, is extremely rare.”) and friendship (“In human intercourse the tragedy begins, not when there is misunderstanding about words, but when silence is not understood.”) and much more.

The tidbits of Thoreau’s words I’ve shared here are characteristic of part of his style. He could write easily in aphorisms.

“The works of man are everywhere swallowed up in the immensity of Nature.”

“We can never safely exceed the actual facts in our narratives.”

Etc.

But just as often, he could turn his prose this way and that, back on himself, before gushing forward with a torrent of references that skitter you across the globe and history. It can be as bewildering as some of the stretches of river the Thoreaus traveled through. Throughout the landscape he traveled through, the colonial history of violence lay barely concealed and he unearthed it and lodged it in his book. (He planned an “Indian book” someday, eventually filling 12 notebooks.) The travel narrative served to explore nature and history and philosophy, always rooted in firsthand observations.

In Thoreau’s day, rivers were highways in ways most of us do not experience now. He saw the land and the society that lived along rivers differently than we do zipping along in cars and over land in planes. The speed and more today makes travel something different, something less contemplative. For Thoreau, this journey with his brother forced deep personal reflection, especially as John died in January 1842, not even three years after the river adventure. A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, then, was a memorial to John, a weight that oppressed him during the decade it took to produce the book

Returns

For all its descriptions of landscapes and interesting literary and spiritual observations, Thoreau’s first book suffers from a common issue of first books: he tried to put everything in it for fear he would never write another. Oodles of poetry—his own and others’—are strewn within the pages. Digressions too numerous to list and too diffuse to characterize punctuate the pages. The result was a failed book. He paid to have it published, and it sold terribly. The printing costs kept him in debt for years. Thoreau reported earning only $15 from A Week.

Not much of a recommendation, is it? Nonetheless, I found A Week worthwhile. The nature writing is enough. The colonial history adds more. The writing advice contains gems. But mostly, to go with Thoreau along the Concord and Merrimack Rivers is to accompany one of the most unique minds produced in the United States. You don't have to agree with everything (or even understand everything) to benefit from seeing Thoreau at work.

At the end of the Thoreau brothers’ journey, they floated into Concord. Henry David and John jumped ashore and fastened the boat “to the wild apple-tree, whose stem still bore the mark which its chain had worn in the chafing of the spring freshets.”

And for me, returning to Thoreau found a worn spot in my mind where his influence still settles.

Sources

This issue relies on my reading of Thoreau's own writings, but I have also benefitted from Laura Dassow Walls' excellent biography, Henry David Thoreau: A Life

Closing Words

My essay that uses Thoreau's "Huckleberries" essay can be read here. In it, you'll also encounter some other thinkers who have influenced me and learn how I think of education.

Last week, I spoke about my latest book in Fort Collins and Provo. I had a great time. The lecture in Provo will be available to view on YouTube later, and I will share it here when it is ready.

Taking Bearings Next Week

My plan for next week is to take you a behind-the-scenes with an on-going project of mine. I hope you'll enjoy learning how things come together (or don't, as the case may be).

Until then, as always, thank you for reading. And see you next week on a new platform.