I recently read a marvelous novel that concludes in the American Southwest. (Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli, which I heartily recommend if you don’t require that books’ subjects uplift you.) And the book I’m working through for this newsletter’s next The Library issue similarly takes place in the Southwest. So my mind has been thinking about desert places and dry mountains, and that leads me to the research that launched my historian’s career. Read on!

The Lucky Way to Pick a Thesis Topic

Some people go to graduate school knowing exactly what they hope to research. In many fields, especially STEM, the project is defined not by the graduate student but by the sponsoring professor. I’m grateful for the freedom I found; I could choose whatever I wanted. But that has its own burdens.

I started my Master’s program at Arizona State University with the idea that I’d write an environmental history of somewhere in the West. Back in those days, before the field expanded to become more inclusive, common topics included studying a type of land use, and for much the West that included things like logging, ranching, mining, and farming. (The urban West did not excite me in the same way.)

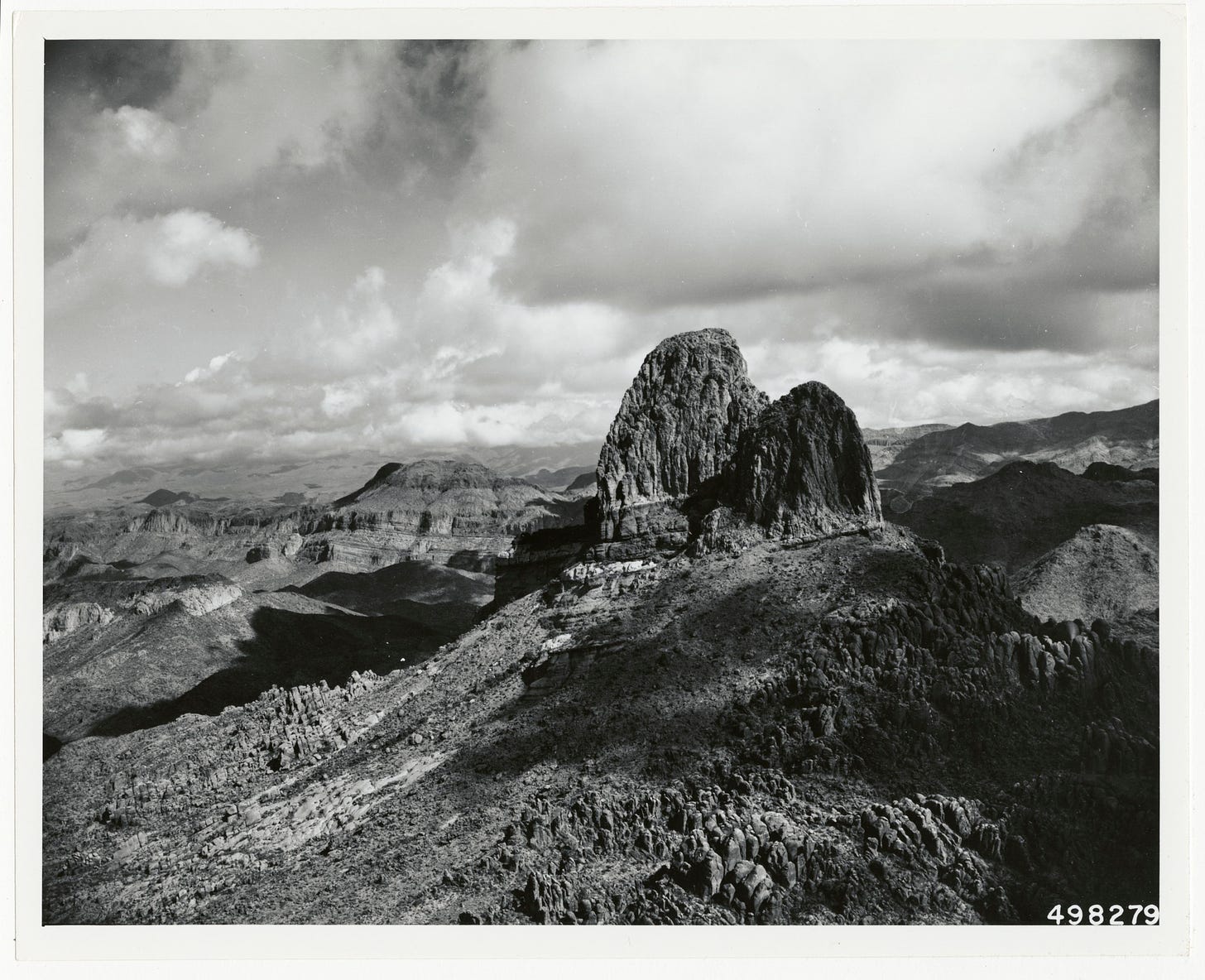

I figured studying something in Arizona made sense, logistically. I logged on to the library computer and searched terms like: Arizona, forests, grazing, mining, irrigation.1 What popped up the most was “Tonto National Forest,” a place northeast of Phoenix with some trees, some cattle, some mines, and some dams and reservoirs. I had my Master’s thesis topic.

It worked out well. But I think I got lucky with this “method.”

Findings

In fact, I got very lucky. The topic ended up being a rich one. On the one hand, I think the history I wrote followed a fairly common trajectory for scholarship in that day and age. But besides treading over well-defined paths, I found something new-ish, too.

Here, I want to highlight one part of this history that is widely applicable across the American West and one part of the history that remains underdeveloped with potential for an energetic scholar.

Protecting Forests and Watersheds

Pastoral economies expanded throughout the West in the late 19th century. Following the hoofprints of many thousands of cattle and sheep came a series of environmental calamities. Livestock grazing transformed western forests and rangelands, displacing existing populations and land practices. Overgrazed ranges encouraged erosion. Fire regimes were upended. Wildlife faced new threats and competitors. Not much looked the same once domestic overspread the landscape.

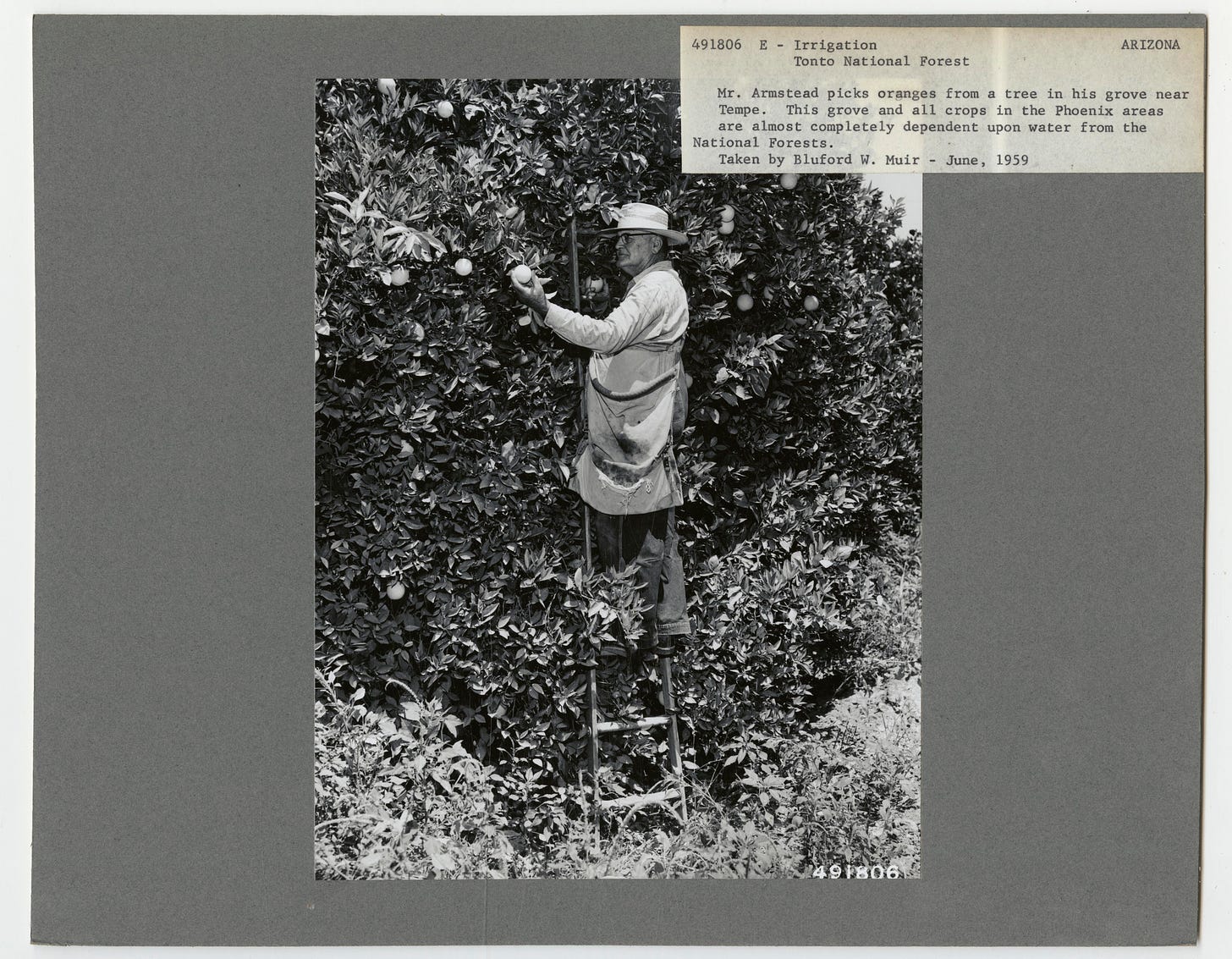

That was the partial context for the rise of the conservation movement (some of which I detailed here). For the West, the conservation of forests and the conservation of water proceeded hand in hand. In 1891, Congress gave the president the power to protect forests; in 1894, Congress passed the Carey Act, a gift to western states of a million acres to develop with irrigation. When the Carey Act largely, but not entirely, failed to produce many new communities of irrigated farms, Congress offered a new approach: the Reclamation Act of 1902, also known as the Newlands Act after its sponsor Francis Newlands. The symbolic power worked far beyond a politician’s name. The Newlands Act used federal money – and expertise – to construct dams and the larger irrigation apparatus to support farming in the arid West. (The money was supposed to be paid back. Sometimes, it was.)

In Arizona, conservationists worried about the problems caused by overgrazing. They also wanted to support the growing agricultural economy in Phoenix that required irrigation. In 1905, not by coincidence, Tonto National Forest was established and Roosevelt Dam was approved, the cornerstone of the Salt River Project funded by the Newlands Act. Protecting the forest and range as a watershed functioned in concert with developing the Salt and Verde Rivers. But while federal conservationists might have seen common cause in the ranges and the rivers, economic (and cultural) divisions emerged.

Farmers who lived downstream in the Salt River Valley became the favored party. In most areas of American life, farmers represented solid citizens who “settled” down and built permanent communities within recognizable property regimes. Ranchers certainly symbolized important things to Americans; the cowboy must be the most mythological figure in American history, or nearly so. But ranching seemed to produce less stable communities, while herders led or chased animals up and down the mountains relying on open range or, later, the national forests. Conservationists prioritized the irrigation downstream, aiming to restrict ranchers’ use of what became Tonto National Forest.

This completed part of the story I tried to tease out in that long-ago Master’s thesis: showing how ranching and farming were connected in this landscape with federal conservation both converging and diverging while linking forests and water tightly. This historical relationship certainly bore a familiarity to other watersheds. A significant percentage of the earliest national forests served as watersheds to urban communities, and the rivalries between ranchers and farmers over competing uses of resources struck a common rhythm, too.

Urban National Forests

The main historical narrative of the forest that I wrote is simple, and I can illustrate it using the famed conservationist Aldo Leopold.

Leopold worked in the Southwest Region for the US Forest Service. During a reconnaissance in Arizona, Leopold identified what he saw as the basic land-use history since white settlement:

“[W]hen the cattle came the grass went, the fires diminished, and erosion began.”2

Simple, but true enough.

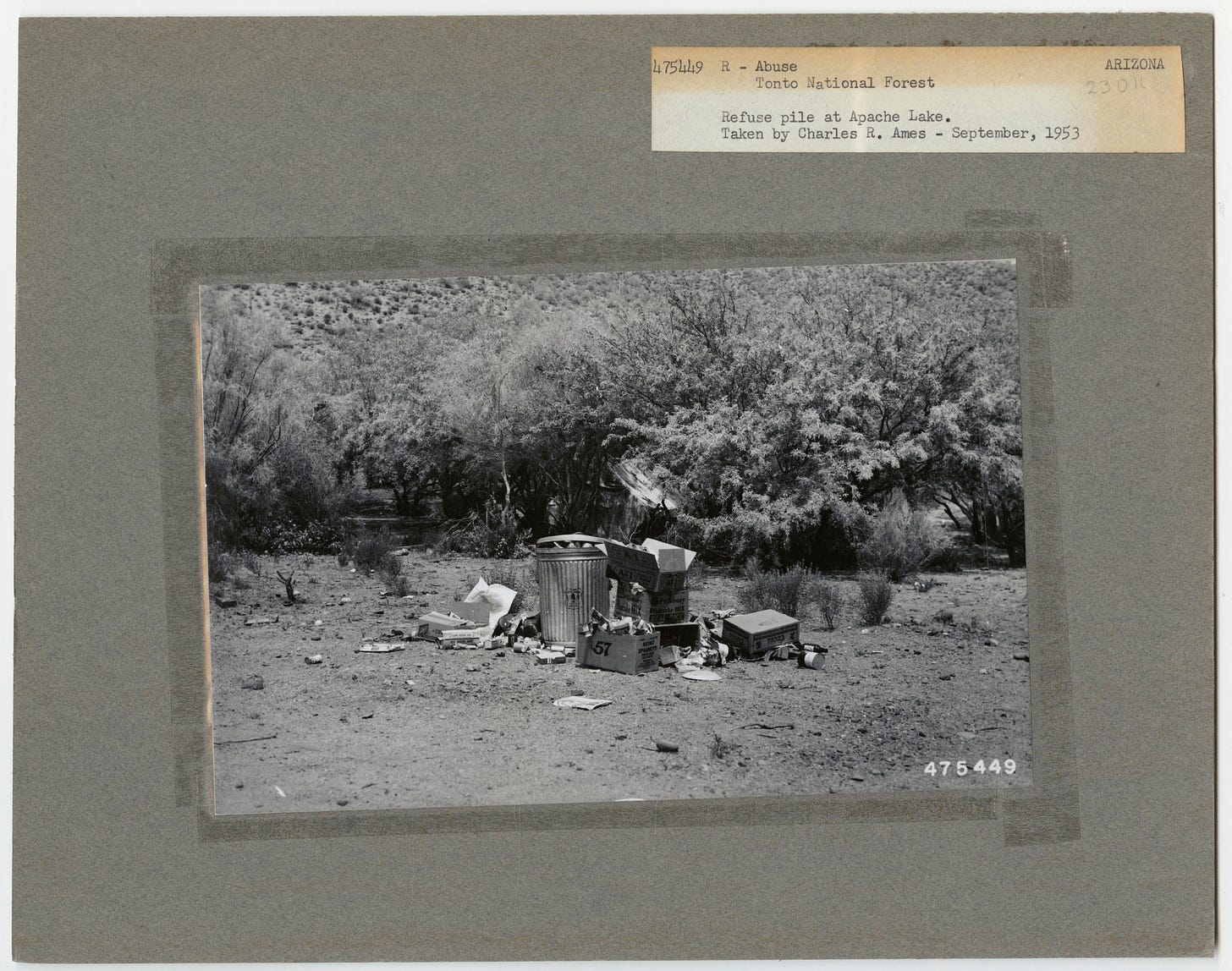

In my thesis, I argued that Tonto National Forest attempted to reverse those trends after the 1920s. That is, they tried to reduce the number of livestock so the grass could recover, slow or stop erosion, and reintroduce fire. Efforts at recovery lasted for a half-century or so. Around the 1980s, the forest administrators (if not local environmentalists) figured that finally they got livestock numbers aligned with range capacity. The irony, though, was that by then the forest’s main constituency was not ranchers or farmers but urban recreationists, primarily using the reservoirs but also hiking in various wilderness areas. I suspected then that the Forest Service probably was ill-prepared for this. An agency born during a conservation pulse that sought efficient management of resources might not have been prepared to deal with this dynamic or constituency.

At least that’s what I thought then. I think I was right. I also think the Forest Service has improved since the 1990s on this issue.

Later in my career, I began a project – never completed – that aimed to explore this dynamic in greater detail and a wider scale. In the 1990s, as I recall, the Forest Service became interested in what they called “urban national forests,” which were defined as forests located within 50 miles of metropolitan areas of a million or more. At the time I looked into these unique forests, I recall something like a dozen forests meeting this designation. Now, the agency cites more than 60 national forests. (I’m not sure why there is this discrepancy, but I suspect some changing definitions, along with population shifts.)

Urban national forests included many of the same resource and ecosystem issues as forests in rural places like Montana or South Dakota. But they also faced some unique challenges owing to the presence of larger populations. Most of those were recreational. Large urban populations taxed nearby national forests with legions of day hikers and backpackers and their impacts. The pressures of urban growth also presented national forests with an issue not as familiar as, say, grazing fees or timber sales. Pollution from urban industries impinged on natural conditions, too. A more diverse set of stakeholders also pressed the Forest Service on urban edges. On and on, the different issues mount.

As an issue of current land-use dilemmas, urban national forests offer an enticing topic. However, I wondered earlier – and still do – what a longer history of this relationship might reveal. What are the urban roots and links between national forests and cities? Obviously, watershed protection is one longstanding tie. Economic patterns could also be tracked. I remain convinced there are untold, essential historical roots that tie national forests with cities. I hope an enterprising history graduate student or some other author is hard at work on this.

Final Words

I published two articles based on my thesis. The first one describes the environmental degradation and initial conservation efforts can be found here. This is the first piece of scholarship I published.3 The second one that examines how foresters attempted to restore the landscape is available here. The latter piece earned the Bert Fireman Award from the Western History Association, my first award for writing history. I was earnest and careful back when these were published, but I am probably a more practiced writer now!

As always, you can find my books and books where some of my work is included at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

The Field Trip is coming next week, and I have a local spot I’m planning to visit. It’s new to me, but it has a history with some importance. Stay tuned.

In the meantime, thank you for reading and please consider sharing. And enjoy the holidays.

Note: I do not recommend this method; however, it worked not only this time but once more. I chose this topic virtually the same way.

Aldo Leopold, “The Virgin Southwest,” in The River of the Mother of God and Other Essays by Aldo Leopold, ed. by Susan L. Flader and J. Baird Callicott (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991), 179.

I wrote another piece earlier that appears in the book John Muir in Historical Perspective, but it was published the following year.

I know what you mean! When I started my dissertation almost nothing was digitized. It’s a totally new world!

Thanks for your kind words about my newsletter!

I loved the Lost Children Archive! Such gorgeous writing and such a powerful story. I loved learning a bit more about your research, and I especially enjoyed all those archival photos!