As I recall it, the first day of the environmental history class I took as a college junior — the class that set me off on my career path — included a discussion of national parks, something I’d never considered seriously. In some ways, I’ve been studying them ever since, and I continue to learn. How the parks have changed over time fascinates, and sometimes perplexes, me.

To understand them, I often rely on other scholars, but for The Library this week, I took a century-old book off my shelf, National Parks Portfolio (4th edition), by Robert Sterling Yard. I figured this book might reveal some insights about the parks when the National Park Service was not yet a decade old. Read on!

The Need and Purpose for National Parks Portfolio

Yellowstone became the first full-fledged national park in 1872, but the creation of the National Park Service (as I detailed here) did not happen until 1916. The principal thing the park system needed if it was going to thrive was visitors. National Parks Portfolio hoped to help.

Its first edition, published in that inaugural year, was provided to 275,000 American business, political, and educational leaders. Seventeen western railroads provided $43,000 to ensure the book scattered across influential paths. Railroads furnished this critical support to the early national parks, because they stood to benefit from tourist traffic.

The national parks were not well known in 1916, or 1925 when my fourth edition of the Portfolio appeared. Even the most famous parks — Yellowstone and Yosemite — only included a few features popularly known. The Portfolio aimed to share these places to increase the public’s knowledge.

Besides the relative anonymity of these parks, national parks were a new idea, and their boosters needed to educate the public about not only the parks’ features but what the parks were for.

I paged through this book and found many things I both expected and didn’t.

Front Matter

The book begins with prefatory remarks from important government administrators who wished to convey particular lessons about national parks.

Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work wrote the Introduction in which he announced a cyclical view of history. The most recent cycle offered a reaction against the “artificial life dependent on the indoors” that Americans now lived. Instead, “we are turning back to the simpler pleasures found in the woods in contact with nature,” such as that provided in national parks. Besides providing system-wide opportunities for outdoor recreation, the National Park Service offered serious educational functions, the parks being “natural laboratories for the study of science.” Such study would bring children closer to God, according to Work in the kind of religious sentiment no longer common in government publications.

The National Park Service director, Stephen T. Mather, included a short note, too. Sounding similar tones, Mather called the parks “the most inspiring playgrounds and the best equipped natural schools in the world” with an “incalculable value” for the economy. The parks were individually distinct and revelatory as an entire system.

Together, these short documents helped set expectations for the volume. And those expectations were high. Visitors would be looking forward to amazing things in the parks based on the preview offered in National Parks Portfolio.

Yard and the Book’s Mission

Yard had worked in journalism, but for this task he amounted to a publicist for the parks. He developed a set of high standards for parks and, eventually, helped found the Wilderness Society in part out of dissatisfaction with what he saw as falling standards. But for this fourth edition, he remained an enthusiastic supporter of the park vision.1

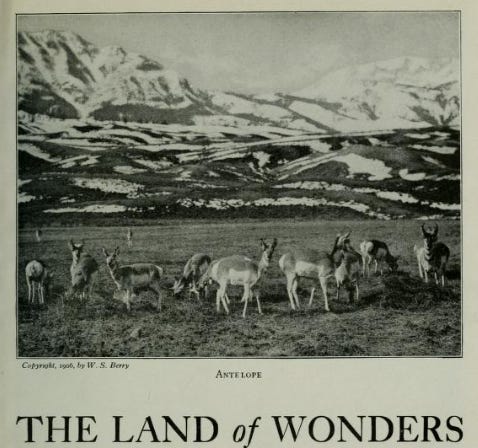

Yard developed the book through words and images, heavy on the images. The book is packed with photographs with short informational vignettes about all the parks and national monuments between images of stunning natural features. The first 85% of the book includes relatively long features on the major individual parks. The last 15% contains very brief paragraphs about lesser parks and monuments. Taken as a whole, Yard effectively sampled the system and enticed visitors.

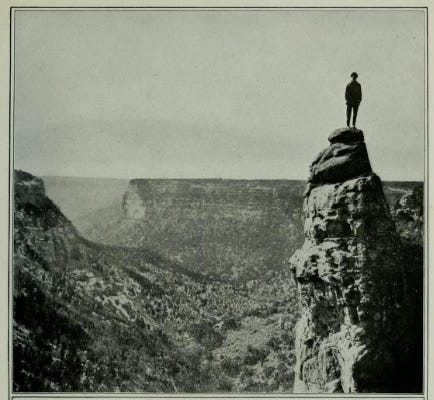

Yard and other park advocates had balance two things: unique and sublime scenery and ease of access. That is, they needed to show the unusual natural features the parks highlighted: the rugged canyons, astounding geysers, majestic glaciers, abundant wildlife. None of those was easy to find in the cities where Americans increasingly lived. And they had to demonstrate that roads were easy to navigate with lovely hotels and comfortable camps along the way that put visitors into the heart of these rugged landscapes.

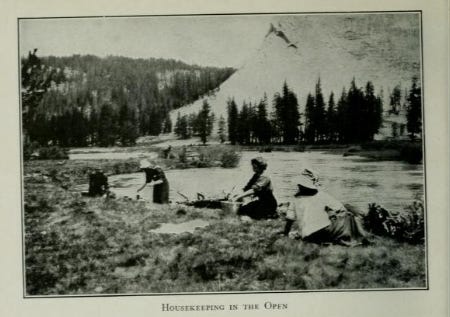

To emphasize the kind of accessibility Yard was after, many photographs showed roads and others put women into the backcountry doing everything from “housekeeping” to gazing into a crevasse.

Getting people to the parks was only part of the mission. Getting them to stay was the other. “Stay with the wilderness and it will repay you a thousandfold,” Yard wrote. This sentiment pervaded the book, an encouragement to stay in the parks not just overnight or for a couple days but weeks on end to learn the lessons nature could teach if visitors could afford to be patient and settle in.

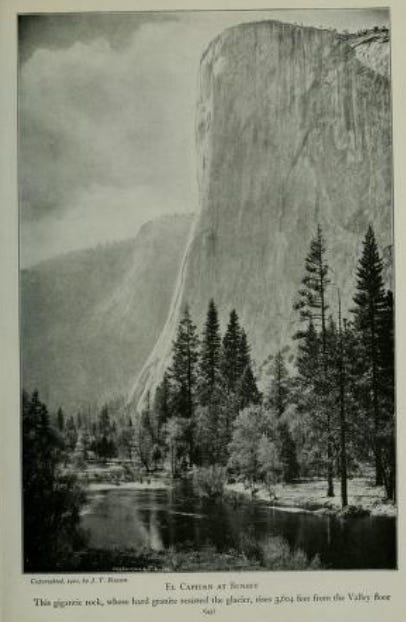

For by settling in, visitors would learn from nature’s laboratories. And if visitors did not want to study, they could still appreciate nature’s marvels. A paragraph from the section on Yosemite exemplified the type of enticing nature writing used to paint natural portraits of place:

Summer in the Yosemite is unreal. The Valley, with its foaming falls dissolving into mists, its calm forests hiding the singing river, its enormous granites peaked and domed against the sky, its inspiring silence haunted by distant water, suggests a dream. One has a sense of fairyland and the awe of infinity.

Who wouldn’t want to visit a fairyland with foaming falls?

What Surprised Me

National Parks Portfolio provided just the glimpse I wanted. It confirmed what I knew: that the National Park Service wanted visitors to come to spectacular parks where nature would inspire them as Americans and where the agency worked hard to make the visit relatively easy given necessarily rustic conditions.2

But I was surprised by some things. Traditional accounts of the national park movement argue that concern about “environment” started emerging in the 1930s. Scenery-only dominated early. Only later did something we might call ecology offer itself as a rationale for parks. National Parks Portfolio does not revise that interpretation. However, the emphasis on studying nature suggests the direction parks might take — toward something more strongly ecological. Yard also used “watershed” early in the book, indicating future ways of conceiving of these landscapes organized around ecological processes rather than simply scenic areas.3

Historians know that primary sources — those written at the time of the events we study — hold the keys to the past. It is often handier to read scholars, but when we return to the primary sources, we can discover clues that can deepen and alter our understanding.

Closing Words

Relevant Reruns

A couple months ago, I wrote several newsletters in a row about national parks. Check those out, starting here. And my very first contribution for The Library was about Yellowstone in a book published around the time of National Parks Portfolio; you can find it here. Finally, this essay connects to some of the paradoxes at root in national parks’ founding.

New Writing

A new story of mine is up about some of the changes seed farmers are facing as climate changes. Read it here.

Also, a new interview will be posted this weekend for paid subscribers. Upgrade now if you want full access.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

The Wild Card comes around next week. Stay tuned!

My favorite account of Yard is Paul S. Sutter, Driven Wild: How the Fight Against Automobiles Launched the Modern Wilderness Movement (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), 100-41.

It also confirmed that the park service in its earliest years paid little attention to the racial or class politics involved in the parks, especially the recent removal of local tribes from these landscapes.

The fact that some of the photos came from US Reclamation Service might also have meant flashing warning lights for some of those watersheds.