Before I start this week’s newsletter, please allow me to make an appeal and an offer.

August will mark two years of Taking Bearings, two years of weekly thoughts and lessons about place, history, and writing. I am hoping to increase subscribers and would be grateful if you shared this newsletter with a friend or family member you think would enjoy it. I’ve turned on a referral program. After four referrals, you will be comped free access to paid content for a month (and the rewards increase with more referrals).

I’m also asking that current free subscribers consider upgrading to the paid option. To celebrate the pending two-year anniversary, throughout July I will offer a discounted subscription rate.

Thank you for your consideration. ~Adam

Tomorrow is the Fourth of July, so I am thinking about American things. For me, that includes the public land system, including national parks. The parks stand as among the most powerful symbols for all of American history—and that includes difficult, complicated, and unpleasant parts of the nation’s story. I think I’ll have more to say on that another week. For The Classroom this week, I want to share a bit about the origins of the parks. Read on!

Originalism in the Parks

In certain circles, I’ve heard lately, we are supposed to understand history through the original meaning of old texts. “Originalism,” some proponents call it. Historians like to look at old texts, too, and we do a lot of work to try to read them in appropriate contexts.

Let’s dig into to some “original” language about national parks.

Yosemite (1864)

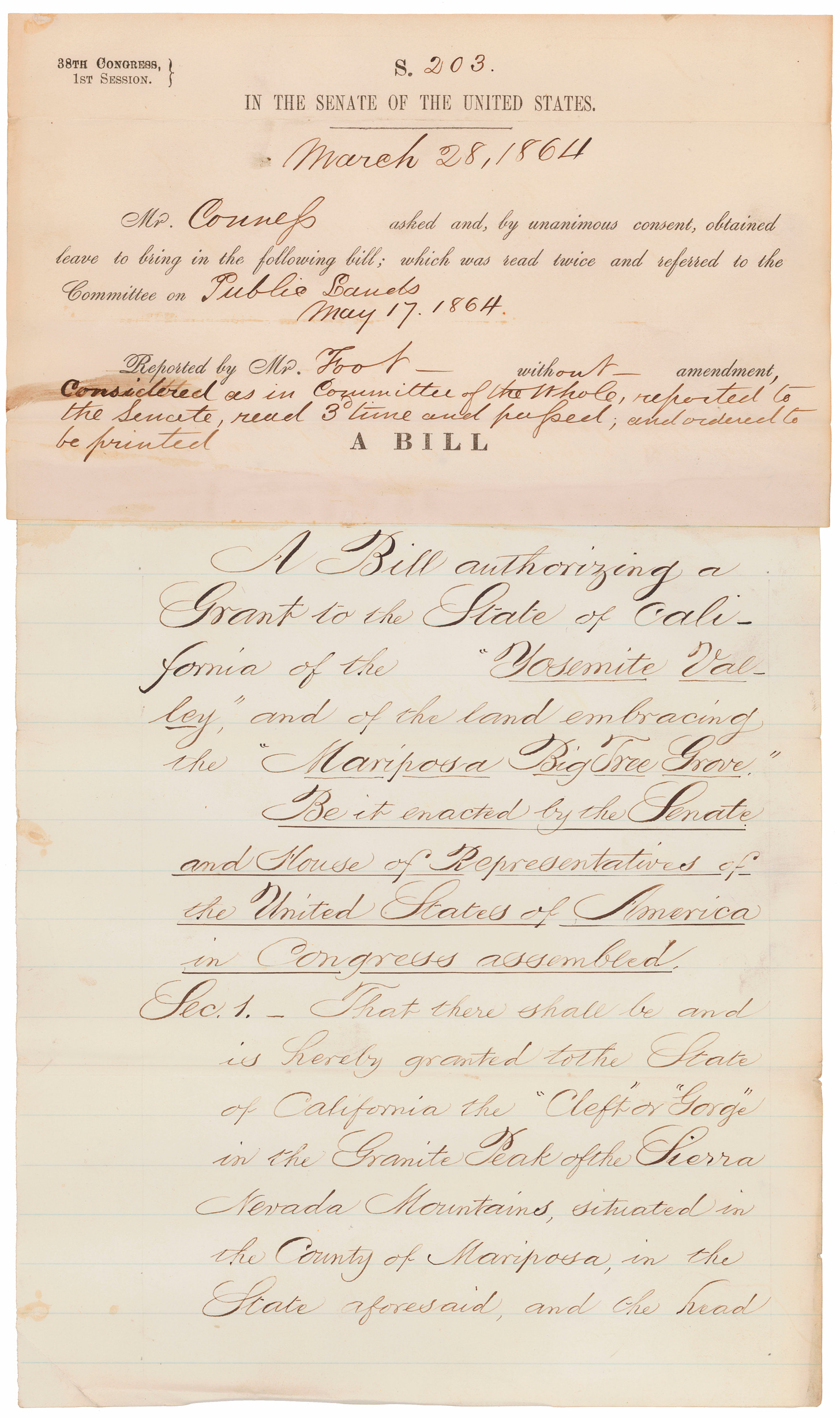

In 1864, Congress passed a short bill signed by President Lincoln amid the Civil War. The national government granted to California some federal land held in Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Big Tree Grove.

While most of the bill described the boundaries, Congress stipulated that California “shall accept this grant upon the express conditions that the premises shall be held for public use, resort, and recreation.” In addition to that, the state could never sell the land.

It took some time, but eventually this land and an expanded perimeter reverted back to federal control as a national park.

Yellowstone (1872)

Eight years later, Congress turned its attention to the strange landscape of Yellowstone with its odd geysers and thermal pools. In another short bill, Congress established another set of boundaries that would keep out settlers and industry. Congress directed that some two million acres be “dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.”

(Except for people who were already there; they “shall be considered trespassers and removed therefrom.” You get three guesses one guess who Congress meant.)

Besides establishing a “public park or pleasuring-ground,” Congress told the Secretary of the Interior to prevent “the wanton destruction of the fish and game found within said park, and . . . their capture or destruction for the purposes of merchandise or profit.”

The first American national park by name was thereby established.

Organic Act (1916)

Not wanting to rush things, Congress kept creating parks but neglected to create an agency to provide overall management. The Cavalry was in charge at Yellowstone for some time. Finally, in 1916, after various efforts, Congress created the National Park Service.

According to the enabling act, the purpose of the parks was “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

Sometimes people talk about the “dual mandate” in this statement. It is easy to see why, perhaps, from our standpoint after more than a century. To conserve nature unimpaired and to provide for the public’s enjoyment can often come into conflict. But not many people considered this in 1916.

Amalgams and Tradeoffs

The writer Wallace Stegner, cribbing from someone else, wrote that the national parks were “the best idea we ever had.” But it is not a single idea, as the phrases I’ve compiled above show. More usefully, Robert Keiter in To Conserve Unimpaired: The Evolution of the National Park Idea said national parks are “an amalgam of ideas that have evolved over time.”1

To think of parks as amalgams is helpful, I think. Most things are. They don’t come to us through time pure and uncomplicated. When we embrace an essentialist perspective, we lose some of the messiness of historical context, the layers of history and competing and complementary ideas.

I’ll confess: most of the time, I wish America’s “best idea” prioritized non-human landscapes and features along with plant and animal life. The human footprint is stamped heavily across the earth, so I lean heavily into “unimpaired” and the prevention of “wanton destruction.” But this misses the public, the “pleasuring-ground” part, the enjoyment that inheres in these places, by design. I recognize that importance, too, if occasionally belatedly.

Last week, I spoke to a longtime park employee, now retired almost two decades. He told me the job was (1) to protect the parks and (2) to serve the public. Service, he reminded me, was right in the name: National Park Service.

In my favorite history of the park service, Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History, the historian Richard West Sellars pointed out, “It is a significant, underlying fact of national park history that once Yellowstone and subsequent park legislation codified the commitment to public use and enjoyment, managers of the parks would inevitably become involved in design, construction, and long-range maintenance of park roads, trails, buildings, and other facilities.”2

All of this means capitalism has always stood as a partner in these places. And that complicates everything related to conservation. It is worth mentioning that the park at Yellowstone received a big boost from the Northern Pacific Railroad.

Probing the past reveals few simple lessons, but doesn’t make the effort wasted. Thinking of our current political leaders, we might recognize the language of legislation from generations past came from similar people. They had flaws, interests, myopia, incomplete information. The documents we like may be inspiring. They may be law (for now). They are products of people, rooted in time.

Relevant Reruns

In my very first iteration of The Library, I reported on a book about Yellowstone written in the 1930s. The first personal essay I ever published is about a quick trip in Great Basin National Park and how I should learn something from those who experienced the park in ways distinct from my preferences. (The essay starts on page 9 at the link.)

New Writing

I have a story out about the challenges of local meat producers.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

I return to The Field Trip next week. Stay tuned!

Robert B. Keiter, To Conserve Unimpaired: The Evolution of the National Park Idea (Washington: Island Press, 2013), xiii.

Richard West Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 10.