A priority of The Library part of my newsletter cycle is the structured opportunity to dive into (usually) older books. Sometimes I find a book I’ve long meant to read and other times I revisit one I’ve read before to test my memory against a fresh read. But the central task of reading an older book as a historian is to inhabit the intellectual space of another time. This is good practice in suspending judgments and promoting curiosity instead condemnation.

I didn’t know what to expect when I picked this week’s book, but I knew I wanted to get into the mind of conservationists from the mid-20th century. The book proved a good vehicle for that. Read on!

American Conservation In Picture and In Story

American Conservation in Picture and in Story originally appeared in 1935 in the pages of American Forests, the magazine published by the American Forestry Association. At the time, Ovid Butler edited the magazine. So popular was the issue, the organization republished it as a book later in the year. Then, a couple more printings happened. The edition I own appeared in 1941 and became the first text that merited a revision. (The one linked above is from yet another edition a few years later.) Butler wrote most of the chapters; the other authors are somewhat obscured in only a brief editorial note and not highlighted in the table of contents.

The book’s pages are regular-sized notebook paper size, which makes it large. The text comprises about 30 chapters, each two to eight pages with illustrations on each page. The chapters furnish short overviews of key conservation topics, often with updated statistics. Taken together, the book covers a sprawling landscape with relevant information, even if the format (“in picture and in story”) could not hope to be comprehensive. A reader would leave the book well-informed – within the values framework offered by it.

The American Forestry Association formed in 1875 and pitched itself as the first organization to push conservation into public consciousness. The AFA supported many of the early federal conservation measures, advocating through its journal first known as Forestry and Irrigation (a source for early research I did as a graduate student) and American Forests at the time this book appeared.1 Over time, the organization’s position in political fights swung to various points on the political spectrum.2 The pages of American Conservation demonstrate positive reactions to conservation, whether it came from state or federal governments. (Industry perspectives remained a muted force in the book.)

Why Read This Book?

This is the key question for any book, right? You might read a book for sheer enjoyment. This book isn’t the right genre for that. You might read a book for information. This book includes plenty of information, but if you want either depth of information or the most updated data (for today), it fails to deliver. That’s not its purpose. So why read it? In 2023 no less.

Often when you specialize in research, you get deep in the weeds on a topic, overly familiar and too comfortable with scholarly takes. When that happens, it is useful to get back to original sources. Although I figured I understand what midcentury conservationists thought, I decided it was worth my time to ground truth those ideas. If American Conservation In Picture and In Story wasn’t going to tell me the most sophisticated scientific information, or the greatest details on conservation policy, what it could do is reveal some of the general values the AFA sought to present as the Depression started winding down.

When doing this sort of reading – the most critical task for a student of history, no matter their experience – you have to remember that the book (or letter or photograph or whatever the source) was produced in its present, not our past. Remembering this and working to see the time and culture that produced the source takes a lot of work. It is what one expert aptly described as “an unnatural act.”

The Frontier Remains

Many of the first chapters in American Conservation recap history. (It gets a little repetitive in fact.) To say the interpretation lacks subtlety is an understatement. The authors dismiss the continent’s original citizens in a few words (even if later in the book there is some acknowledgement of the obvious injustices). The writers also speak frequently of “man’s conquest of the earth” and similar expressions like, forests “waiting there for man’s harvesting.” These perspectives dominated earlier times, and seeing them in print is a good reminder that language of conquest that now sounds a sour note easily tripped off the tongues of earlier generations.

It is the language of the frontier.

A (Relevant) Digression

At the end of the 19th century, a palpable sense settled over American artists and writers and much of the general populace that an epoch was closing. A young historian named Frederick Jackson Turner put it in its most formal form in an address before the American Historical Association in 1893. “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” portrayed the frontier (what Turned characterized as “the meeting point between savagery and civilization”) as what distinguished American history from other places. The westering impulse defined America.

Turner stated his thesis simply, “The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development.” Turner went on to describe that advancement and how settlers became American on that frontier where they reinvented themselves and built communities democratically. This mattered to Turner and his contemporaries because in 1890 the Superintendent of the US Census announced that the frontier had disappeared. If the defining feature of American history disappeared, what would now define Americans?

Scholars have quibbled and outright rejected much of this interpretation. Pretty much all of it, in fact.

Yet the idea (and the anxieties) persisted. When Franklin Roosevelt sought the presidency the first time in 1932, he addressed San Francisco’s Commonwealth Club and offered a similar rendering of the American past. As long as “free land” existed, he said, “equal opportunity for all” existed, and government appropriately stayed out of business’ business. That no longer accurately described the situation, though. The land was gone; the economy was overbuilt; people were living “drab” lives. “Clearly, all this calls for a reappraisal of values,” Roosevelt argued.

Our task now is not discovery, or exploitation of natural resources, or necessarily producing more goods. It is the soberer, less dramatic business of administering resources and plants already in hand, of seeking to reestablish foreign markets for our surplus production, of meeting the problem of underconsumption, of adjusting production to consumption, of distributing wealth and products more equitably, of adapting existing economic organizations to the service of the people.

All of that focused mainly on economic priorities. But it applied just as well to the history of resources and conservation.

Conservation As Postfrontier

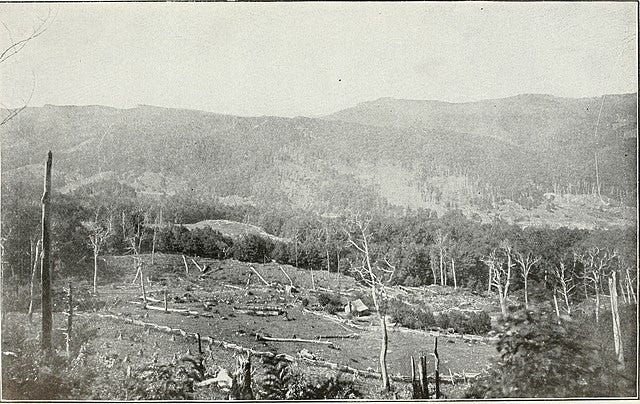

From the perspective of American Conservation, the conservation movement was a postfrontier movement. In the chapter on the history of lumbering, for example, the author pointed out that there was “no profit in forest protection” for millowners. When the frontier remained available, resources seemed inexhaustible and no reason to act conservatively appeared relevant.

Over the course of the 19th century, an awakening gathered momentum. By the 20th century, conservationists prevailed – at least sometimes – to slow the wastefulness inherent in the inexhaustible frontier mindset.

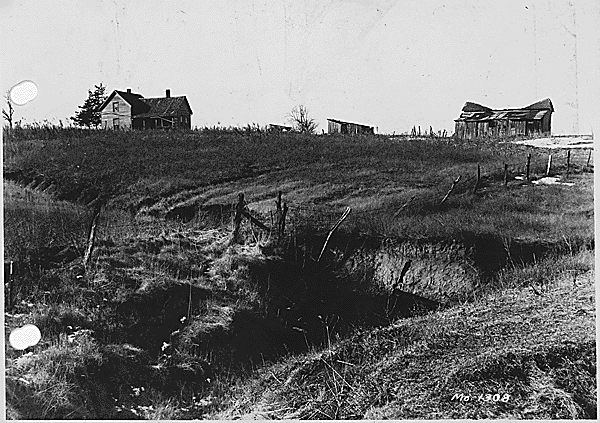

The majority of the book’s chapters conveyed the steady, if incomplete, progress toward stewardship instead of conquest. The chapter “Conservation of the Soil” presents this most obviously perhaps:

The old era of farming for production’s sake is being transformed into a new era of husbandry. Slowly but surely the day of soil exploitation is passing and in its stead is arising a genuine interest in soil conservation.

That’s about as efficient a summary of the book as is possible.

In chapter after chapter, topic by topic, American Conservation condemns longstanding practices and praises emerging changes in parks and forest management, in research into pests and fire and wildlife, and in new government programs designed to promote what we would call sustainability. Given the publication and revised edition date, it presents a clear window into Depression-era worldviews.

Closing Words

Virtually all my scholarly publications focused on conservation in some form. But because so much of American Conservation focused on forests in the early 20th century, I was reminded many times of an article I co-authored with a student about efforts to stop blister rust in Northwest forests around the same time. (It’s more interesting than it sounds, I promise!) You can read it here. Another short column I wrote about New Deal-era forestry reforms might also be worth reading, I think, because you can see how long the charge of socialism has plagued conservation. This is not a charge made in American Conservation but did circulate around this time.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

Next week is The Wild Card. You’ll have to check back in to see what I have in store for that. Stay tuned!

If you enjoyed this newsletter, press the Like button below or leave a Comment. If you know others who might enjoy this weekly newsletter, share it with them. And if you are able, consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Thank you for reading.

In my first published scholarly article, I cite articles from Forestry and Irrigation.

On the AFA, see Stephen R. Fox, The American Conservation Movement: John Muir and His Legacy (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985); Samuel P. Hays, Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: The Progressive Conservation Movement, 1890-1920, new edition (New York: Atheneum, 1975); James G. Lewis, The Forest Service and the Greatest Good: A Centennial History (Durham, N.C: Forest History Society, 2005); Harold K. Steen, The U.S. Forest Service: A History, Centennial Edition (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2004).