A historical moment I included in my 2020 book An Open Pit Visible from the Moon keeps floating into my mind. For The Library this week, I wanted to share it, contextualize it, and reflect on it. Read on!

The Moment

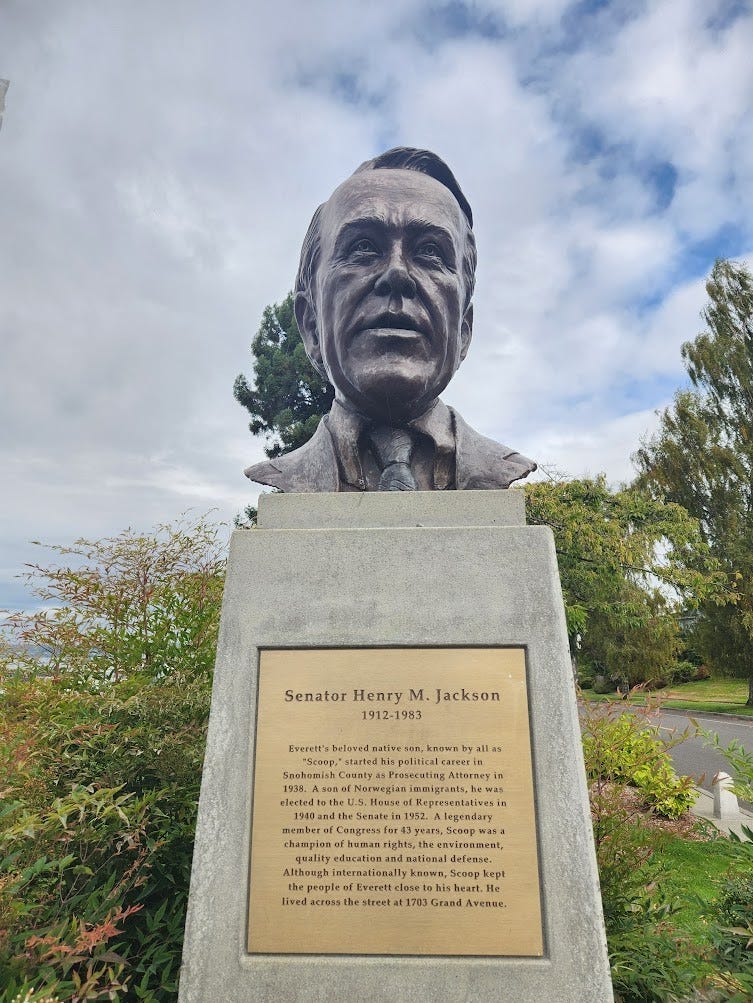

In the early 1960s, conservation activists from Washington state visited the nation’s capital and met with powerful leaders. One of them was the state’s junior senator, Henry “Scoop” Jackson, who was a significant force for environmental legislation. The activists sought Senator Jackson’s support in their campaign to establish North Cascades National Park.

According to the account of Harvey Manning in the semi-official, always-irreverent Wilderness Alps: Conservation and Conflict in Washington’s North Cascades, Jackson listened to them and then explained how the political system worked.

“I can’t give you a national park,” the senator lectured. “But if you get up a big enough parade, I’ll step out front and lead it on in.”

It is the sort of remark those who knew or have studied Jackson recognize as characteristic of his way. In other words, the story rings true.

Few Washington politicians ever did as much for the state as Jackson, so I need to trust his analysis of how the political system worked then. He knew how to accomplish things.

I shared the story in my book in a chapter on the creation of that park (and how it connected to a potential mine that might have been, but wasn’t, included within the park boundaries). I shared it because it was illustrative and a bit humorous in its folksy wisdom — academic books have too little humor.

Now, I’ve come to question this sentiment, at least partly.

The Context

I’ll explain my rethinking but first some context.

The history of conservation in the North Cascades is long, and I won’t include all the details.1 The Forest Service administered most of the North Cascades at the start of the 20th century. Many millions of acres were managed as wilderness, mostly de facto but some large stretches in administrative categories (e.g., primitive area). And when the Wilderness Act passed in 1964, Glacier Peak Wilderness became one of the original legislatively protected areas.

In most respects, the Forest Service led in wilderness protection going back to the 1920s. The National Park Service, by contrast, earned a reputation for developing its lands for tourism in ways the put off wilderness activists. But by the mid-20th century, Northwest conservationists had nursed a well-earned suspicion about the Forest Service, which seemed bent on supporting the timber industry at virtually every turn.

So by the 1960s in the North Cascades, they advocated for a national park — something the Forest Service fought to maintain their administrative control and priorities. By the mid-1960s, it became one of the most significant conservation fights in the region. A series of public hearings demonstrated widespread grassroots support for the park, as well as diverse ideas for how the boundaries should be drawn and what kind of park it should be.2

In 1968, Congress finally came to terms and wrested away a big chunk of land from the Forest Service and put the National Park Service in charge. For local activists who long fought the Forest Service, taking away land under its control brought delight.

The Rethinking

Back to Jackson.

The senator’s lesson about needing a parade to get in front of seems like a necessary one. And a parade built strong in the Northwest.

When the House Interior Committee met in Seattle in April 1968, its chair, Wayne Aspinall, a prickly conservative Democrat from western Colorado who had a fraught relationship with Jackson, was greatly annoyed by local activists. The hearing was booked in a room with 130-person capacity; more than 800 showed up. “I don’t know who these people are,” Aspinall complained. “Are they hippies or part of a Seattle drive to get out into the country?”

What the often-obstructionist Representative missed was that they were citizens.

The public represented a wide collection of interests and welcomed a national park. Jackson had his parade, and true to his word, he marched it to the finish.

As I understand (and told) the story, this is about the success and persistence of grassroots activism. Part of that story is linking with politicians who can help channel local activism into national legislation.

However, in recent years, I’ve craved political leadership at times. I’ve wanted political leaders to not step in front of a surging wave of the public and ride them in to power or legislative victories. I’ve wanted them to take an unpopular, but morally correct, stand and explain why their constituencies are wrong or why the consequences of the popular idea would harm others.

I have observed political leader after political leader, especially in the Republican Party, acquiesce to things they know are wrong because their constituents demand politicians believe things that are not true. (We know they do this, because we can find all sorts of prior statements announcing their principles that they have forgotten, misplaced, ignored.)

Rather than stepping in front of a mob moving east, I want political leaders to stand in front, facing west, and say, “Stop. Here are reasons to pause, to reconsider. This is what I have learned. This is what I know to be true. It would feel good to go along with you, but I cannot acquiesce in good conscience.”3

We know from public opinion polls that US citizens find Congress deplorable. We also know they like their representatives. What if those representatives found fidelity to truth rather than popularity and power? What if they were leaders, rather than followers? Sometimes elected representatives need to stand their ground.

Closing Words

Relevant Reruns

You can read my account of Harvey Manning and his book that was written for the North Cascades campaign here, and my very first newsletter covered some of this history, here. I wrote an account of one of the protests aimed to stop the Kennecott mine here.

New Writing

Last week, I reported a story about the 50th anniversary of a Northwest organization dedicated to organic farming and gardening, Tilth. I enjoyed the conversations I had as part of the reporting. Find it here.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

I’m heading out on the road so should have a fresh place for The Field Trip next week. Stay tuned!

Two friends have written accounts that would provide extended coverage. See the relevant sections of Kevin Marsh, Drawing Lines in the Forest: Creating Wilderness Areas in the Pacific Northwest (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2007); and Lauren Danner, Crown Jewel Wilderness: Creating North Cascades National Park (Pullman: WSU Press, 2017).

My interest in the creation of the park is almost as an aside. As part of the public park campaign, many advocated to include Glacier Peak Wilderness, in which Kennecott Copper Corporation planned an open-pit mine. Including this area, activists believed, would stop the mine. My book focuses on this campaign that intersected with the larger North Cascades National Park story.

I am not suggesting that in this particular case that Jackson should have stopped the parade. The campaign in this case was not about to cause great harm.

Senator Tester made a comment similar to Jackson's to conservationists about the Blackfoot-Clearwater Stewardship Act a few years back. "That's a great idea, now make me do it".

As far as the rest of the essay, I suggest an important difference between grassroots activism for an action and leading on morality issues.

EXCELLENT!