A Monumental Sadness and a Paradoxical Legal Tradition

Indigenous peoples and the Antiquities Act

A Note as 2024 Comes to a Close: Thank you for reading Taking Bearings. I’ve sent out almost 150 of these essays. It astounds me that people keep signing up and reading them. What a gift it is to be able to share these perspectives with you! I am grateful for your support. In 2025, I’ll be making some adjustments to Taking Bearings. Subscribers will not have to do anything, but sometime in January, things will begin to look slightly different. I hope you’ll stick around to see what else is coming.

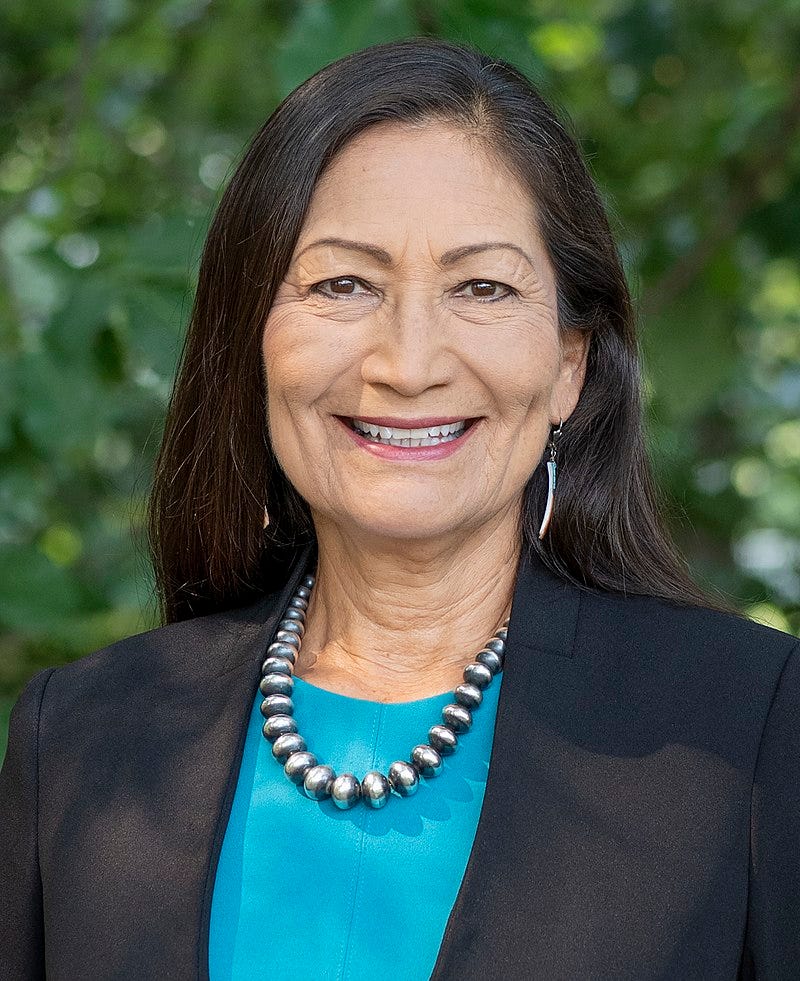

Last week, President Joe Biden created a new national monument, the Carlisle Federal Indian Boarding School National Monument. It caps work done by Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland through her tenure to address Indigenous issues seriously and centrally. Losing her as interior secretary is going to be an enormous change—and not a good one.

For The Classroom this week, I want to spend a bit of time on those boarding schools and the power the president used to create the national monument. Read on!

Boarding Schools History

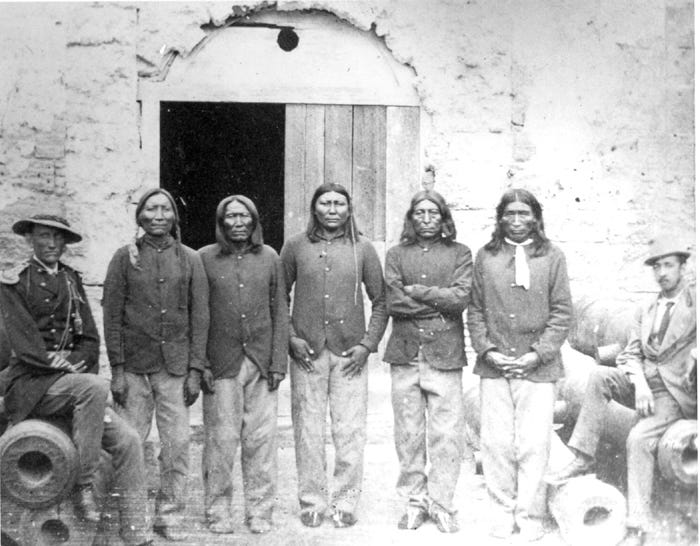

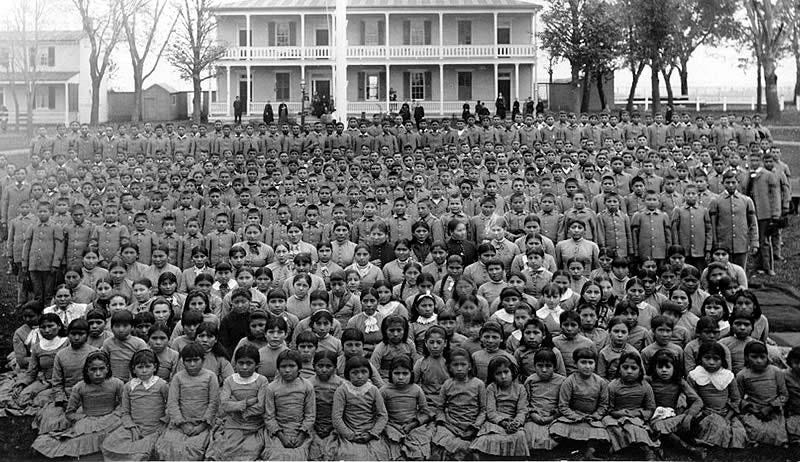

The historical record offers little good to say about Indian Boarding Schools. No matter how much their champions believed they would offer a pathway to knowledge and active citizenship, they were conceived with the idea that Indigenous cultures were not only inferior but needed to be eradicated. The famous line you’ve probably read from Richard Henry Pratt was that the schools should, “Kill the Indian in him and save the man.”

Children at these schools suffered abuse in all the ways imaginable—and some unimaginable ways. Separated from families, children lived in often unhealthy and cramped schools. Their names were taken. Their language was suppressed. Their hair was cut. They were forced to work. They had to eat unfamiliar and often unhealthy and unappetizing foods. And many died, almost 1,000.

(I’m going light on details here, because it’s some of the most difficult material to confront in American history. But you may investigate on your own.)

Conditions were known at the time when these schools operated most widely. A scathing report in 1928 enumerated many of these and related problems. Despite this, thousands of children survived. Mitch Walking Elk captured this, “They put me in the boarding school and they cut off all my hair, gave me an education, but the Apache’s still in there.”1

Examining this History

The boarding schools affected many Indigenous families, including Secretary Haaland’s. In a Washington Post editorial, she explained,

I am a product of these horrific assimilation policies. My maternal grandparents were stolen from their families when they were only 8 years old and were forced to live away from their parents, culture and communities until they were 13. Many children like them never made it back home.

She described hearing stories from her grandmother:

She spoke of the loneliness she endured. We wept together. It was an exercise in healing for her and a profound lesson for me about the resilience of our people, and even more about how important it is to reclaim what those schools tried to take from our people.

Building on this personal and historical understanding, Haaland led a Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative to investigate the nature and consequences of the system. The effort revealed more boarding schools than had been known before.

After the first volume of the report was released Haaland announced the next phase, A Road to Healing, which includes investments in reviving Native languages and returning the remains of children who died at these schools.

Out of this initiative, President Biden also issued a formal apology in October, calling it one of the “most horrific chapters in American history.”

The Paradoxical, Evolving Antiquities Act

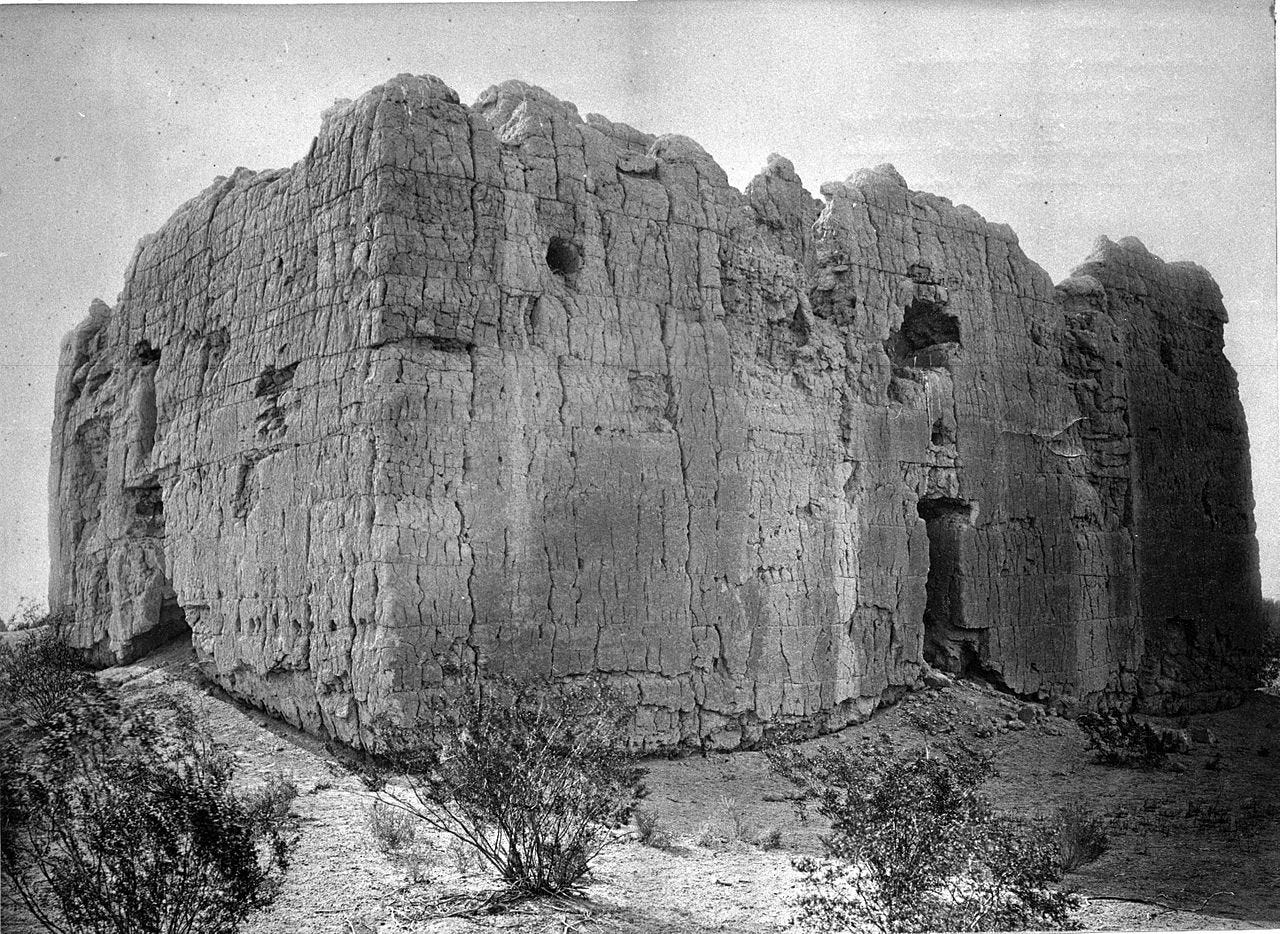

Now, in December, Biden used the Antiquities Act to create the new national monument—and other national monuments with Indigenous support may be possible. In some quarters, the Antiquities Act has become controversial over the last 30 years.

Congress passed it in 1906 mainly to protect Indigenous artifacts from pothunters and others who were desecrating sacred sites. The Antiquities Act allowed presidents to protect “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interested” on federal lands.

Because it allows executive action, the Antiquities Act became a way for presidents to act quickly when Congress wouldn’t. In the case of ransacking historic sites, time often was of the essence. In addition, several times presidents have used it to protect a landscape as a national monument that later became, through Congressional action, a national park, such as Grand Teton and Grand Canyon.

The Antiquities Act’s history with tribes is complicated and has evolved.

(I would need to learn a lot more to write definitively about this, so consider these thoughts a tentative grappling only.)

The law was designed to protect Indigenous artifacts from being taken by private collectors and damaged by the public. However, for much of its history, it operated to keep away the descendants of those sacred sites. In this way, the Antiquities Act alienated Native peoples from land and cultural artifacts remains that were theirs. This is part of the same history as the boarding schools where Tribes were not allowed to exercise their sovereignty.

Yet, in recent years, tribal groups have come together to ask for a partnership with the federal government to protect lands with this law. The most famous example of this is Bears Ears National Monument, created by Obama, hollowed out by Trump, restored by Biden, and on the chopping block again. The Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition has been in the forefront in building support for Bears Ears and in its co-management, a growing trend in conservation that benefits tribal sovereignty and ecosystems.

Now, with the Carlisle monument (and potentially other sites), the Antiquities Act is again being used to highlight Native history and experience—although this time with more input from Tribal leaders.

The Uncertain Future

Rumblings are growing louder to strike the Antiquities Act from the record, removing this critical power from future presidents’ power to use for conservation. Not only would this harm conservation efforts, though; it likely would weaken tribal sovereignty. These are not disconnected, of course.

Closing Words

Relevant Reruns

I have written about the Antiquities Act before in this newsletter and elsewhere. The previous Trump administration’s actions toward Bears Ears riled me up enough to write an op-ed.

New Writing

Only gestating work at the moment. But be sure to read my interview with Steve Edwards, if you are a paid subscriber.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

This year, the Christmas and New Year holidays fall on Wednesdays, my newsletter publication day. You can likely expect briefer newsletters over the next two weeks, as well as my apology for filling your inboxes on holidays. The Field Trip is on tap for next week. Stay tuned!

Quoted in Brenda J. Child, Boarding School Seasons: American Indian Families, 1900-1940 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998), 8.