At a local gathering of farmers and agricultural experts last winter (or the one before that), a prominent — and outspoken — local farmer said, “No one has done more for the environment than farmers,” or words to that effect.

This grand claim would surprise some environmentalists who might be more likely to say, “No one has done more to harm the environment than farmers.” Or the deliberately provocative (and frequently wrong) Jared Diamond who once claimed agriculture was, “The Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race.” I am not going to adjudicate any of these claims (other than to say that I do not respect Diamond’s work), but they demonstrate a debate over the relationship between farming and conservation is long-standing.

In 1939, the conservationist, professor, and writer Aldo Leopold published “The Farmer as a Conservationist” in American Forests (after first appearing as an extension circular for the University of Wisconsin’s College of Agriculture).1 For The Library this week, I’m digging into that piece. Read on!

Aldo Leopold’s Many Legacies

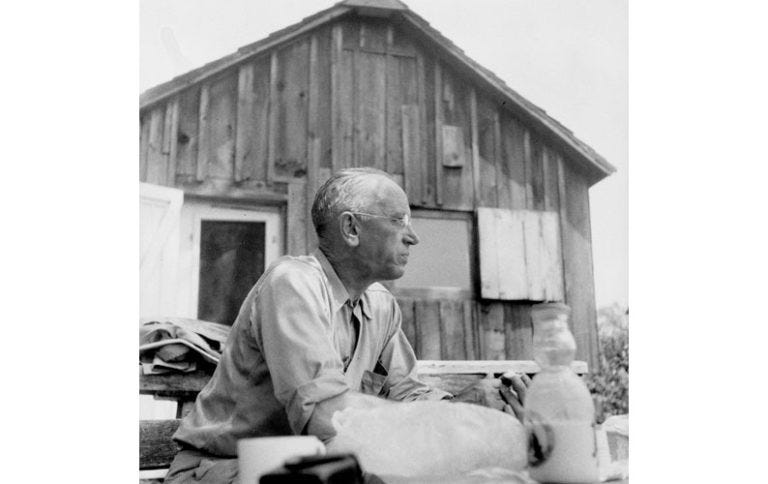

Leopold has appeared a few times in Taking Bearings, but I have never focused an entire essay on him.2 So, it is past due.

Few conservationists have played as powerful a role in environmental history as Leopold. He worked for the US Forest Service and as a university professor, along with a few other jobs along the way. For most of his life, Leopold lived in the Midwest, although an early stint in the Southwest powerfully shaped conservation there and his worldview.

Trained as a forester, Leopold also possessed a poet’s heart. His ability to convey important ideas beautifully is not least among the reasons we remember him. His A Sand County Almanac is arguably the most important book in the American environmental canon. In it, he conveyed his land ethic, which was and is an essential extension of ethics that guides many individuals and institutions. Leopold also was one of the founders of the Wilderness Society, and his ideas about wilderness continue to influence politics in that realm.

Because of all this, people can forget his ideas about farming and conservation on private lands. That’s a short-sighted omission, especially because, as he put it, government alone cannot do the work. “It is the individual farmer who must weave the greater part of the rug on which America stands,” he wrote in “The Farmer as a Conservationist.”

“The Farmer as a Conservationist” Ideal

This essay, first delivered as a public talk, opens with a simple line:

Conservation means harmony between men and land.

Through the rest of the essay, Leopold showed the ways farmers had disordered that harmony and explained how he thought farmers could and needed to adjust to become conservationists.

The North American continent had become impoverished through European settlement. Too many losses in soil fertility, decline of flora and fauna, and depleted waterflow had changed the face of the land. Some change, Leopold acknowledged, was necessary, but far more happened through indifference. He also aimed to dispel the idea that the land was exhausted and thus could just be restored through restrained use. Instead, Leopold claimed that many resources were knocked out of order or disappeared entirely. Restraint could not resolve that.

In the essay, Leopold struggled to balance a positive vision of what he saw as “right” with the evidence that told him that “wrong” was more common. So while he could bemoan too much timber cutting or too many deer (without natural predators) or draining ponds unnecessarily, he also praised his ideal: land in working order.

Getting land in working order required know-how.

Conservation . . . is a positive exercise of skill and insight, not merely a negative exercise of abstinence or caution.

His perspective here is important. Leopold was not holding conservation up as a program of laws to prevent people from doing one thing or another. In fact, he also wrote, “I have no hope for conservation born of fear.”

Instead, conservation was ideally an intelligent program. To work, he said, it must “evoke” farmers’ skills. Subsidies or education — common parts of conservation in the 1930s and after — might get farmers to surrender. But if conservation drew on their skill, farmers would come to it with “enthusiasm and affection.” This was the ideal Leopold pursued in “The Farmer as a Conservationist.”

Surmounting Obstacles

Sometimes ideas become dictators, Leopold asserted. “Ruthless utilitarianism” was such an idea. This perspective led to what Leopold characterized as, “Everybody worried about getting his share; nobody worried about doing his bit.” (This may be one of his best underappreciated aphorisms.)

Properly pursued in the Leopoldian way, conservation would mean farms would leave some land in woods, some in ponds and marshes, some with windbreaks, and all of these areas would help birds, mammals, amphibians, plants, even just scenery. Would farmers do this with ruthless utilitarianism guiding them? Returns on profit were powerful motivation. What about things that profit the community?

Leopold thought windbreaks offered an example of community good — once enough individuals planted them. Such additions to the landscape provided good habitat for all sorts of flora and fauna. Knowing how the pieces fit tested farmers’ skills. After all, he said:

The landscape of any farm is the owner’s portrait of himself. Conservation implies self-expression in that landscape, rather than blind compliance with economic dogma.

The more farmers understood, the deeper the conservation that could be practiced. The landscape could then move toward wholeness, and that wholeness would mix wild and tame pieces “all built on a foundation of good health.”

This conservation vision, it seems to me, still has not found a wide enough audience.

Postscript

I have to admit when I first heard that local outspoken farmer’s comment, I did not recognize any echo of Leopold. And I have not been on his farm to ground truth his claims. But if I were invited, Leopold has given me things to look for and questions to ask.

Closing Words

Relevant Reruns

This old newsletter sets some of the context for this week’s contribution. Leopold played a role in the lead for this article about the Endangered Species Act

New Writing

I contributed a guest post to

’s Substack called “Changing Seasons.” It’s a brief essay that gets a little into my evolution toward more creative writing. You can link below:My last book, Making America’s Public Lands: The Contested History of Conservation on Federal Lands, is out in paperback tomorrow, which means it is now available at a slightly lower cost! I hope you’ll consider purchasing.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

Tomorrow, if you are a paid subscriber, you will have access to this month’s interview. It’s an excellent one you won’t want to miss! Upgrade to gain access to it and all the interviews (and to support my work).

Next week, it will be time for The Wild Card. Stay tuned!

The article I have linked is a typescript distributed among Soil Conservation Service workers with a Foreword that read: “Those of us engaged in broad action programs sometimes tend to lose sight of individual values in conservation. Here, Mr. Leopold reminds us of these and what they mean for the community and for the future of better land use.”

Except for when I was an undergraduate and he was the subject of my American Environmental History class’s term paper.

You don't need to be invited to Leopold's shack near Baraboo. It is open to the public and you can talk with folks there at the Leopold Foundation. Leopold's primary conservation work with farmers was in western Wisconsin at a place called Coon Valley.