Reporting Back

First off, a quick report on feedback from last week’s one-year anniversary newsletter.

I included two polls. In one, I asked about the length of these newsletters. No one said they were too short, and only a couple thought they were too long. So I’ll likely be making only minor adjustments, shaving words and paragraphs when I can.

The other poll offered more interesting information. As I explain on my About page, I cycle through four types of post: The Classroom, The Field Trip, The Library, and The Wild Card. I was curious about your favorites – or whether you paid any attention to this scheme. To almost one-quarter of you, this cycle was news! To half of you, The Field Trip is a favorite. (Mine, too, generally.) The remaining handful split between to other options. I’m taking it as a good sign that every option was someone’s favorite. I’ll keep working enliven each type.

To those of you who offered other feedback in the Comments section or via email, thank you.

Last, I want to remind you that through August, I’m offering a discounted paid subscription. Use the links below to upgrade or give a subscription.

Zoning: Conflicts and History

In my county, I’m tracking a local conflict that centers on zoning, one of the most powerful land-use planning measures available. Simple, even mundane, zoning regulations shape all of our communities deeply. I figured it was time to brush up on the history. Read on!

The Problem

Cities have zoned areas for certain activities – and against others – for more than a century. Courts have upheld this power generally. On occasion, questions and controversies arose about whether governments could restrict what individuals and corporations could do with their property, a classic debate about individual rights and the public interest.1

Although this long history exists, the critical moment that accelerated zoning came after World War II. Suburban sprawl ate up more and more countryside. For instance, Oregon’s population grew 50% in the 1940s, a rate second only to California. To house this booming population, homes (and businesses that supported those who lived in them) grew where crops once did. In the Willamette Valley, 500,000 acres of farmland disappeared between the mid-1950s and mid-1960s – a loss of 20%.2

The story repeated itself across the country, and opponents looked for ways to control this pell-mell development. States took the lead, because local governments wouldn’t. Hawaii created the first state planning law in 1961. Others followed suit in the 1960s and after.

Going National

While states innovated with various land-use planning schemes, national efforts grew.

On New Year’s Day 1970, President Richard Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Act, which required planning and assessments for any development project on federal lands or by a federal agency. Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson, a Democrat from Washington, came out in favor of what he thought would be the next logical step: a National Land Use Policy Act.

The Nixon administration had its own alternative. The existence of a campaign – in both parties – to develop a national land-use planning initiative demonstrates a consensus around the problem of sprawl and unplanned land development.

For five years, compromises inched forward, but by the mid-1970s, amid rising ideological opposition, the federal approach died.

But meanwhile, states kept working.3

Oregon

Oregon was an exemplar.

The state had enabled zoning with laws passed in 1919, 1923, and again in 1947. None was effective. At the same time, Oregonians developed an identity where living a good life in a good land was central. Along with growing pollution, unplanned growth was jeopardizing that identity and pushed coalitions toward reform.

In 1961, for example, the state adopted an “exclusive farm use” zone to limit property taxes on farmland to reduce one pressure farmers faced that encouraged them to sell to developers. It didn’t work. A few years later, legislators tried another method . . . that didn’t work. Statewide land-use planning seemed the only way.

Into the fray stepped Republican Tom McCall who Oregonians elected governor in 1966. Livability was the centerpiece of his policy agenda, as he promoted Oregon’s special relationship to the environment and worried about overdevelopment and crowding. He received national notoriety in 1971 for saying,

Come visit us again and again. This is a state of excitement. But for heaven’s sake, don’t come here to live.

In 1969, Senate Bill 10 passed. It required every county to develop a zoning plan, or the governor’s office would. Ultimately, according to historian (and friend and Taking Bearings reader) Derek Larson, the law ended up no more than a “token gesture.” But the issue persisted.

Dairy-farmer-turned-state-senator Hector Macpherson developed a new, more stringent law, Senate Bill 100, hoping for some relief. During the legislature’s opening session, Governor McCall addressed the politicians with urgency, saying,

The interests of Oregon for today and in the future must be protected from the grasping wastrels of the land. We must respect another truism – that unlimited and unregulated growth, leads inexorably to a lowered quality of life.

With rhetoric like that, McCall received credit for SB100 across the nation for a new land-use planning regime.

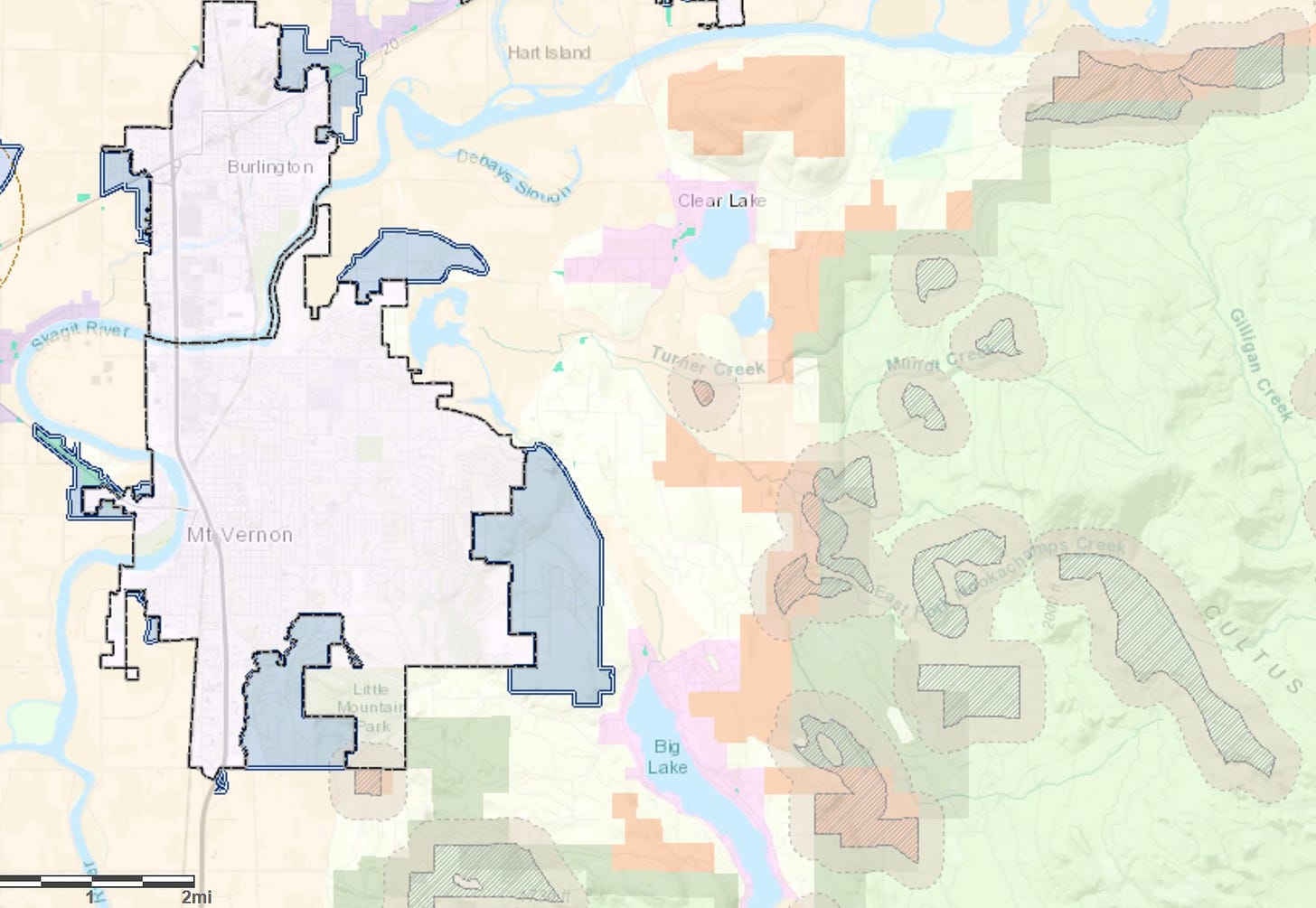

The plan allowed for local planning but consistent with overarching state goals. It also created a Land Conservation and Development Commission to review local plans. This layered approach ensured passage, if not universal popularity. Three times in the years after SB100 passed voters upheld it after citizen campaigns to repeal it put it before voters.

Assessment

Whether it worked might be the subject of another day. For now, what may be worth remembering is the sources of concern: unregulated development in rural areas (as well as along the Oregon coast) that reduced open space and crunched rural landowners.

These spaces, where the urban and rural rub against each other roughly, reveal our neighbors and our politics sharply.

Final Words

I may have more to share about zoning questions soon. In the meantime, an account of the National Environmental Policy Act is here. Also, I once wrote a bit of a think piece about getting to the public interest, a topic that feels relevant here.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

I go on The Field Trip next week, and I have a fascinating one to report on, a bit off my normally well-trodden path. Stay tuned!

A persistent interest of mine is how the public interest applies to land in a nation dedicated to private property. “Public Interest” is in the title of my 2020 book, and public lands, the topic of my 2022 book, are interesting to me in large part because so-call free enterprise sits uneasily there.

The Oregon material, here and below, comes from Derek R. Larson, Keeping Oregon Green: Livability, Stewardship, and the Challenges of Growth, 1960-1980 (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2016), chs. 6-7 passim; and William G. Robbins, Landscapes of Conflict: The Oregon Story, 1940-2000 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2004), ch. 9.

I relied on Adam Rome, The Bulldozer in the Countryside: Suburban Sprawl and the Rise of American Environmentalism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001) for the national perspective.