Why Are Dams Licensed (and Re-licensed)?

Investigating the origins of the Federal Water Power Act (1920)

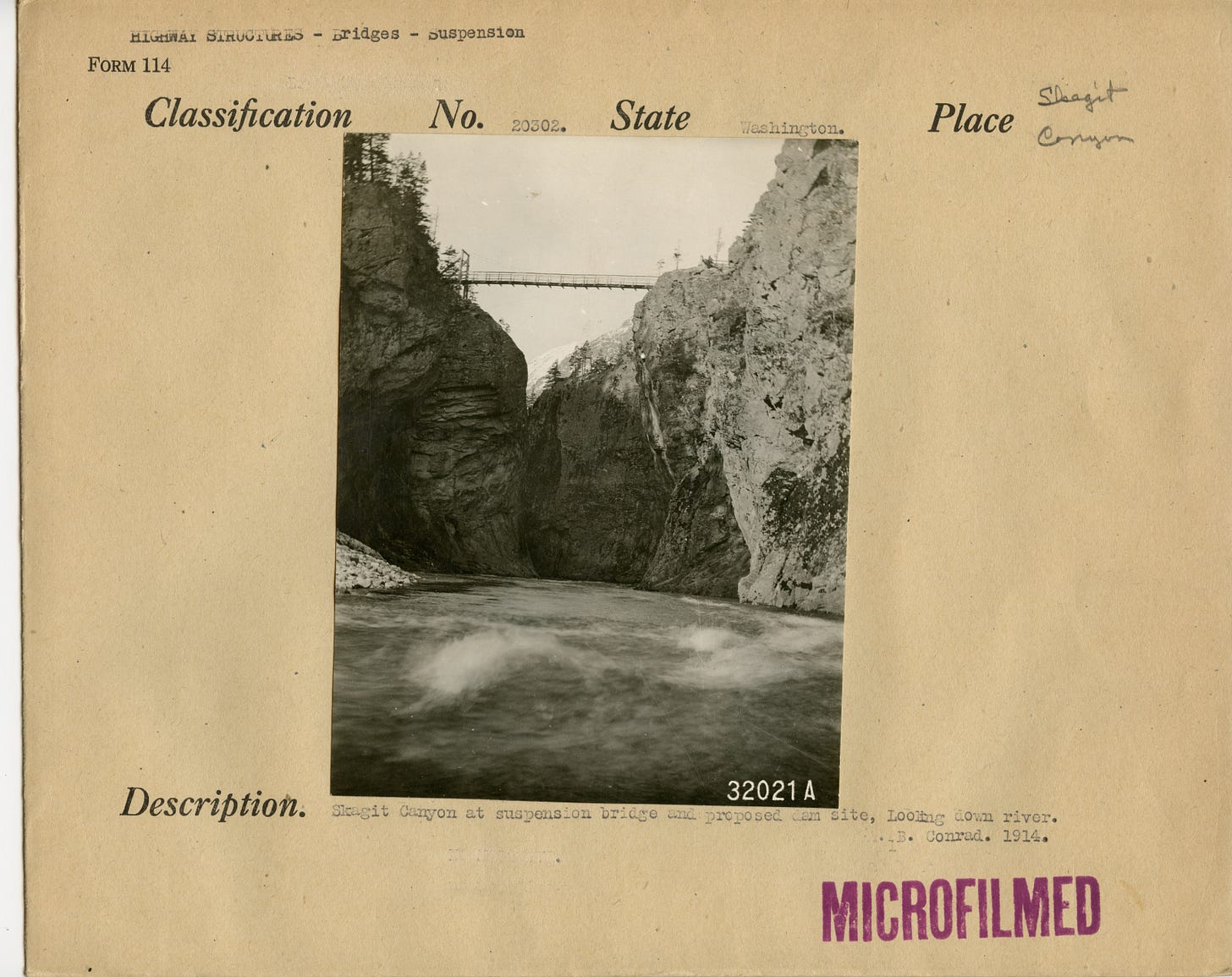

One of the more significant public processes underway where I live is Seattle City Light’s relicensing of its three dams on the Skagit River. Dams do not come up for relicensing often, so the process provides a rare opportunity for the public to press for changes. In the case of the Skagit River dams, fish passage for anadromous fish – or even dam removal – and how Tribal rights are recognized are driving interest.

I’ve been paying attention to this issue as a citizen and also for an ongoing project I’m writing about the river. I realized I held a fuzzy sense of where the licensing process originated. So for this issue of The Classroom I decided to investigate the origins. Read on!

Tapping White Coal

“Every mountain brook, bursting over the edge of a precipice and plunging into the bed of a ravine below; every leaping rapid, smothered in its own foam; every swift-running river, across which a dam can be placed to improve navigation, is a mine of the new fuel, white coal, eternal and inexhaustible. The mining of this new fuel has become one of the greatest industries of the day; but we are only seeing it in its infancy. For generations it will go on developing and increasing, becoming at every step more wonderful and more perfect.”

These words of a journalist resemble the energy of the unruly streams he hoped would funnel through hydroelectric dams, becoming eternally perfect. This enthusiasm reminds us of the transformative potential hydropower offered a century ago, a time when the complications of dams attracted little attention.

As electricity expanded, utility companies searched for sources of power they might tap. Public lands not only held many deposits of coal and other fossil fuels but also most of the good sites for hydroelectric power. Yet land agencies and the federal government had no clear strategy for the dams that were coming.

Lack of Policy

During his administration, Theodore Roosevelt pushed Congress to develop policies that would stop the taking of public resources without payment. Roosevelt especially wanted some sort of compensation energy sources – minerals or dam sites. He imagined some sort of leasing system, but Congress moved slowly.

At the time, any hydroelectric project on federal land required a special-use permit or an act of Congress. From a utility’s perspective, a special-use permit from the Forest Service (who by World War I managed the land where roughly 50% of hydroelectric dams were located in the West) was too short to justify investment.1 So the mining of white coal moved more slowly than many western energy booms.

Not everyone was willing to wait.

Utah Power and Light Co. developed a hydroelectric plant in the Bear River Valley on national forest lands without permission. The company argued that since the Forest Service knew what the company was doing and didn’t stop it, then the utility should be allowed to continue its operation. In Utah Power & Light Co. v. United States (1917), the Supreme Court disagreed unanimously without breaking a sweat.

The decision prodded energy industries. They needed some sort of predictable order.

Breaking the Stalemate

Congress had been stalemated since Roosevelt’s time. Progressives wanted federal supervision of dam development and a fair return for the public’s resources. This would include some sort of compensation and a time limit. The Forest Service had proposed a 50-year license in 1907, but utility companies wished for an open-ended commitment and possessed sufficient power in Congress to stymie reform.2

While the logjam in Congress stalled change, the world went to war. Industry for wartime production increased electricity needs. Hydroelectric power in the long term was cheaper and would allow coal to be conserved for other uses.3

Enough impetus now existed for Congress to act and for the Progressives and utilities to compromise.

Law Passed

The Federal Water Power Act of 1920 (more often just called the Federal Power Act) established this new system. The law created the Federal Power Commission (since 1977, it’s been known as the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission) with the Secretaries of War, Agriculture, and Interior. The FPC could authorize up to 50-year licenses for dams on navigable streams as long as they did not interfere with the existing statutory purposes on the federal lands. Fees collected were distributed – half to the federal reclamation fund, 3/8 to the states, and 1/8 to the general federal treasury.

With the new system in place, that white coal soon would be mined. In the eight months after the law passed, applications came in for what amounted to 13 million horsepower. In the previous two decades, only 2.5 million horsepower were included. In the next three years, 21.5 million horsepower were tapped, while only 9 million existed anywhere before the law.4 The law unleashed American energy development.

Many observers see the Federal Water Power Act as the final piece of Progressive-Era natural resource legislation, even if some commentators identify it with too many compromises and weaknesses to be anything more than symbolic.5

Postscript

The licensing process is the easiest opportunity to challenge dams, but for most of its history, the Federal Power Act operated single-mindedly with a mission to build dams. Today, however, licensing and relicensing can pry open what once would have been impossible to imagine scenarios, such as removing dams.

The first time the FPC refused to authorize a dam license intersects with other research of mine. After a long, complex process, a conflict arrived at the Supreme Court. The details aren’t that important here, but the basic question concerned whether a dam proposed for Hells Canyon on the Idaho-Oregon border would be build by a private company or public utility. Justice William O. Douglas – the subject of my second book – wrote the Court’s 6 - 2 opinion. For the first time since its passage in 1920, the law stalled a dam; the Supreme Court stopped a license from being issued.6

Douglas pointed out that wildlife and fish conservation, as well as recreational needs, needed to be considered according to the Federal Power Act (and the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act of 1938). “The ecology of a river is different from the ecology of a reservoir built behind a dam,” he wrote, using “ecology” the first time in a Supreme Court opinion. Maybe, he suggested, the public interest would best be served by no dam at all. This was not a conclusion many had anticipated.

I’ll keep watching locally and continue my research staying alert to what unanticipated developments may come as the once-in-a-generation relicensing process continues for the Skagit River.

Closing Words

Later this spring, I’ll have a piece to share about the Skagit River, including some history and commentary about the dams. Meanwhile, you can read all about Justice Douglas and his environmental work in my work on him. The Environmental Justice includes the full treatment (and can be found through the Bookshop link below), but a brief overview of Douglas and conservation is available here, an adaptation of a talk I gave at the Supreme Court on the 75th anniversary of his appointment to the Court back in 2014.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

We’re swinging around to The Field Trip in the cycle next week. I always have ideas in mind, but sometimes unexpected opportunities emerge. Stay tuned to see where I go and what I report on!

As always, I’m grateful that you’re reading this. If you enjoyed it, press the Like button below or leave a Comment. If you know others who might enjoy this weekly newsletter, share it with them. And if you are able, consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Thank you for reading.

John D. Leshy, Our Common Ground: A History of America’s Public Lands (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021), 362; Samuel Trask Dana, Forest and Range Policy: Its Development in the United States (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1956), 366.

Samuel P. Hays, Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: The Progressive Conservation Movement, 1880-1920 (1959; New York: Atheneum, 1975), 81

Paul W. Hirt, The Wired Northwest: The History of Electric Power, 1870s-1970s (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2012), 175-78.

Dana, 367; Hirt, 177.

Hays 239-40; George Cameron Coggins, Charles F. Wilkinson, and John D. Leshy, Federal Public Land and Resources Law, 6th ed. (New York : Foundation Press, 2007), 533. The Progressives wanted a multipurpose water development law that would include not just power development but also flood control and irrigation.

Besides my own book, see Karl Boyd Brooks, Public Power, Private Dams: The Hells Canyon High Dam Controversy (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006), 220-22.

That's an amazing photo of the bridge across the Skagit. Wow.

The 1891 act allowing federal lands to be set aside were for 2 purposes, timber and watersheds of navigable rivers. The tonto was set aside to protect the watershed of the Salt river.