What Makes a Conservation Classic?

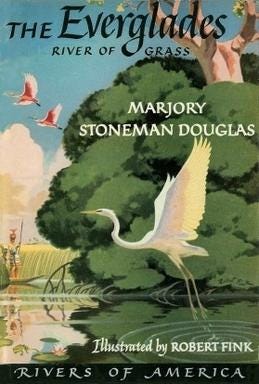

Reading Marjory Stoneman Douglas’s The Everglades: River of Grass

The source can be only the beginning in time and space, and the end is the future and the unknown. What we can know lies somewhere between.

Marjory Stoneman Douglas, The Everglades: River of Grass (1947)

When Marjory Stoneman Douglas wrote those words, she was contemplating how to write a history of the Everglades. History, she notes, moved like a river, constantly shifting. Finding the beginning or end of history, or of rivers, seldom was easy. We get glimpses only. The whole of time or nature can barely be grasped.

This timeless wisdom speaks directly to a writer interested in “place, history, and writing.” Read on!

Why This Book?

With hundreds of books left unread on my shelves, choosing one for The Library sometimes presents challenges. In most ways, Douglas’s book, The Everglades, sits comfortably within my comfort zone. It’s history. About conservation. Focused on a place where nature dominates. Written during the period that most fascinates me, the mid-20th century. But the Everglades are far, far from the places I know best and care about the most. Florida is another world away. Reading it as a sample of place-based writing in the conservation tradition brings rewards, though.

The Story

I came to The Everglades with expectations – which is always a mistake. I expected the book to be a conservation book, a story about the unique nature of the Everglades. I’d read excerpts before that primed my expectations along these lines. It is that. But more than a story of nature, this book is a history of a place. And it’s a substantial one, so I’ll be barely skimming the surface in this recap.

Nature

The beginning of The Everglades is the best part. Here, Douglas uses her considerable writerly gifts to paint pictures of this unusual ecology. She uses her evocative phrase “river of grass” to conjure this place as something biological and symbolic.

Where the grass and the water are there is the heart, the current, the meaning of the Everglades.

Douglas knows the Everglades will be foreign to most readers, so she spends time helping us think about it.

The whole system was like a set of scales on which the forces of the seasons, of the sun and the rains, the winds, the hurricanes, and the dewfalls, were balanced so that the life of the vast grass and all its encompassed and neighbor forms were kept secure.

More than once, Douglas deploys time metaphors. For an environmental historian, these are noticeable for their resonance with the entwining of nature and culture.

The life and death of the saw grass is only a moment of that flow in which time, the vastest river, carries us and all life forward. The water is timeless, forever new and eternal.

If I’d stopped reading after the first 40 pages, I would have imagined The Everglades as one of the most beautiful books of nature writing of the 20th century. Rich in symbolism, the book brings to life a place beyond my ken.

History

But the book doesn’t end after 40 pages; it goes on another 350, the bulk of it narrating a history of Florida.

Douglas writes well enough, but the long history of this place tired me somewhat. Maybe that is because in broad strokes, the history of the Everglades resembles the history of much of the continent: Indigenous peoples made rich lives since time immemorial; Europeans came and harrassed the local populations, which lasted a long time; piecemeal settlement followed by grander developments interspersed with local resistance and occasional disasters (e.g., hurricanes); eventual balance and stability seems achieved.

Of course, the details differ across different places, and those distinctions matter. That’s what a focus on place does – highlights the uniqueness among the broader patterns.

I closed the book thinking that the Everglades functioned in two ways through this century-long history. Often the Everglades served as an escape for Tribes and, later, for runaways seeking refuge from the slavers pursuing them. The Everglades did not appear welcoming to many of the first Europeans, so the river of grass became a site of freedom. As Douglas writes, “The Everglades still protected its own.”

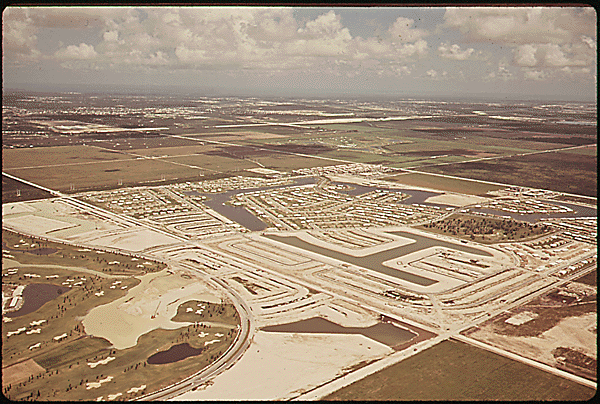

The second theme is the great process of draining the Everglades and turning the region into either farms or cities. The schemes were designed with little study or planning besides converting the river of grass to real estate fortunes. The ways enterprising people imagined this transformation changed by the generation. Most of the time, Douglas notes that “people were too busy boasting about the future . . .[to] work for it.” Eventually, though, enough momentum produced developments that changed the Everglades forever.

“Politics”

The landscape everywhere . . . is crammed with the bustle and energy of people making money in a hurry.

After so many generations of this behavior, the Everglades were in trouble. Douglas begins her final chapter with the simple message: “The Everglades were dying.” She explains how that had come to pass, noting how the river of grass became a “river of fire” after drainage and drought changed and wasted this unique resource.

At the very end, Douglas details how public opinion shifted toward an understanding that destroying the Everglades meant destroying everything. Instead, a national park was proposed with restoration its mission. A new balance would be achieved. No longer would greed reign. This was Douglas’s hopeful message to close out the book, which was published the same year the park was dedicated.

Addendum

Douglas’s faith – and many others’ too – in the Everglades future was not fully realized. She was in her late 50s when she published The Everglades but lived another 51 years! So Douglas witnessed continued and continual threats to the Everglades. Her optimism that the federal agencies would protect the unique of ecology proved misplaced, as the US Army Corps of Engineers devastated the land and waterscape. Development pressures and pollution, not to mention invasive species, plagued (and plague) the region. Topping it all, sea-level rise mocks everything.

Despite what may have been misplaced optimism, The Everglades helped Americans learn about this special place and do so with a greater sensitivity to its ecology. This was Douglas’s achievement in the book, putting this place into terms so that a low-lying “river of grass” appeared important enough to deserve the monumental protection “national park” conveys. In this way, it is a historic book, as well as a history book.

Final Words

Two weeks ago, I wrote about eastern federal lands, including the Everglades. You can find more context there, or in my book Making America’s Public Lands. Last week, I participated in a podcast with the New Books Network about that book. You can listen to it here.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

Next week, we close in on another Wild Card and, as is becoming a theme, I’m not quite sure what I’ll be doing. So, you’ll have to stay tuned!

As we move in the direction of summer, I’m making a push to increase my subscribers and the engagement with these Taking Bearings newsletters. So if you want to help with that, please press the Like button below or leave a Comment. If you know others who might enjoy this weekly newsletter, please share it with them. And if you are able, consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Thank you for reading.