Are Eastern Federal Lands Exceptional?

Adding Eastern National Forests and Parks to the Public Land System

Looking back at these newsletters, I see a lot of new topics and places, things I’m trying to learn about. This week, returning to The Classroom, I’m revisiting a subject – public lands – that is more familiar to me. My angle is how the public land system incorporated places in the East. As a bonus, this should offer some context for a newsletter I’m planning in the near future. Read on!

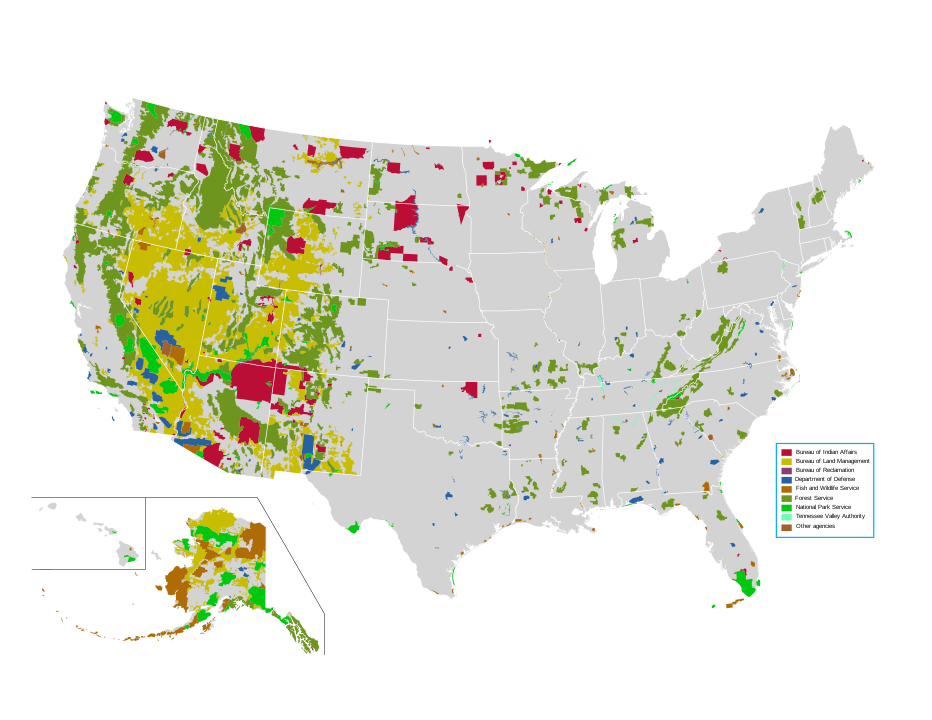

Public Lands in the West

Glance at the map above showing federal lands in various colors, all bunching up in the West. The federal government protected the first national parks and national forests and national monuments in the West. History, infused with ecology and politics, explains this regional dominance.

Since the earliest days of the republic, the nation focused on turning Indigenous lands into private property. The process proceeded rapidly. The continent is large, though, so it took time for people to claim these lands through the Homestead Act and similar laws. By the 1870s, voices in and out of government spoke of alternatives.

Some places were too dry. Some places were too high. Some places would not support a paying farm much less any sort of manufacturing center. Other places offered such magnificent scenery that some Americans thought they should be available to everyone, not locked behind a Private Property sign. The story is much more complicated of course, but these factors and ideas brought forward the roots of the public land system – a set of land that would remain in government hands in perpetuity.

In the US West, millions and millions of acres remained unowned. So when the idea of creating a forest reserve or a national park emerged, government land could be marked as “off limits.” The federal government did not need to buy the land; they already controlled it. This is the simplest reason so many federal lands remain in the West.

The Counterpoints in the East

The East offered alternative paths for public lands. Ecological conditions (e.g., deserts and slopes in the West are much more severe) and the ownership patterns (e.g., far, far less land owned by the federal government) made the East different from the West. However, reform ideas about better forestry and a desire for recreational and scenic lands remained consistent across the regions. And the desire to create a truly national public land system pushed advocates toward eastern landscapes, too.

Creating Eastern National Forests

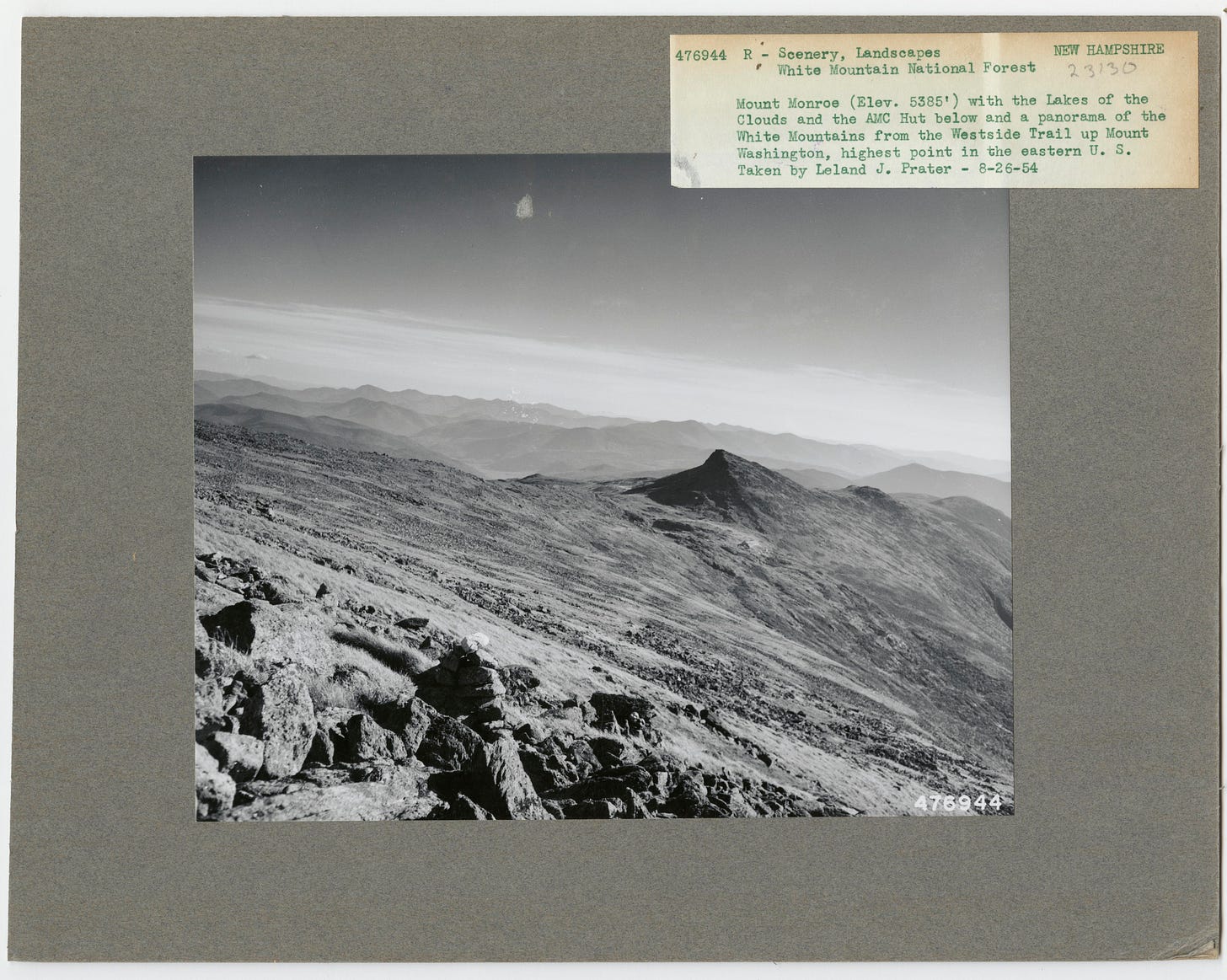

Conservation ideas did not reside only west of the Plains. The 19th-century man most alarmed about deforestation hailed from Vermont (George Perkins Marsh). Virtually all the leading figures in the forestry movement that emerged in the late 19th century came from eastern states. From North Carolina’s Appalachian Mountains north to New Hampshire’s White Mountains, forests faced rapacious logging and frequent fires that put long-term community and ecological sustainability at risk.

Political ideology and the reigning legal interpretations from the Supreme Court made it difficult for the federal government to regulate private property. But energy developed to change that or find ways around it. States like New York and Pennsylvania acquired land and create parks and preserves. Southern states – bastions of states’ rights – even passed legislation to authorize the federal government to buy forest land within their borders. Congress moved slowly.

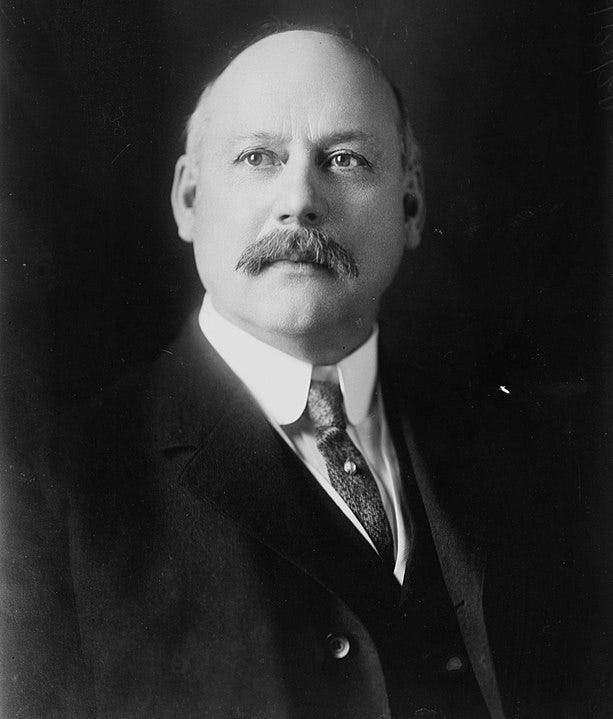

Speaker of the House Joseph Cannon (R-IL) referred to forestry as a “fad” and characterized people promoting it as “nuts.” Not just antagonistic to modest forestry reforms, he also proclaimed, “Not one cent for scenery!” Getting a forestry bill through his House of Representatives would not be easy.

Help came from nature and reformers. In 1907, the Monongahela River flooded in West Virginia and Pennsylvania causing $100 million in damages. A local newspaper pointed out that two decades before two inches of rain would have increased the river’s size but not flooded the landscape so badly. Logging was to blame: “The barren hillsides are responsible for it.” So, floods (also fires) pushed action.

Meanwhile, local organizations that included ministers and doctors and middle-class women toured the region to champion parks and trails, as well as to call for forest conservation. Their energy built popular momentum that helped move congressional leaders.

In 1910, the Weeks Act moved through the House with a little room to spare. Idaho Senator Weldon Heyburn, a fierce opponent of the Forest Service, called it the “most radical piece of fancy legislation” that ever appeared in the Senate. Meanwhile, his state burned with the massive 1910 fires, helping to spark support. In early 1911, the Senate passed it and President William Howard Taft signed the law on March 1.

The Weeks Act focused explicitly on watersheds of navigable streams (see, the floods were important!). It allowed the federal government to acquire lands to conserve forests to help protect streams. Within a decade, the Forest Service managed more than two million acres in the East. It was not coercive. Most of those lands came from cutover lands, places harvested and abandoned and often left tax delinquent. In addition, the Weeks Act also supplied funds for states that developed fire protection plans withing federal guidelines (see, the fires were important, too!).

How did these eastern national forests compare with western ones? They were distinct in the sense that they originated as private (or abandoned) lands. They also frequently were brutalized landscapes that required rehabilitation, while in the West, most reserved forests were meant to be protected and thus not require rehabilitation. In this way, the East helped lead the agency toward restoration work. Of course, this took time.

Building out the National Parks System

The same ownership pattern existed for national parks, so the federal government needed to figure out ways to acquire land for national parks. The social networks created to promote scenic preservation and forest conservation built momentum and found places worthy of protection as parks. This took time and followed multiple paths.

The first eastern national park, Acadia, started as a private retreat for the wealthy called Mount Desert Island. Two residents created a trust and began acquiring land. In 1916, they amassed five thousand acres and gave it to the federal government, and President Woodrow Wilson created the Sieur de Monts National Monument. Later, John D. Rockefeller Jr. donated $3.5 million to the trust, allowing the acreage to quadruple. Finally in 1919, Congress changed the name and status: Lafayette National Park. (A decade later the name changed to Acadia.)

The National Park Service then turned south, but obstacles prevented easy acquisition. Congress authorized three new parks in the South: Mammoth Cave (Kentucky), Shenandoah Mountains (Virginia), and Great Smoky Mountains (North Carolina and Tennessee). A catch, though: Congress prohibited the federal government from purchasing any land; philanthropists or states needed to acquire and donate the land. Meanwhile, Congress authorized another southern park, Everglades, in 1934. In all these cases, it took more than a decade from park authorization to park dedication.

One reason for these delays was people lived within the park’s boundaries. (This was true of many of the West’s national parks, too, but less often commented on.) Creating the Smoky Mountains park led to buying up more than 1,100 small farms and 18 large land tracts and removing something like 5,665 people. Once again, Rockefeller money helped fill park acquisition funds.

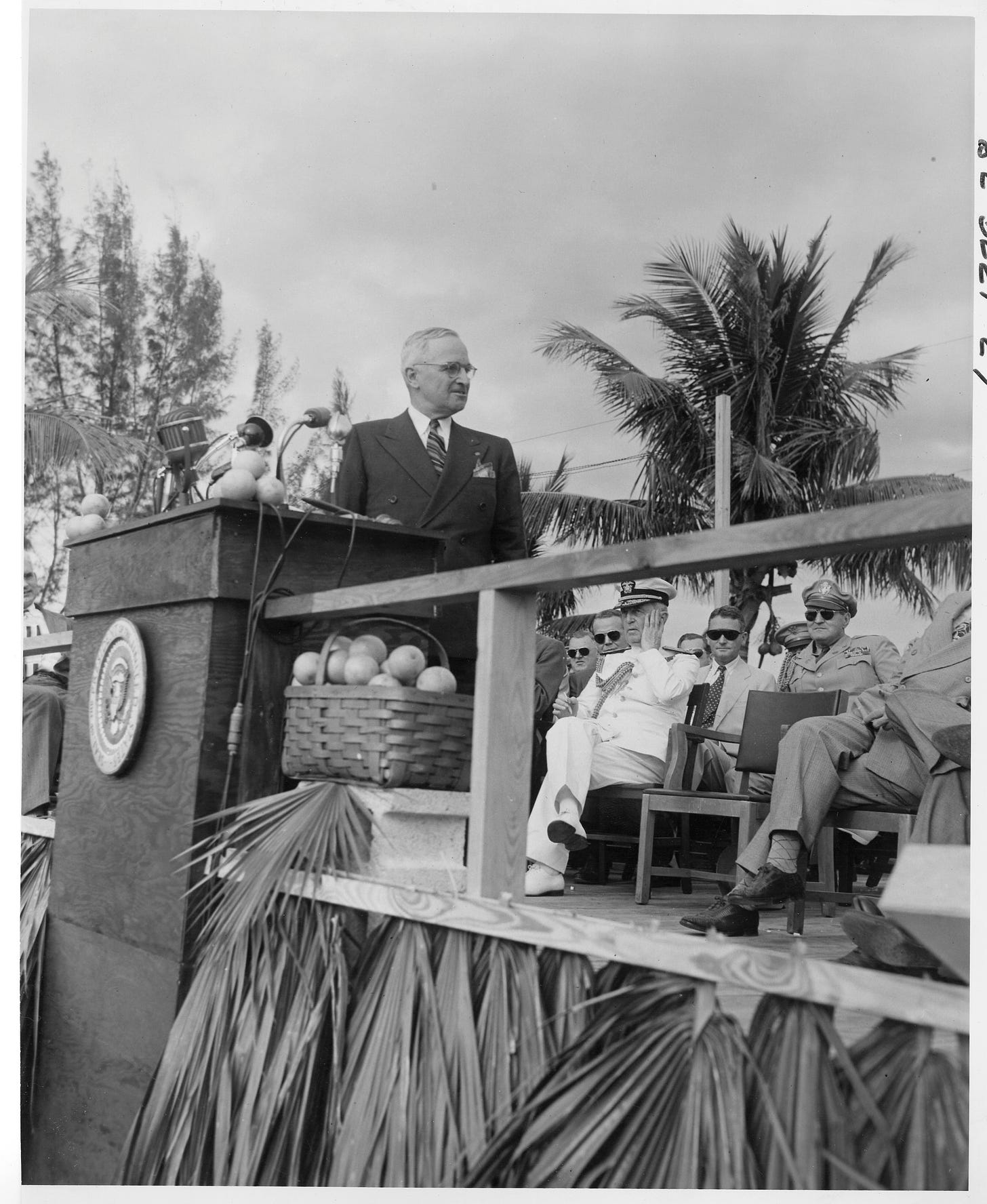

Further south, in Florida, the Everglades presented unique elements. Natives peoples lived within the park. Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes suggested in a 1935 radio address that “the Seminoles ought to have the right of subsistence hunting and fishing within the proposed park,” something he thought might “in some degree, make up for the sufferings” at the hand of the United States. In the end, and perhaps not surprisingly, relocation, rather than incorporating these rights, became the policy.

Another unique part of Everglades history was the need to rethink scenic grandeur. Most previous parks seemed monumental – consider the sheer walls in Yosemite, the giant chasm of Grand Canyon, the hulking dome of Mount Rainier – but the Everglades “towered” a mere eight feet above sea level. A congressional opponent of the park called it a “snake swamp park on perfectly worthless land.” Something of a cultural revolution was necessary to help the public understand the Everglades’ ecological value. Although she was not alone, Margory Stoneman Douglas helped transform the Everglades’ image with her 1947 book The Everglades: River of Grass through which she helped people come to appreciate this unique ecology. For the first time, a park seemed selected for what we might call ecological values.

Alternative?

Were the eastern forests and parks alternatives or fully consistent with the public lands system? It’s a trick question in part. The public land system, like all political systems, evolves, so any change helps create its character. What the eastern add-ons helped do, though, was to increase the system’s capacity for rehabilitating lands and working with private owners. Neither case, it’s worth emphasizing, has been perfected.

Closing Words

I’ve adapted this newsletter from my most recent book, Making America’s Public Lands. You can find a bibliographic essay there for guidance on my sources.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

The Field Trip is up next week, and I’ll need to either get out to a new place or dig up some recollections. I’ve not committed yet. Stay tuned!

If you enjoyed this newsletter, press the Like button below or leave a Comment. If you know others who might enjoy this weekly newsletter, share it with them. And if you are able, consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Thank you for reading.