The Americans of all nations at any time upon the earth have probably the fullest poetical nature. The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem.

I’m not certain Walt Whitman is correct in this sentiment, taken from his introduction to his first edition of Leaves of Grass (1855), but I’ll take his judgment under advisement.

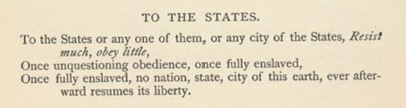

In the blustery autumn days, when the American election season winds down (and the aftermath ramps up), it can be hard to pause and hear poetry. At a time when candidates, journalists, and writers warn of the nation’s deepening divisions and point to (and at times stoke) civic disorder, Whitman’s essentially optimistic vision seems to require thick spectacles.

The nation’s collective verses seem blunt (and often too hateful) to be poetical.

Still, for The Library this week, I’m turning to poetry — something far from my comfort zone — to see if I can locate wisdom. As a small-d democrat, Whitman seemed like the place to start. Read on!

Whitman and the “Common People”

A few lines beneath those quoted above is Whitman’s statement that the United States “is not merely a nation but a teeming nation of nations.” One of my first college history textbooks used that — Nation of Nations — as its title. Despite that long link to a few of Whitman’s words, I’m not well-versed (excuse the pun) in his work.

Dipping into it can be an experience of disorientation. It is not so much that his language, 170 years old, is difficult, but because Whitman exudes an exuberance that is uncontainable. His enthusiasm, especially for the nation, enlivens seemingly every page beyond the point of familiarity or even comprehension.

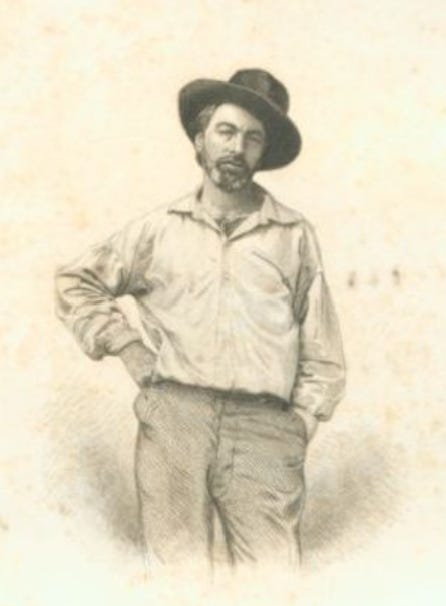

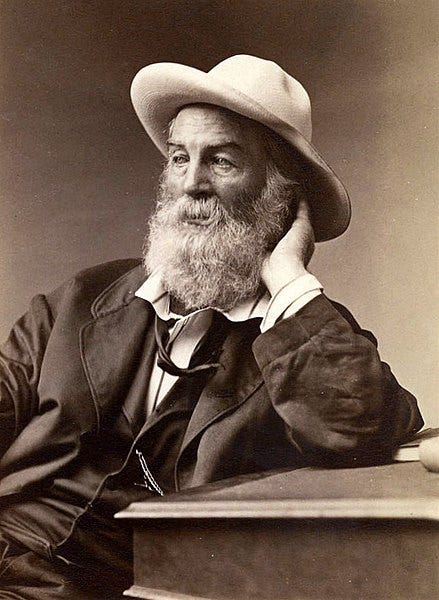

His biography put him among what he called the “common people,” and his disposition made him praise democracy. During the Civil War, he visited wounded soldiers and understood the war’s causes and costs more intimately than many.

In “For You O Democracy,” composed first in 1860 and revised seven years later, Whitman wrote of “the continent indissoluble” before celebrating the camaraderie among Americans he hoped would prevail. From the vantage point of 1867, the continent may have appeared indissoluble, but only narrowly. A four-year war with more than 600,000 dead had severely tested that proposition.

The only way the nation might last, Whitman suggested, would be finding some common feeling — something that may have still seemed possible in 1867.

As was his wont, Whitman pulled from the natural world:

I will plant companionship thick as trees along all the rivers of America, and along the shores of the great lakes, and all over the prairies

I will make inseparable cities with their arms about each other’s necks,

By the love of comrades,

By the manly love of comrades.

You need not have a PhD in American history to realize that Whitman’s hoped-for comradeship failed to materialize. The hope of national reconciliation after the Civil War dissolved in a cauldron of racial violence, the consequences of which we still live with.

The Welcoming Democrat

Although he occasionally wrote about themes of slavery and freedom (from a vaguely anti-slavery perspective), Whitman more commonly focused on class. Rather, he saw the nation as composed of many people — a teeming nation of nations — and how the United States offered classless possibilities.

“I Hear America Signing,” a poem contemporaneous with “For You O Democracy,” opens with this characteristic feeling:

I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear

Then, he proceeded to go through several occupations — mechanics, carpenters, masons, and so on — suggesting either a working-class, or a classless, vibrancy alive in the nation. Each person, he said, is “singing what belongs to him or her and to none else.” Glimpsed here, I think, are two American themes, opportunity and individuality. Each individual might own things.

But that might be too narrow. Belonging, after all, transcends mere ownership. As we imagine an opportunity economy, may we also imagine a civil society that embraces belonging as something widely available and not purchased or inherited, something truly democratic.

[The preceding paragraph was written before election results were apparent. Read in the harsh light of reality, it reads as hopelessly naive. A belonging open to all is not what a majority of voting Americans seem to want.]

Complacent No More

Across the last decade, American politics has felt like a greater ordeal than it did earlier in my life. Stakes have been high in both real and imagined ways. Just yesterday I saw a New Yorker story about “The Americans Prepping for a Second Civil War” suggesting how worked up many feel. Few of us, it seems, were prepared for having the nature of these divisions revealed — and revealed again.

Americans had become complacent.

Whitman understood complacency, too, and perhaps the ways it intersected with what we call American exceptionalism.

He wrote “Long, Too Long America” in 1865 and revised it in 1881. The poem warns the nation of complacency. For too long, Whitman explained, Americans knew peace, joy, and prosperity (i.e., that exceptionalism). But the war shook foundations. Now, the nation needed “to learn from crises of anguish, advancing, grappling with direst fate and recoiling not.” Like we must do today, Whitman urged readers then to heed the anguish, to face it. Don’t shirk your duty, Whitman said, for we must “conceive and show to the world” what the nation is really like.

I expect that Whitman, were he to observe the country in the 21st century (and perhaps on this day in particular), would wonder about what the nation has shown the world.

Looking Ahead

In an 1888 poem, simply titled “America,” Whitman found his footing again, optimistic, equality-focused, rooted in solidity.

Centre of equal daughters, equal sons,

All, all alike endear’d, grown, ungrown, young or old,

Strong, ample, fair, enduring, capable, rich,

Perennial with the Earth, with Freedom, Law and Love,

A grand, sane, towering, seated Mother,

Chair’d in the adamant of Time.

Sit with that poem for a moment. Is this what we want? Is this what we are?

I enjoy Whitman’s imagery here and especially the connection between the persistence of the Earth and its equivalence with freedom, with law, with love.

May it be so. Someday.

Post-script

I wrote this newsletter before election day ended. I didn’t expect a definitive answer by the time it was scheduled to go out. I was wrong.

Still, regardless of how it turned out, I’d already seen enough in the last decade to know more than I knew before about our fellow citizens. The mask had been ripped off again and again. On many, if not most, days, I struggle to channel what I take to be Whitman’s basic optimism. I especially struggle when I’m mired in news reports and social media feeds.

Out among real people, the “common people,” performing their real lives and not for a camera or clicks, my optimism usually returns. But it must be practiced, just like democracy.

Closing Words

Relevant Reruns

Perhaps one of Whitman’s contemporaries, Thoreau, is worth reading about again in this old newsletter. I wrote a short essay in Talking River Review, almost a prose poem, a few years ago that ultimately asks us to consider how others see us. Maybe it is worth thinking about now.

New Writing

Several weeks ago, I wrote a newsletter about the First World Conference on National Parks. I wrote something else on that topic, now available at HistoryLink.org.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

We return to The Wild Card next week. Surely something wild will come our way in the next week. Stay tuned!

Thanks for your mention of Whitman and his poetry. And about the mask being ripped off. The varied carols of hate and division and anger are now getting a strong boost. Those singers thrive on lies, false promises, and bully techniques. But we have to believe in another way. Poetry has a lot to offer in that regard.

Thank you, friend. I too turning to poetry and poets now. Holding complex feelings at once that don’t seem like they should be held at once is needed now and is what poetry does.