Before I start this week’s newsletter, please allow me to make an appeal and an offer.

August marks two years of Taking Bearings, two years of weekly thoughts and lessons about place, history, and writing. I am hoping to increase subscribers and would be grateful if you shared this newsletter with a friend or family member you think would enjoy it. I’ve turned on a referral program. After four referrals, you will be comped free access to paid content for a month (and the rewards increase with more referrals).

I’m also asking that current free subscribers consider upgrading to the paid option. To celebrate this two-year anniversary, I am offering a discounted subscription rate. I intended this to be for July, but I’m extending it one more week, through August 7.

Thank you for your consideration. ~Adam

For another writing project I’m engaged with, I’ve been thinking about James G. Swan, a significant figure on the 19th-century Northwest Coast, especially Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. I could spend the next several years researching him and not exhaust all there is to say — an impracticable task since I’m not writing his biography.

But for a taste, I’m using The Classroom this week to introduce Swan and reflect on some of what he represents and the ambivalence I found in him as a historical figure. Read on!

Brief Biography

Swan was born in Massachusetts in 1818, the same year the United States and England agreed to jointly occupy Oregon Country. Men in Swan’s family took to the sea — and the sea took his father when he was five — and inspired him to long for adventures, too.

Like many similar men did, Swan left his wife and two children in 1850 for California. After two years working in San Francisco, Swan headed north to Shoalwater Bay, known now as Willapa Bay. Using the Oregon Donation Land Act, he took out a homestead claim and lived there for three years. He wrote about it in one of the earliest books published about the region, The Northwest Coast, Or, Three Years’ Residence in Washington Territory.

He left Washington for a few years, living in Washington, DC, before returning to the Northwest. For the rest of his life he lived on the Olympic Peninsula, bouncing between Port Townsend to Neah Bay more than once. He died just as the 20th century started on May 18, 1900.

Coming into a Fluid Place

Through those years, Swan kept himself busy. The entry on him at HistoryLink.org described his work as “an oysterman, customs inspector, secretary to congressional delegate Isaac Stevens, journalist, reservation schoolteacher, lawyer, judge, school superintendent, railroad promoter, natural historian, and ethnographer.”

The writer Ivan Doig, in Winter Brothers, adopted a similar list: “oyster entrepreneur, schoolteacher, railroad speculator, amateur ethnologist, lawyer, judge, homesteader, linguist, ship’s outfitter, explorer, customs collector, author, small-town bureaucrat, artist, clerk.”1

It’s easy to skip over lists like that, I know, but don’t skim. Pause and think for a moment what those labels suggest about Swan and the world he inhabited.

To me, they suggest that Swan was curious and creative about nature and culture. He was entrepreneurial and a promoter. He enjoyed learning and teaching (if not always in a classroom). He could organize and order people and things and information.

And the world Swan operated in must have been a fluid place, a society that encouraged or at least allowed people to try new things and constantly define and redefine themselves. It must have been a place where officialdom was being created and imposed on what governments found to be somewhat chaotic. (It is important always to remember that thousands of people functioned fine since time immemorial without customs collectors or school superintendents.)

Given how much of Swan’s work was marketing in one form or another, it must have been a place where a certain kind of opportunity seemed available, even irresistible.

Throughout the American West in the 19th century you could find characters like Swan in many places. They arrived restless and determined, aiming to replace what existed and build a future.

We are taught to admire this, and much is admirable.

However, at the root of so much of it is displacement, replacement, a rejection of who and what already occupied the Northwest Coast. There is less to admire in this.

Ambivalence

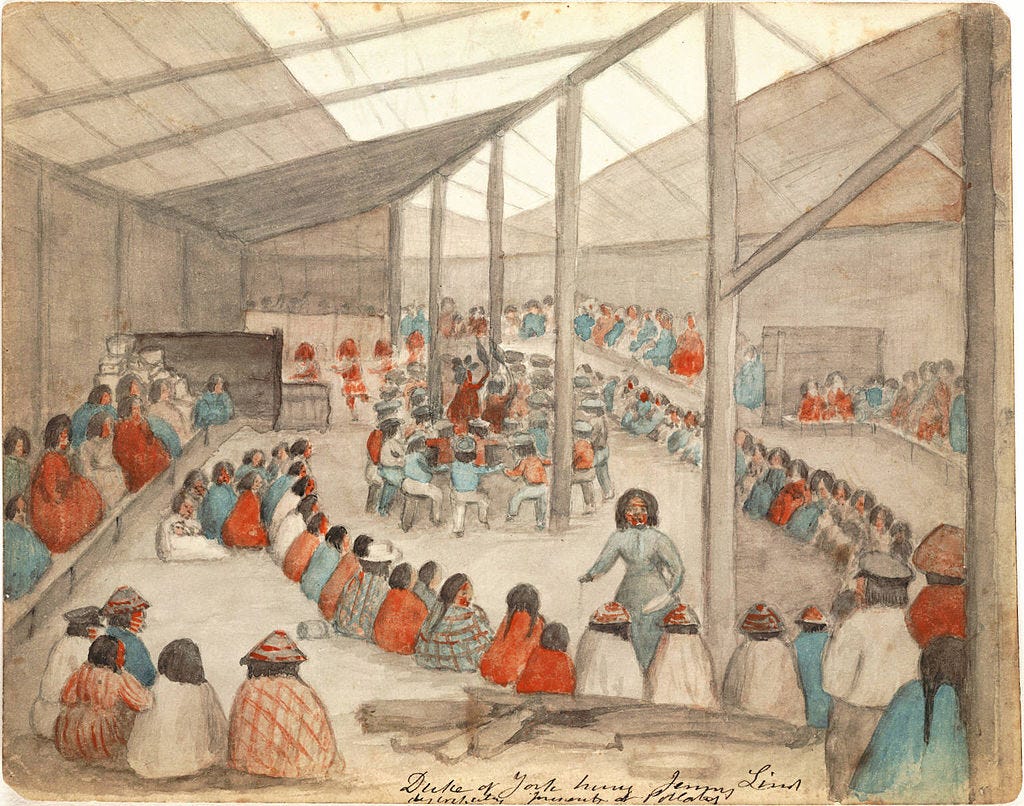

One thing that brought Swan some renown was his ethnographic work and collecting. And nowhere is the ambivalence of someone like Swan more on display — in his time and especially as we look back from our own — than in activities like that.

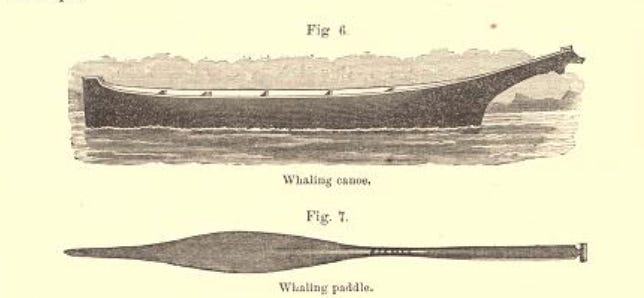

Swan lived beside and among various Indigenous groups for many years, especially the Makah. Living at Neah Bay for more than one stretch, he learned about daily life and expressed curiosity about customs. He wrote it down in The Indians of Cape Flattery, at the Entrance of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Washington Territory (1868) for the Smithsonian Institution. He also collected material, some of which he purchased, but I have not tracked down how much was purchased and under what circumstances or how much was pilfered, sacreligiously.

Assumptions drove the interest in ethnography at this time. The main one being that Native peoples would soon disappear or be assimilated so much that their culture would vanish. Swan certainly expected something like this and was aware, to some degree, the he was part of the cutting edge to do this work. He once wrote, “We have indeed caused the plowshare of civilization to pass over the graves of their ancestors and open to the light the remains of ancient lodge fires.”2

With that obvious awareness it is tempting to question Swan, to wish him to act differently, to shake him awake to the offensive use of “savages” that found their way through his pen. He seemed close, sometimes, to understanding the forces being unleashed by the American government and citizens.

Early on, while still homesteading at Shoalwater Bay, Swan participated in a treaty-making episode. (It is recounted in The Northwest Coast, beginning here; and it is excerpted and available easily here.) Even at a glance, the account is interesting, full of details and anecdotes.

Given who Swan was when the book was published in 1857 and given the prevailing attitudes among American society, you would expect him to favor treaties (especially if you knew that Swan soon went to work as Governor Stevens’s personal secretary). Yet even here, even before Swan had long experience with tribes in the region, he knew something was off.

Swan’s description of the treaty negotiations emphasized the Chinook jargon used to translate through at least three languages was “at best is but a poor medium of conveying intelligence.” Swan accepted that treaties were necessary and he said that the groups gathered accepted that a land purchase was necessary — and acceptable. What was not acceptable, Swan conveyed, was large reservations on which several groups would be gathered.

Swan quoted someone he identified as Narkarty, a Chinook chief:

We are willing to sell our land, but we do not want to go away from our homes. Our fathers, and mothers, and ancestors are buried there, and by them we wish to bury our dead and be buried ourselves. We wish, therefore, each to have a place on our own land where we can live, and you may have the rest; but we can’t go to the north among the other tribes. We are not friends, and if we went together we should fight, and soon we would all be killed.

Two sentences later Swan said Stevens “certainly erred in judgment.”3

Swan could see some of this, empathize with some of these shortcomings, and also not fully understand. This kind of ambivalence — on the white side of the frontier at least — was more common than we sometimes think. That doesn’t mean that Swan and men like him deserve unalloyed praise. But support for how history unfolded did not approach unanimity as it was unfolding.

True Occupation; Missed Opportunity

Swan’s true occupation, according to Doig, was a diarist. He left journals of four decades, some 2.5 million words. But, if Doig is to be believed, not a lot of it contained introspection. As much as Swan observed, you can be forgiven for wanting him to spend some of that writing to observe himself.

Closing Words

Relevant Reruns

A very early newsletter discussed treaties and is somewhat relevant here. For another character out of the 19th and early 20th century, check out this article I wrote about Ralph Cameron, an Arizonan who dipped his fingers into a lot of things.

New Writing

New things coming soon!

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

I welcome The Field Trip’s return next week. Stay tuned!

Ivan Doig, Winter Brothers: A Season at the Edge of America (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980), 4.

Doig, 91.

The treaty negotiations broke down, and only the Quinault signed.

Yes, Winter Brothers is a beautiful book, strange and incredibly creative. I have a quote from it above my desk.

Winter Brothers!