Surveying John Muir Surveying Western Parks and Forests

Revisiting a Muir essay to see if it stands the test of time?

I cut my environmental historian’s teeth on John Muir when I was a college student. I have rarely revisited his writing in the decades since, so for The Library this week, I thought it was time to check in again. How does Muir stand the passage of time? Read on!

Muir in Historical and Personal Contexts

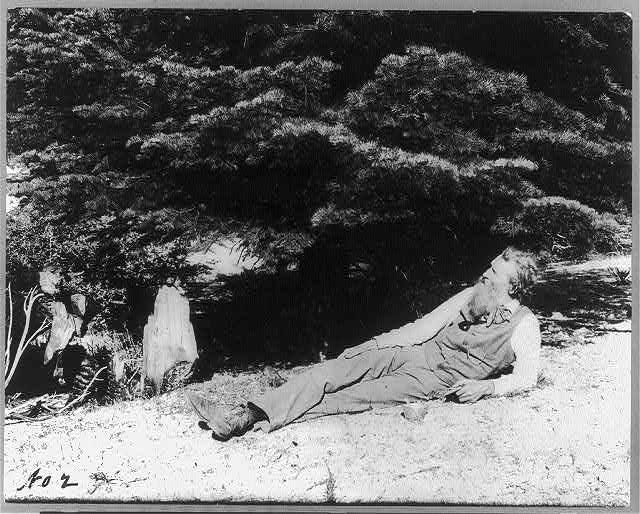

Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity; and that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life.

—John Muir, 1898

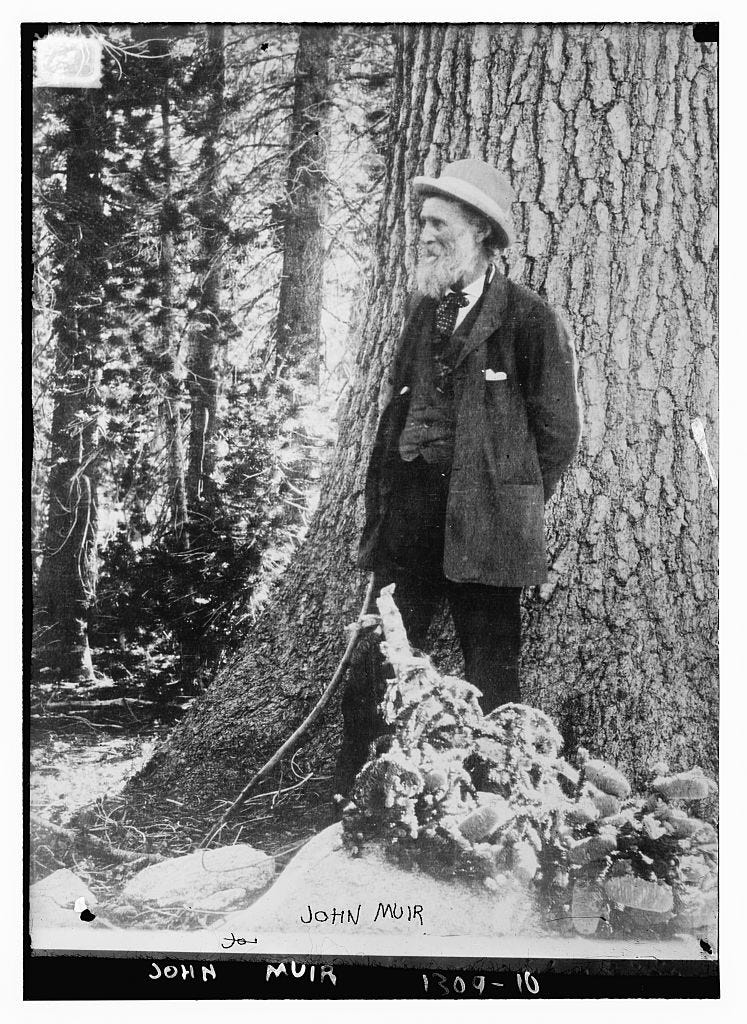

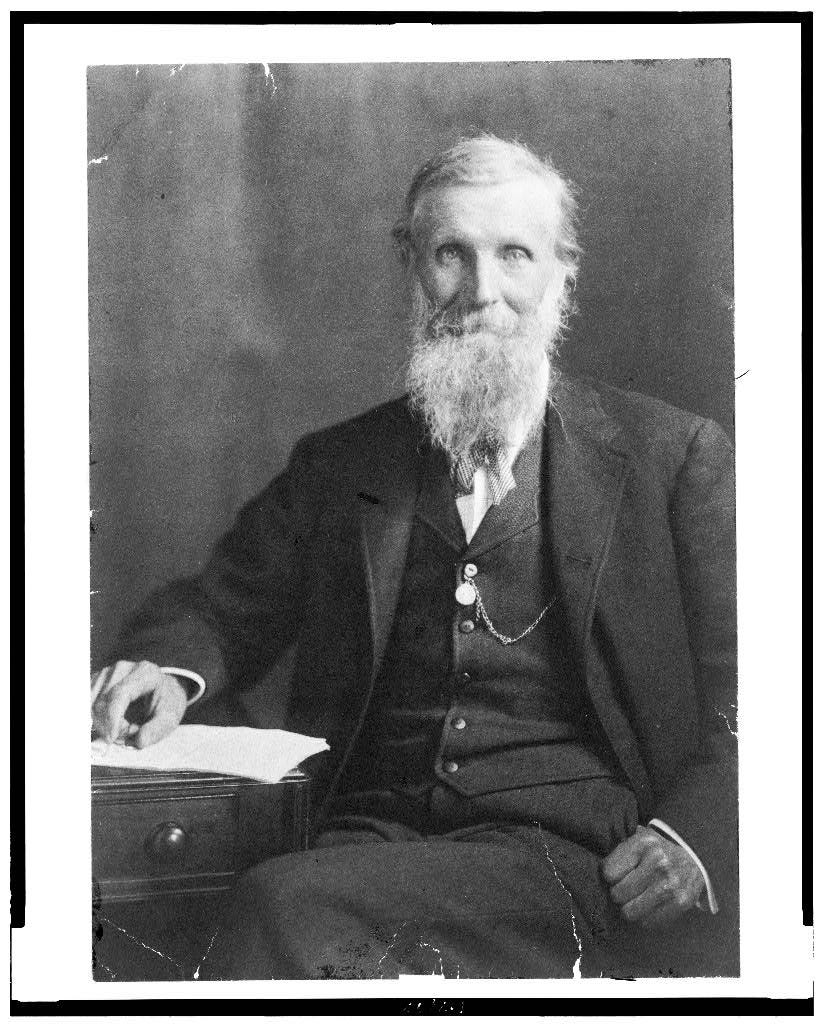

Few lines are more familiar to those who buy coffee table books with photos of big trees, tall waterfalls, and grizzly bears. John Muir made a specialty of capturing the natural world’s grandeur in memorable phrases. That is partly why this Scottish immigrant born in 1838 remains well-known, and often relevant, in 2023.

The words above are the second sentence of an article Muir published in The Atlantic Monthly in January 1898 and later repackaged as the opening chapter in his 1901 book, Our National Parks. The essay, “The Wild Parks and Forest Reservations of the West,” was one of Muir’s attempts to capture an overview of the federally-protected lands in the West.

In 1896, he joined (unofficially) the National Forest Commission that investigated western forests with the aim to make recommendations to the federal government about what it ought to do with them. Muir did not officially join the commission because he wanted to feel free to conclude and advocate whatever he wanted and not be bound by official pronouncements.

The commission urged federal protection of forests, which mainly meant preventing individuals or companies from homesteading or buying them. After receiving the report, President Grover Cleveland reserved thirteen more forests reserves (what we now call national forests), constituting more than 21 million acres. (Presidents had held the power to do this only since 1891.)

In addition, Congress could create national parks, the first being created in 1872 with three more added by the time Muir wrote his article. This conservation situation was fluid—so fluid in fact that another national park (Mount Rainier) was created between the time Muir published his article and when it appeared in the subsequent book.

I chose this essay out of many Muir possibilities because it bookends my academic work. My first serious academic research conducted during the summer before my senior year of college focused on Muir; my last serious academic research resulted in a history of the public lands. This essay encapsulates the whole sweep of my scholarship.

“The Wild Parks and Forest Reservations of the West”

Muir’s essay is an argument followed by a survey where he embeds enough details to persuade readers. Theoretically.

Muir claimed that some humans work too hard and some succumb to the “deadly apathy of luxury.” Living in cities especially denied people the rejuvenating effects of nature (usually “Nature” from Muir’s pen). Outside cities, “the clearing, trampling work of civilization” by the “spoilers” threatened to destroy the continent. The public ought to be aroused to support the government’s protection of the forests and parks against such work and insist on even stronger measures.1 With proper protection, Muir maintained, these places would be available for visits, “getting in touch with the nerves of Mother Earth.” And that’s precisely what people should do.

This all was a political argument, not simply “nature writing.”

The survey offered next in the piece is more like traditional nature writing. Muir traced a route around the West, from Alaska to the Black Hills of South Dakota and then counterclockwise to the Northern Rockies, then the Pacific Northwest, south to the Sierras, and ending at the Grand Canyon. Along the way, he highlighted species of what he termed plant people and animal people. Much of it is fairly straightforward.

But some of it sings, such as this bit describing what was then the Flathead Reserve and now is Glacier National Park:

Give a month at least to this precious reserve. The time will not be taken from the sum of your life. Instead of shortening, it will definitely lengthen it and make you truly immortal. Nevermore will time seem short or long, and cares will never again fall heavily on you, but gently and kindly as gifts from heaven.

Muir’s survey intended to entice visitors. Throughout, he encouraged tourists to get into the mountains that he described superbly. His survey also meant to explain why only vigorous protection can keep these “gifts from heaven” from being tainted or destroyed by sin. He cited the effectiveness of soldiers guarding national parks (this was prior to the National Park Service’s founding) and believed the public would demand this if it knew these glorious places:

If every citizen could take one walk through this reserve, there would be no more trouble about its care; for only in darkness does vandalism flourish.

(From the vantage of 2023, I fear vandalism flourishes out in the open, too!)

A Capsule of Time

“The Wild Parks and Forest Reservations of the West” is not Muir’s most famous writing, but it’s a useful one for sampling his approach. The argument he makes and the quality of his survey approximates what I recall from my much more extensive reading of him in the mid-1990s. And it does a nice job capturing the emerging conservation moment as the public land system began forming.

In recent years, the environmental community has reassessed—and sometimes criticized—its history, including the positions of some of its founders, including Muir. An excellent place to catch up on this discussion is Michelle Nijhuis’s article in The Atlantic, "Don’t Cancel John Muir: But Don’t Excuse Him Either.’

Muir’s anti-urban perspective can be equated to an anti-immigrant and elitist one; his emphasis on “cleanliness” has been associated with racism.2 But he has been most criticized, I think, for some of his writings on Indigenous peoples and African Americans. In this essay, there is nothing connected to the latter, but the former is evident briefly. Muir erases/diminishes Native presence in the landscapes he celebrated, a common sin of omission. He also relied on stereotypically offensive language (e.g., “savages,” uncivilized). Maybe the worst, though, is reading Native peoples as being virtually all dead, consigning them to the past and not the present or future. Such language and erasures surely were common at the turn of the 20th century, but that does not mean we should skip over it without registering its factual inaccuracies, offensiveness, and dangerous implications.

Becoming attuned to the details in the natural world enriches our experiences. Being attuned to the details in the written word also deepens our understanding and tempers unexamined legacies. Revisiting “classics” and things we appreciated decades ago is good practice in testing the supposed longevity of ideas.

Closing Words

You can find a copy of my work on John Muir here; by date, it is my second professional publication, but in reality, it was my first. I have a few new publications to report. Last week, a piece of reporting on reintroducing grizzly bears in the North Cascade appeared here. This week, a new personal essay of mine—called “War and Geese”—appeared in Wild Roof Journal here (or here). I hope you’ll consider reading these pieces.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

We round on The Wild Card next week. Also, paid subscribers will have access to a new interview with the prize-winning nature writer Marina Richie. Stay tuned!

In fact, between the article’s publication and the book chapter, national parks increased from four to five and forest reserves increased from 30 to 38, and more government officials had been hired and placed in the field—improvements Muir noted in the book’s footnotes.

Although he does not examine Muir, Carl A. Zimring’s Clean and White: A History of Environmental Racism (New York: New York University Press, 2015) makes this argument effectively.