For The Field Trip this time, I intended a more urban setting, Anacortes. This is a local town that takes advantage of being surrounded by water. It has a distinct maritime and tourist feel, and I intended to sample it on a quiet weekend morning. Instead, I ended up reflecting on dangerous work. Read on!

Complicated Identity

Sometime in childhood, my parents took me to some sort of arts festival on the streets of Anacortes. The memories are hazy, but I remember walking a long way and being hot. I revisited that town for other occasions—catching ferries to the San Juan Islands or Victoria, British Columbia; dinner before prom; catching a boat with my dad to go fishing with his brother for a couple days during which a pod of orcas surrounded our small boat.

Now, I live about half an hour away from the town and head there periodically—sometimes for reporting, sometimes for shopping, sometimes simply for its views. I do not know the town’s secrets, despite these return visits, but it intrigues me and I learn something new on each trip.

The town rests on the northern tip of Fidalgo Island at the western edge of Skagit County. Its population reaches toward 20,000. Because of the ferry that leads to many vacation spots and perhaps that arts festival, I always think of it as a tourist town. However, it is a more complicated place.

There is a strong industrial history that partly continues. Timber mills and shipbuilding and commercial canneries have left their marks. Across a small bay on a peninsula are oil refineries that have been in place since the 1950s. I can see their exhaust from home, a reminder of the fossil fuel ties we depend on. From town, magnificent views of the Cascade Mountains can be juxtaposed by the engineering of the refinery.

Juxtaposition

That kind of juxtaposition is common there.

After my spouse and I started the day with breakfast at a local favorite restaurant and meandered through the farmers market, we headed along the marina. I aimed us toward a green spot on a map that I noticed.

Along the way, we were surprised by a small memorial park dedicated to the memory of two crabbing crews lost at sea on Valentine’s Day, 1983. The Altair and Americus were built in and crewed from Anacortes. They both sank in calm waters in the Bering Sea. Seven men on each boat died.

We walked on, along the marina boardwalk.

I worked at a marina during the summers at the end of high school and early college, helping people fuel their boats. Marinas reveal social in interesting ways. Some truly enormous yachts were moored there, reflecting a type of wealth that I find disconcerting. Some modest craft were there, too, representing different kinds of dreams of sea independence. Small and large fishing boats also floated in their slips, marking a type of economy quite different from that embodied in the yachts.

On public pathways along the shore, the city has fashioned garbage and recycling cans as replicas of old canned salmon tins, a reminder of a cannery past and a time with a capital-intensive and environmentally destructive industry tore through salmon stocks that were much higher.

Strolling along, we saw an old cannery building now occupied partly by the Samish Nation and partly by a real estate office. The layers of meaning represented by the past, present, and future of that spot could probably fill a month’s worth of Taking Bearings.

Memorial

We finally reached that green spot on the map, Seafarer’s Memorial Park, where two works of art were as striking as the views.

One was the Seafarer’s Memorial itself. On two sides—with two more to grow—lists of names of those lost at sea offered a sober reminder to those leaving the marina through the gap in the nearby breakwater. The names of those from the Altair and Americus were included, too.

The other is Lady of the Sea, which represented those who waited and ran households and businesses in the absence of those out on the sea. A wife and mother, a child clinging to her leg, held a lantern high as a sign to returning boats and husbands and fathers.

The art and what they symbolized reminded me how dangerous many natural resource industries have been and remain. These activities—on the sea, in the mines, among the forests—are often destructive of the environment they depend on. But these symbols on the Anacortes waterfront prompt us to consider the precarious family situations such labor has demanded and continues to demand.

Return

I will return to Anacortes with an additional appreciation for this place’s history after this visit. It is the sort of appreciation that builds every time I slow down enough to consider what is in front of me now, and what might have been there before.

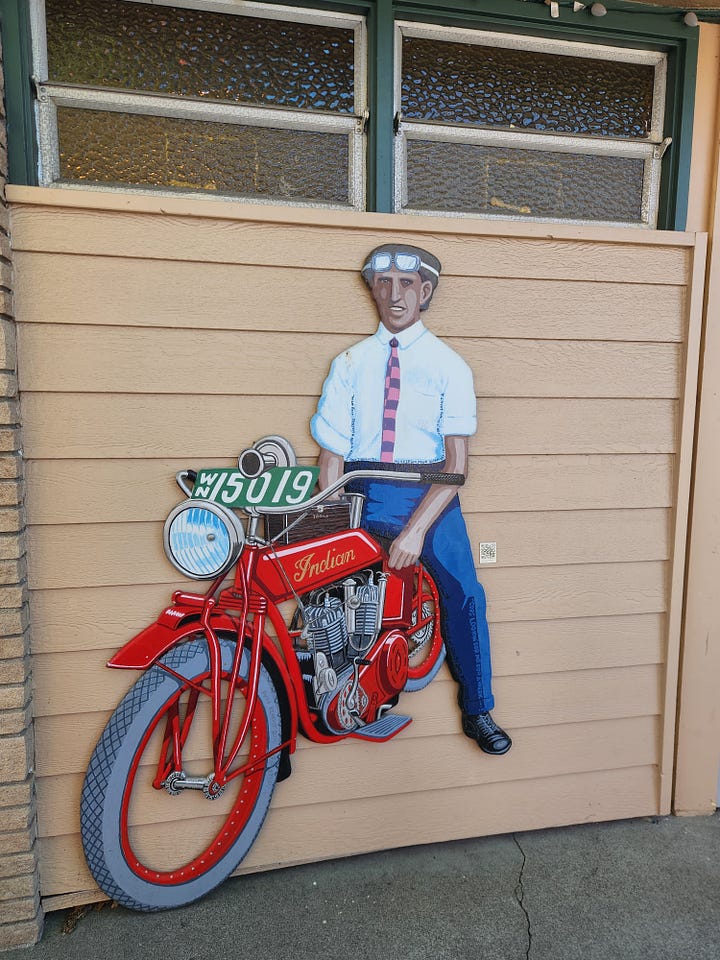

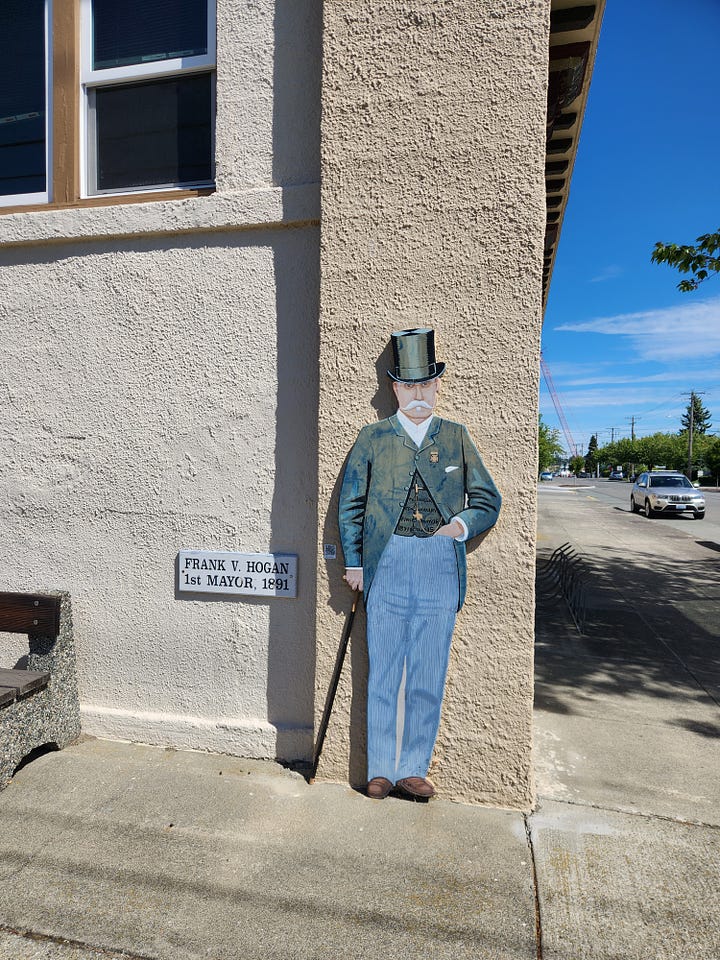

On the downtown buildings, life-sized figures are attached to buildings, likenesses of leading figures in the town’s history. And while you can find fancy homes for sale, there are buildings that need more than a little TLC. In them, perhaps, the ghosts of seafarers and their families mull over past days and ponder how things change and how they linger.

Closing Words

Relevant Reruns

If you look through my newsletter Archive, you can find several weeks where I focus on something water-related. This one might be the most closely related one to this week’s. I wrote an article once about smokejumpers, another occupation that can be dangerous. That essay is posted here.

New Writing

As I mentioned last week, I’ve been reporting on farmers markets. Here is the second story.

For paid subscribers, a new interview will post on Saturday that you won’t want to miss.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

I’m back to The Library next week. I’ll be continuing my series on Rural Hours, this time considering Summer. Stay tuned!