Summiting Mt. Baker, Revealing History

An 1869 Account from the First European to Climb Mt. Baker

Last week’s newsletter told of my visit to the Baker River watershed. This week’s focuses on an account of the first Europeans to ascend Mt. Baker. Typically, The Library week of my newsletter cycle investigates a book, but every once in a while, I choose something shorter (we all need breaks!). This week is one of those times.

In an 1869 Harper’s New Monthly Magazine story, Edmund T. Coleman (1824-921) published his account of ascending Mt. Baker. “Mountaineering on the Pacific” includes more historical tidbits than you might imagine for an adventuring genre. Read on!

Biography and Summary

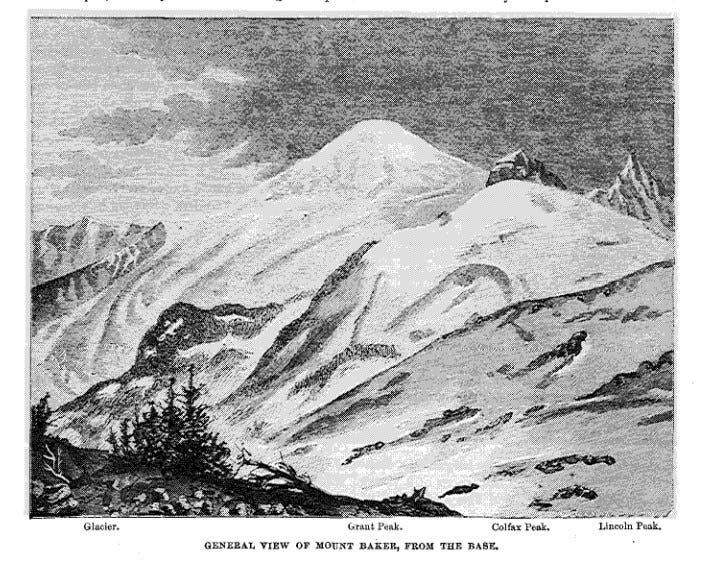

Coleman was an experienced English mountaineer, as well as a notable painter. A charter member of the Alpine Club, Coleman spent several seasons in the Alps, including ascents on Mont Blanc, before relocating in 1862 to Victoria, British Columbia. From this new location, Mt. Baker – “the silent sentinel of a solitary land” – beckoned to the seasoned alpinist. In 1866, Coleman first attempted to climb the volcano. Twice he was turned back: the first time by the Upper Skagit at the confluence of the Baker and Skagit Rivers (then S.báliuqʷ, now Concrete) and the second time by an ice cornice on a glacier now named for him. Coleman returned in 1868 and succeeded.2

“Mountaineering on the Pacific” tells of Coleman’s and his companions’ success at summiting Baker. The 25-page story traces what I imagine to be a fairly typical story in the mountain-climbing genre. (Admittedly, I don’t read this literature often.) Coleman described preparing for the journey, including the brief accounts of his earlier attempts and getting outfitted and connecting with regional personalities. He included details of the journey up the Nooksack River with his Nooksack guides, Squock and Talum, and then the mid-August ascent up the mountain. There are hardships (e.g., low on food, avalanches, ice) and moments of adventure (e.g., reaching the summit, shooting the rapids downstream). But compared with some mountain literature, this seems a mild account.

The Good Stuff

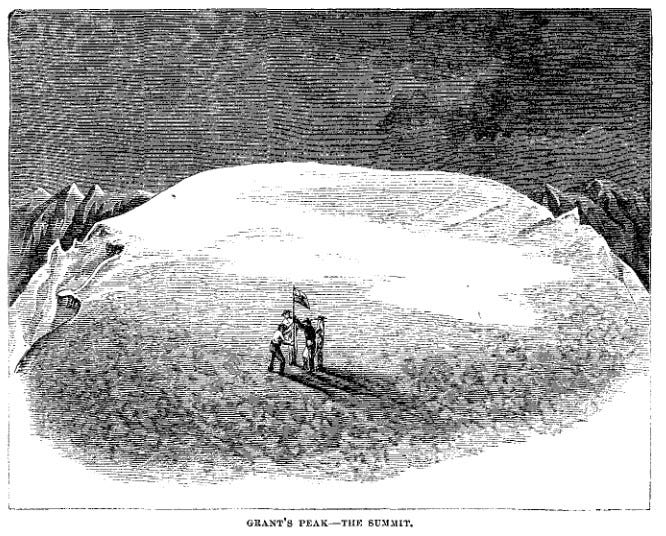

But don’t mistake mildness for uninteresting or unimportant. Especially for someone attuned to Northwest history, “Mountaineering on the Pacific” is packed with fascinating details. In fact, the ascent part of the article offers the least interesting part (to me). The part of the mountain-climbing that most piqued my curiosity was how they named so many peaks and other landscape features after Union and Republican heroes of the 1860s – Lincoln, Grant, Sherman, Colfax.

The Economy

What intrigued me most were the details of society developing in north Puget Sound. In the first few pages, evidence of class stratification appeared. Local members of Coast Salish tribes provided labor, especially for transportation. A Chinese cook was mentioned, too. The economy, predictably, divided along racial lines.

The emerging extractive economy also was evident in these pages. Coleman describes coal mines in what is now Bellingham and the roots of a timber economy that promised a prosperous future. (He even notes a telegraph.) Coleman pitches Bellingham Bay as the terminus for the Northern Pacific Railroad, which would transform the area after the downturn it was currently suffering. His future vision:

the winter of its discontent may soon become glorious summer, and Whatcom, now deserted and forlorn, arise like a phoenix from its ashes.

The Society

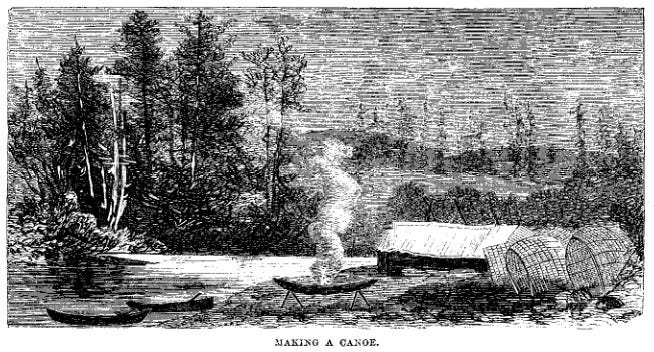

Coleman uses the language of “savagery” in his descriptions and writes with biased relief that the Lummi “have already abandoned their ancient barbarous habits, and have adopted those of civilization, temperance, and religion.” These and similar comments and sentiments are as unsurprising as they are ethnocentric. But his descriptions observe as often as judge, so some useful information can be gleaned, such as how the Nooksack prepared elk or about the mansion of Umptlalum (a Nooksack leader), or how Indigenous people in the San Juan Islands set up nets to catch waterfowl or how canoes were prepared for travel:

The bottom of the canoe is spread with small branches and twigs, and then covered with matting of native manufacture. One’s blankets are placed against the thwarts and form a soft cushion, against which he can recline and be as comfortable as in a first-class railway carriage. When camping on shore at night the mats are spread out on the beach, and with one’s blankets make a soft bed.

(This passage also shows the class elements in traveling.)

One sentiment I’m not sure I’d seen expressed before was Coleman comparing Indigenous peoples’ lives to the pastoral ideal of ancient times, but that’s here, too:

The loveliness of the scenery around, the comfort and ease with which they gain a subsistence, the gentleness and dignity of their manner, nurtured amidst the freedom of their native haunts, all combine to remind one of that pastoral life of the olden time which painters have delighted to illustrate and poets to sing.

The Place

But beyond the people Coleman encountered, what comes across most is Coleman’s infatuation with the Northwest landscape, which is “surpassingly beautiful.” And that beautiful place meant a prosperous future was set:

Indeed, the scenery around has many and varied elements of the beautiful. When standing here at early morn, looking out upon the tranquil scene, in the distance the Olympian Mountains bathed in mist, and nearer the grand outline of Orcas Island looming up like some great fortification, imagination pictures the future, not perhaps far-distant, when these silent shores shall be lined with wharves and resonant with the throng of busy multitudes.

To be sure, nature was not always benign, for that would not make for a dramatic story. So, Coleman, at key moments, emphasized something more powerful:

We have to deal with nature in her sternest aspects – torn and convulsed, at war with herself – bearing on her face the scars of countless ages of desolating power, of the flood of the avalanche, and of the burning tempest.

Such descriptions, infused with the Darwinian debate convulsing the scientific world, could then be contrasted with breathless reverence:

We were in a temple not made with hands. There was no need of Sabbath bell to sound the call to worship. The sublimity of the scene lifted us above all worldly considerations, all thoughts of self, and evoked involuntary exclamations of praise.

This language showed the transformation of mountains that had rocked English culture a century or two before Coleman wrote. Clearly, Coleman had inherited the Romantic shift described in the classic study by Marjorie Hope Nicolson, Mountain Gloom, Mountain Glory, that showed the revolution from mountains being a place of gloom and wrath to a place of glory and sublimity.3

The Climber

Beyond broad cultural changes that Coleman exemplified were personal changes, too.

I had left Victoria jaded and depressed, sick of the monotonous round of my ordinary occupation, harassed by the multiplicity of petty details and preparatory arrangements connected with this expedition. The continued responsibility of it had strained me to the utmost, but now, when success had crowned my efforts, bodily fatigue vanished, and the mental weariness, that sense of oppression which is worse than any bodily fatigue, was removed, and I was lifted up with a feeling of renewed life. My mind was open to all the genial influences of the season and the hour.

This, then, was the reward. Although the article described planting flags and drinking toasts during the descent – a concoction they called the Mount Baker Cocktail (later to be served in Victoria bars) – the true climax was personal renewal.

Final Words

I have not written about mountain climbing before; however, I have written about another 19th-century man who spent time in remote mountains and have investigated exploration. (These are, I admit, stretches for relevance!)

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

Next week is The Wild Card, and it concludes my 13th newsletter cycle. That’s one year of this newsletter! I’ll be using the opportunity to look back and ahead. Stay tuned!

I’ve seen sources lists his birth date in 1821, 1822, 1823, and 1824.

A handy summary is Fred Beckey, Range of Glaciers: The Exploration and Survey of the Northern Cascade Range (Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 2003), 291-98

Marjorie Hope Nicolson, Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory: The Development of the Aesthetics of the Infinite (1963; reprint, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997).

Adam, Coleman was an interesting chap. He was one of the earliest people in the US to use the term glacier in reference to an active glacier in the lower 48; he proposed harvesting the glacier in order to sell the ice to San Francisco; and he mentioned creepers, or what we now call crampons. DBW