Next week, I’m heading to Minnesota where I’m delivering a lecture about my last book, Making America’s Public Lands. So in between everything else I’m doing, I’m thinking about public lands. In particular, I’m thinking about both of those words—Public and Lands—and what happens historically when the are in the same vicinity.

For this week’s trip to The Classroom I am sharing one part of the story from the book that explores a key moment in the history of public lands—both the public nature of the lands and what had happened to them. Read on!

The Ragged End

In 1926, a district ranger named Fred W. Croxen who worked on the Tonto National Forest delivered an address at a grazing conference in Phoenix. Although the ranges of Arizona had been abundant in the 1880s, Croxen explained, now they were “at the ragged end of it all.”

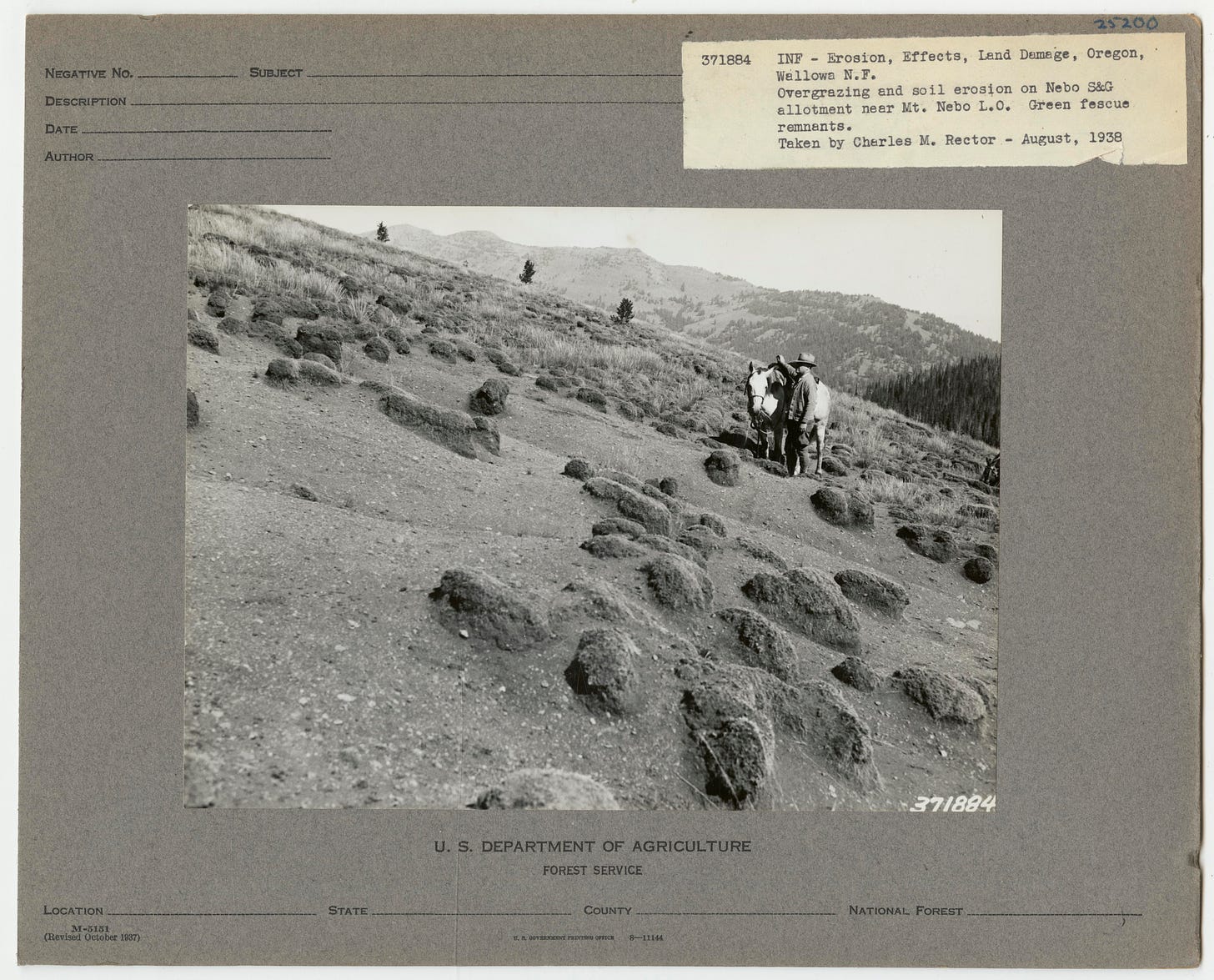

Croxen did not make this assessment in a vacuum, and it didn’t apply only to Arizona. The West’s rangelands by the interwar period had been pummeled by sheep and cattle. The Forest Service had begun incremental regulation of grazing on the lands it managed. And it sponsored experimental research to improve scientific understanding so it could apply better practices.

But conditions were bad, and governments took note.

Who Wants These Lands?

In 1929, President Herbert Hoover created a Committee on the Conservation and Administration of the Public Domain. It served until 1931 and functioned as the third public lands commission. These commissions periodically popped up in public lands history. They survey and assess the lands and laws governing them and issue conclusions that often, though not always, formed the basis of new legislation.

The previous commission, appointed by conservationist president Theodore Roosevelt, asserted that orderly development of the western range could only happen under national control. Hoover’s predilections and governing philosophy were more conservative than Roosevelt’s. Not surprisingly, Hoover’s commission concluded that “private ownership . . . should be the objective” for these grazing lands.

The commission proposed granting the remaining public domain—those lands not already claimed by individuals or corporations or not in a national forest, monument, or park—to the states. This was no meager amount of land; it was about 235 million acres, nearly the size of Egypt. In the plan, though, the federal government would retain subsurface mineral rights.

States balked.

That would be like giving the states “an orange with the juice sucked out of it,” said Senator William Borah, a Republican from Idaho. The land’s value as grazing land, Borah was saying, had been sucked dry, depleted beyond value.

Utah governor George Dern complained that western states already controlled millions of acres like this that yielded no income. “Why should they want more of this precious heritage of desert?” he asked. Instead, Dern wanted federal range rehabilitation, explaining, “our ranges are being very seriously depleted and deteriorated, and they have got to be built up, and built up right away, or else they will be beyond repair.”1

The proposal was dead on arrival.

A couple points of emphasis. Like a periodic pandemic, this idea appears—that federal lands should be transferred to states. Here was a historical instance when there was an outbreak of this notion. When states looked at the prognosis, they said, “No Thank You.” Also, the disposition of these lands were a public matter because the nation’s citizens owned them. Last, they were beat up. The primary reason Borah and Dern didn’t think states should take them is because their value had declined because largely unregulated ranching across the West diminished the ranges’ capacity to feed animals, hold water, or maintain soil quality.

Another assessment

When the Hoover administration was resoundingly voted out of office, the Franklin Roosevelt administration investigated these lands again. Rather than a broad public lands commission, the Forest Service took the lead. Its report, The Western Range (1936), documented the conditions of grazing lands, including those managed by the Forest Service and those that remained part of the public domain and were mostly unmanaged.

The portrait was not pretty.

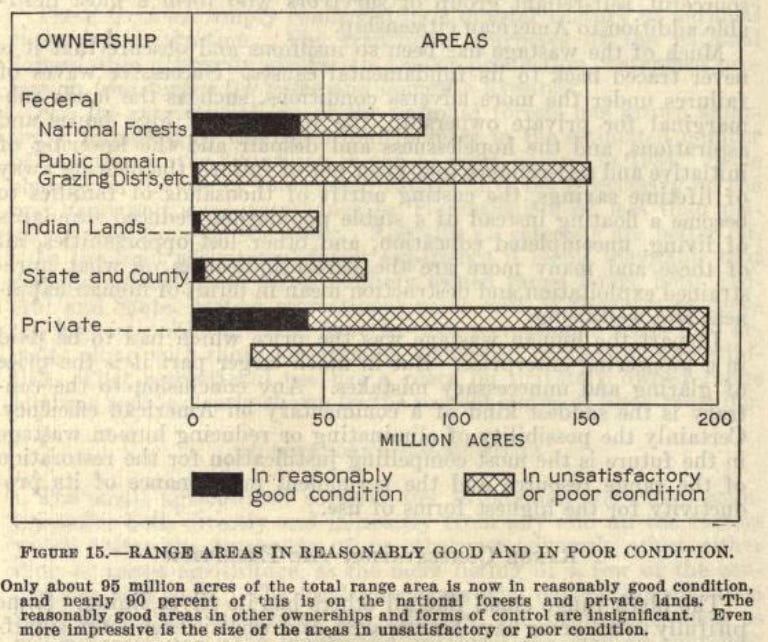

The forage on the western range had been depleted by half. The public domain was the worst: declining by two-thirds. The Forest Service was only down one-third. To be sure, a Forest Service report might be cherry-picking examples to show its enlightened management. And of course, The Western Range was a political document, part of the agency’s efforts to push back against a plan by Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes who wanted his department to take over Forest Service rangeland. But no serious observer at the time looked at the range—98% of which “eroding more or less seriously” according to the report—and concluded the range was functioning well ecologically or economically.

And that made range conditions a public question—that is, a political one. (Subsequent reform efforts might be a topic for another newsletter.)

Significance

As long as I have written about public lands, I’ve said that they most appeal to me because of their public nature. That is, we all have a stake in them—in their conditions, in their management, in the process by which such things are assessed—through their administration by government bodies. I’m not naive enough to believe that a government agency will always be best. And I am historically literate enough to know that government commissions and reports will not produce objective results without agendas. Governments are constituted by people, after all, and I’ve met enough people to know that objectivity isn’t their strong suit.

But throughout public lands history, I become most intrigued at moments like this. A crisis seemingly exists, prompted by an ecological decline too obvious to ignore, and the public responds. In that response, ideas and data are put forth. Occasionally, a grand public debate ensues. Sometimes, reform happens and that produces improvements.

From the “ragged end of it all,” the government could not look away. The public interest demanded attention, and because these lands were public, the attention remained open to public scrutiny.

Closing Words

Relevant Reruns

Because so much of my writing has focused on public lands, I could link dozens of pieces here. I’ll spare you that. But this earlier newsletter traces some evolution in thinking about the public domain that is important to this history. And this article focuses on public land commissions.

New Writing

A couple stories of mine have appeared about local agriculture in the last week or so. One looks at reduced tillage methods and another profiles a local tulip farmer and his garden. I hope you’ll read them. More stories are in the works, too.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

Next week is The Field Trip, and I am scratching my head to figure out how I’ll have the time to get out. Stay tuned!

You can find this recounted in my book, and I relied on James R. Skillen, The Nation’s Largest Landlord: The Bureau of Land Management in the American West (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009), 5-7.

Thanks for this perspective. I worked in range management for the Forest Service back in the early 2000s. It was pretty bad then, the condition of the range. I still keep tabs on the ongoing range dilemma, mostly through Western Watersheds Project. It can all be very depressing, but it is a bit cheering to see how bad it was once, when it was completely unregulated. I'd say we've come a long way, with a long way yet to go, of course.