This week’s newsletter circles back to The Classroom, and it begins a series of three (at least) connected issues that will link the next couple weeks. I’ll be moving beyond the Pacific Northwest for these next few, getting me back in touch with earlier (and still on-going) projects.

As an environmental writer, I am drawn often to questions that dance around property. One reason is because the “environment” does not conform well to legal concepts of property. Keep your eye on parts of nature long enough and you are sure to see a property line appear or disappear or twist all around. That’s certainly the case with the history lesson here. Read on!

Elk History

The history of wildlife in North America after European colonization is fairly depressing, as species after species faced declining numbers and shrinking habitat. Elk, also known as wapiti, represent a specific case study to this generalization.

Increasing human populations shrank elk habitat and market hunters and poachers threatened the herds. By the turn of the 20th century, the Rocky Mountain West centered on what is often called the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem remained wapiti’s best hope. At the time, wildlife officials understood hunting as the main harm to wildlife, not recognizing the roles habitat served. Yellowstone National Park functioned as a game reserve and prohibited hunting. Officials tracked down poachers, and, outside the park, they regulated legal hunts.1

But for the herd south of Yellowstone park faced deeper problems than illegal hunting. In effect, property threatened them.

Stuck in Jackson Hole

In centuries past, elk moved south toward the so-called Red Desert of southwestern Wyoming, passing through Jackson Hole on their way. When ranchers and farmers moved into this place, they disrupted age-old land-use patterns, most visibly with fences (and communities). In a relatively short time, these new presences on the land made elk unable to continue to the warmer steppe where winter forage was available. So, the elk piled up in Jackson Hole, a high valley surrounded by mountains, where they tried to manage through the winter. This congregation became a spectacular disaster.

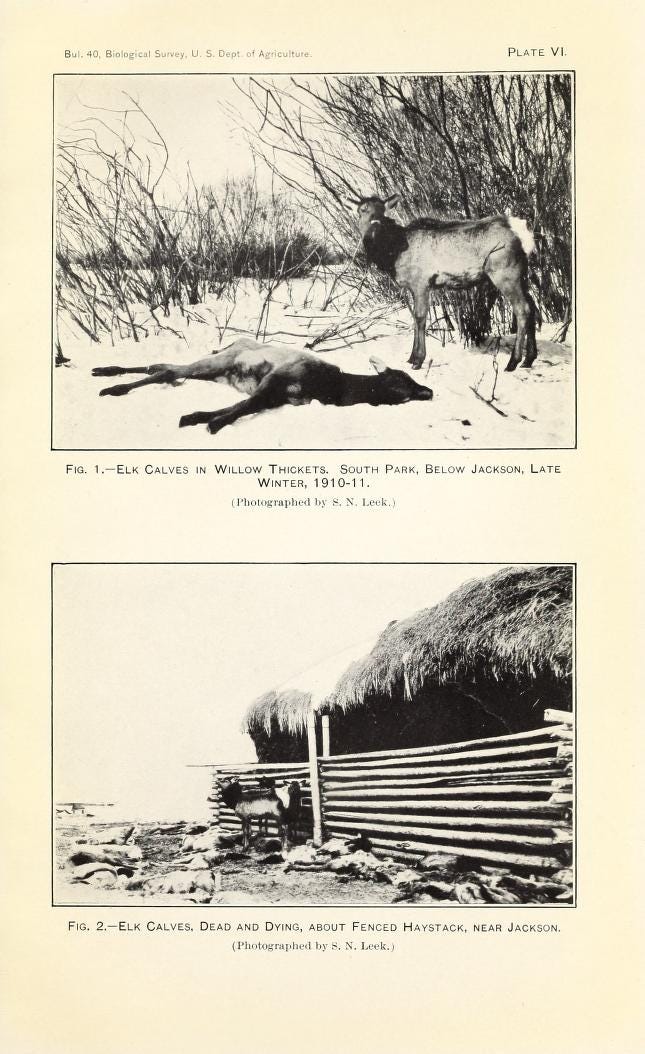

The herd of 20,000 to 30,000 animals ate more forage than the valley could provide, especially after domestic cattle ranching made inroads. Then, an especially cold winter in 1910-11 killed 5,000, and many that did not die were weakened. The appearance of starving elk pulled on public heartstrings.

Stephen Leek, the so-called Father of the Elk, raised the profile of the issue by lecturing all over country.2 Contemporary newspaper articles reported Leek’s effectiveness from places as far away as Pittsburgh. Leek’s photographs offered stark testimony to the dire conditions, but he also told stories of the situation. Leek reported bull elk pressing noses against his windows, like proverbial poor children peeking in at the rich. Leek shared that a handful of ranchers fed emaciated elk out of their own haystacks. “Often on the coldest nights,” Leek explained, ranchers “have to go out and sleep in their haystacks. The elk are so crazed by hunger that they will go through any sort of fence.” Such a circumstance could not last.3

Government Help

In 1905, Wyoming created a game preserve south of Yellowstone, on the northern edge of Jackson Hole, for elk winter range. Insufficient. In that terrible 1910-11 winter, Wyoming appropriated $5,000 to supplement elk feeding. The next year they turned to the federal government, asking for more money.

The US Bureau of the Biological Survey (a forerunner to the US Fish and Wildlife Service) investigated the conditions, and the published report (which included some of Leek’s photos for effect) framed a new approach. The author, Edward Preble, built a case for a new conservation measure. A few years before, Wyoming had asked for federal help in acquiring ideal land for a wildlife refuge. Local ranchers opposed it. But a couple rough winters with elk nibbling at ranchers’ hay and dying in great numbers built support.

The federal government provided $20,000 to purchase hay. In addition, it purchased 1,760 acres and withdrew another thousand acres from the public domain to create the National Elk Refuge just north and east of the town of Jackson. The Izaak Walton League donated more land to expand the refuge. At the refuge, officials fed elk to prevent starvation, an action meant to be temporary that has become a nearly-permanent measure, which has produced some problems (perhaps to be explored in another newsletter).4

Layers

Layers upon layers are revealed in this short history. Landowners changed patterns on the landscape. That caused elk to alter their habits. Wildlife are considered state property (except, typically, in national parks). State and national governments weighed in to help support elk. So did a conservation organization that acquired private property only to make it public land. Within the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, elk move between federal parks and forests and refuges, as well as state lands and private lands.5

These circumstances require cooperation for managment and patience among constituencies. But elk (and other wildlife) make questions of property rise to attention. I’ve found that once I begin trying to untangle nature and property, the more I question the appropriateness of such categories.

Final Words

I wrote an article once that featured conservation in Jackson Hole, although it focused on a different episode; you can find it here. I’ve also written about elk in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, focusing on the 1960s and how the National Park Service addressed an abundance of elk.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

Next week, the Field Trip returns and I’ll be reporting on a trip (several years ago) from the Grand Tetons. Stay tuned!

ATTN. New Notes Feature

Notes is a new space on Substack where we can share links, short posts, quotes, photos, and more. I plan to give it a try to interact with subscribers and network with those who share similar ideas or appreciate good writing. I hope it becomes a positive place where interactions are easy and common.

If you are interested, head to substack.com/notes or find the “Notes” tab in the Substack app. As a subscriber to Taking Bearings, you’ll automatically see my notes. Feel free to like, reply, or share them around!

As we move in the direction of summer, I’m making a push to increase my subscribers and the engagement with these Taking Bearings newsletters. So if you want to help with that, please press the Like button below or leave a Comment. If you know others who might enjoy this weekly newsletter, please share it with them. And if you are able, consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Thank you for reading.

Karl Jacoby, Crimes Against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001) tells the history of poaching and Yellowstone.

Earlier, Leek participated in a posse that killed two Bannocks in 1895, part of the ubiquitous violence associated with colonizing the US West.

Press accounts are available in the Stephen Leek Papers at the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie.

Robert W. Righter, Crucible for Conservation: The Struggle for Grand Teton National Park (1982, reprint; Moose, WY: Grand Teton Natural History Association, 2000).

Since Grand Teton National Park was created, many private lands were absorbed into the park.

Colleen Friday, an Arapaho artist, made several evocative pieces addressing Leek’s actions.