Before I start this week’s newsletter, please allow me to make an appeal and an offer.

August will mark two years of Taking Bearings, two years of weekly thoughts and lessons about place, history, and writing. I am hoping to increase subscribers and would be grateful if you shared this newsletter with a friend or family member you think would enjoy it. I’ve turned on a referral program. After four referrals, you will be comped free access to paid content for a month (and the rewards increase with more referrals).

I’m also asking that current free subscribers consider upgrading to the paid option. To celebrate the pending two-year anniversary, throughout July I am offering a discounted subscription rate.

Thank you for your consideration. ~Adam

Western Washington edged into the 90s this week, a rare occurrence in the past. This month’s interview for paid subscribers focuses on a writer who explores the desert Southwest. Combined, these have put me in mind of deserts and a brief trip I took to Capitol Reef National Park almost five years ago. For The Field Trip this week, I’m doing a retrospective report. Read on!

Lingering

Capitol Reef National Park is not as famous as some of Utah’s other national parks like Arches and Zion. That made it so I could find an open campsite in August 2019 on a research trip I took for a project I have not yet completed—and may not ever.

I rolled into the Fruita Campground toward the end of a big swing through the West that took me from Washington to Idaho to Utah to Nevada to Arizona back to Utah and Nevada and Idaho and Washington. After a warm night at the campground amid remnant orchards (Fruita remember), I took an early morning hike along the Cohab Canyon Trail that refreshed me after the very long day of driving the day before (something I wrote about before here).

Not content and not needing to get on the road early, I headed out for another short hike at the Capitol Gorge Trail. That required driving to the end of the blacktop and heading along a dirt road that sometimes closes when flash flooding is a risk. I bounced along for a while before hitting the trailhead.

Writing on the Wall

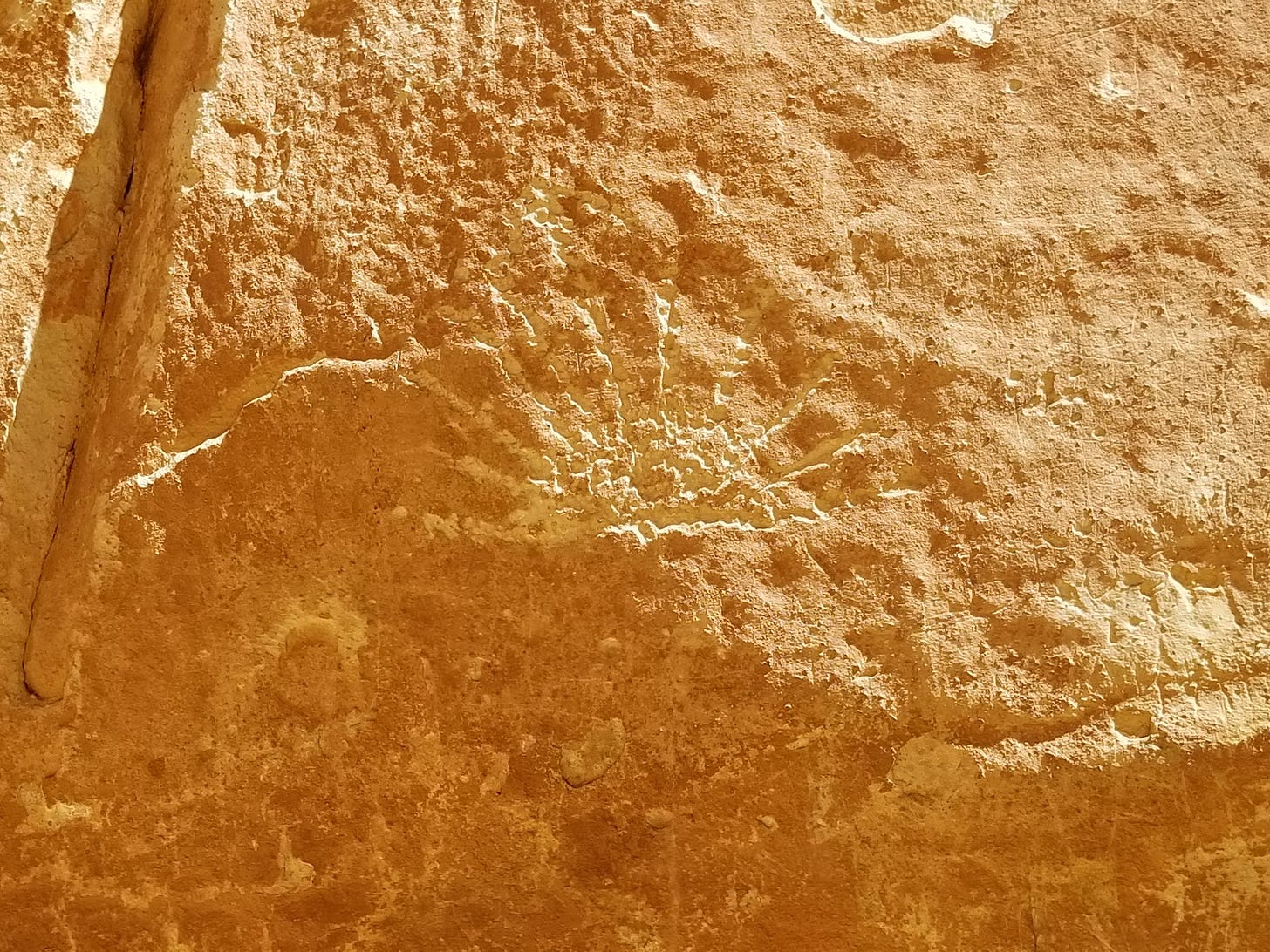

Almost immediately, the trail slips between cliffs—a relief, because they cause the only shade on a hot August day. It didn’t take long to find the first human traces on the rock walls: a sun etched into stone.

At this point on my trip, I had seen plenty of human marks on the land. (Betatakin Cliff Dwelling at Navajo National Monument and Walnut Canyon National Monument were favorite large-scale signs of earlier chapters of ongoing stories of navigating the desert.) But this sun is not why people walk along the trail. The Pioneer Registry is.

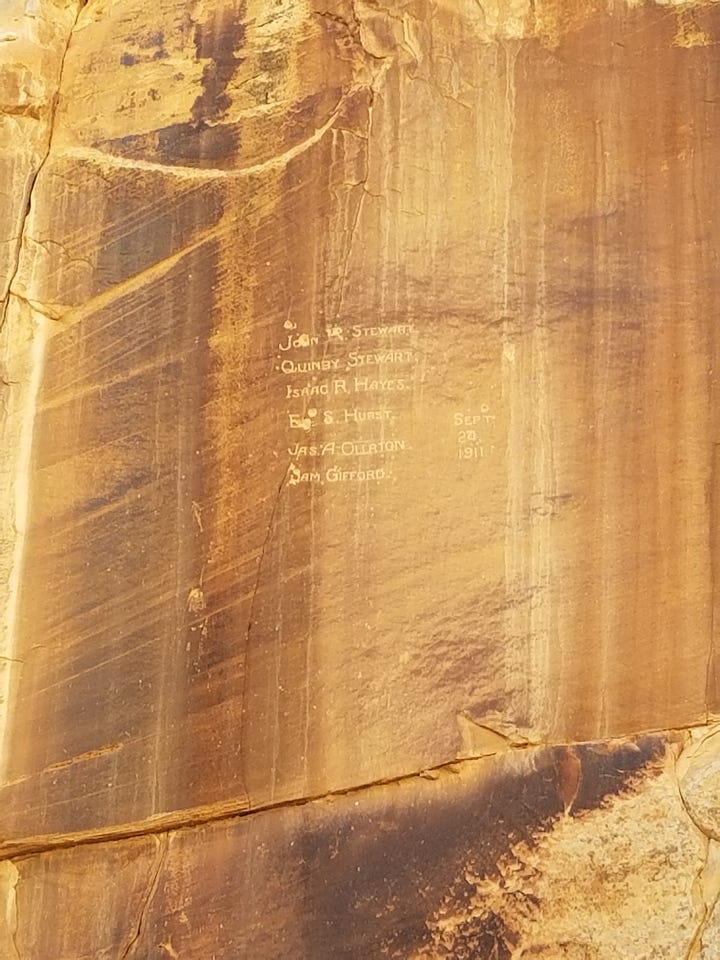

Along vertical walls dozens of people left their names and dates. The first ones I noticed were high up. Six men left their names from September 1911, a carving feat that would have not been simple given the height above the desert floor. I imagined what it must have taken and decided they hung off the top somehow, vaguely conjuring the image of window washers and skyscrapers.

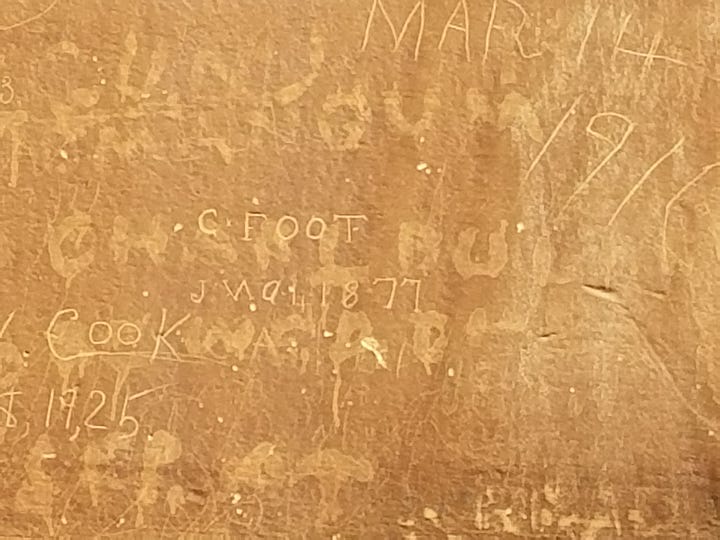

As I kept walking through this quiet passageway, I searched for older dates. The oldest record I saw was 1877—a momentous year in American history when the federal government abandoned Reconstruction and freedpeople in the former Confederacy.

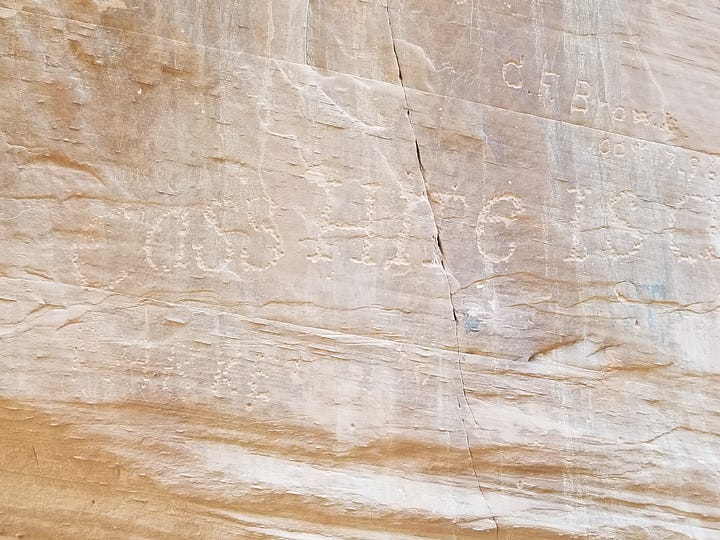

I did not expect to see familiar names, but Cass Hite stood out. The day before I passed a submerged town, Hite, where I crossed the Colorado River, also submerged beneath Lake Powell. Hite lived a life worth writing about and knew the fame/notoriety of killing a man and being pardoned by the governor. And here was his name.

Against these pale walls, I noticed cursive and printing, even with serif-type “fonts.”

Passing through, people left their marks. Wallace Stegner characterized this part of Utah in his 1942 book, Mormon Country. Stegner thought the place was isolated enough that people there “preserved the habits and psychology of the little Mormon towns well after they had been diluted elsewhere.” That means, perhaps, the people who lived there when he wrote his book shared attributes of those who etched their names on the wall. As he noted, “In country like that, habits linger.”1

So do marks on the wall.

Water and Rocks

I pressed onward from the Pioneer Registry to The Tanks. Not a monumental spot, but these pools in the desert remind us of the value of scarcity.

The real power of water, however, impressed me elsewhere. While heading back to the trailhead, I noticed pockets in the walls. These holes revealed some sort of weakness in the stone, I suppose, eroded after countless storms.

Inside these pockets, around eye level and higher, were rocks. Clearly flash floods had raised the rocks high enough to deposit them here. I had seen the warnings and noticed the open gate that could close the road down. But these rocks at the height of my head offered far stronger signs of what a flash flood might do.

And I might add, far more impressive than a name on a wall.

Closing Words

Relevant Reruns

Reading this old newsletter sets up this week’s quite well. This story takes a different angle on the human history within parks.

New Writing

A new reported story about local government getting feedback from the public appeared this week.

On Monday, a new interview will post. This feature is only for paid subscribers, so if you want access—and it’s a good one—consider upgrading your subscription.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

I return to The Library next week. Given my recent focus on national parks, I may try to find something suitable to stay on theme. Stay tuned!

Wallace Stenger, Mormon Country (1942; Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970), 156, 157.