Sometimes, The Field Trip takes me to new places I want to learn about. This week, though, I took a very short trip to a place that has become quite familiar to me in the last year of living here. I went with a different purpose this time and returned with a longer, stronger sense of its history. Read on!

To the Trailhead

Spring has arrived with all its seasonal signs. Longer days. Sun more frequent. Frost less frequent. Songbirds chirping. Migratory birds leaving for places further north. Cycles are not only seasonal; they stretch into recognizable patterns over decades as well.

On our first warm, sunny weekend day, I took a short drive. The route wound through lowland drainages with foothills covered in conifers. Orange signs announcing “Trucks Turning Ahead” signaled logging roads into private timberlands where harvesting happens back from the road.

The only small community along the way surrounds most of a midsized lake. It is heavily timbered but the homes, many of them second homes, scatter throughout the trees. Once, a sawmill worked the forest here and supported a community with stores and taverns and such. Now, there is no place to spend money.

Once the highway’s speed limit resumes at 50 mph, an area just west of the road opens up. A creek runs through the bottomland that is flat and open for not even 1000 feet. It’s small, but noticeable, in this mostly-timbered area. At the head of the long, skinny clearing is my destination: the Nakashima Heritage Barn Trailhead.

Western Washington History’s Cycle Exemplified

Now, this spot is managed by the Snohomish County Parks and Recreation department, but its history exemplifies the cycles of history present throughout much of western Washington.

The thick timber growth that crowds the foothills represents a fraction of the forested wealth that blanketed western Washington two centuries ago. Loggers first used water to transport logs, but railroads expanded access to far more timber. Between 1889 or 1890 (sources differ), the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railroad pushed through this lowland gap.1

With that secure transportation connection, more remote trees and their products could get to market, and more people moved into the forests. Here, along the small creek, the Bass Lumber Company built a shingle mill. As in many parts of western Washington, this place soon transitioned from forest to farm. This transformation was an article of faith, an obvious and undisputed sign of progress to Americans for generations.2 Flat ground tended to remain farms, but foothills were allowed to return to trees.

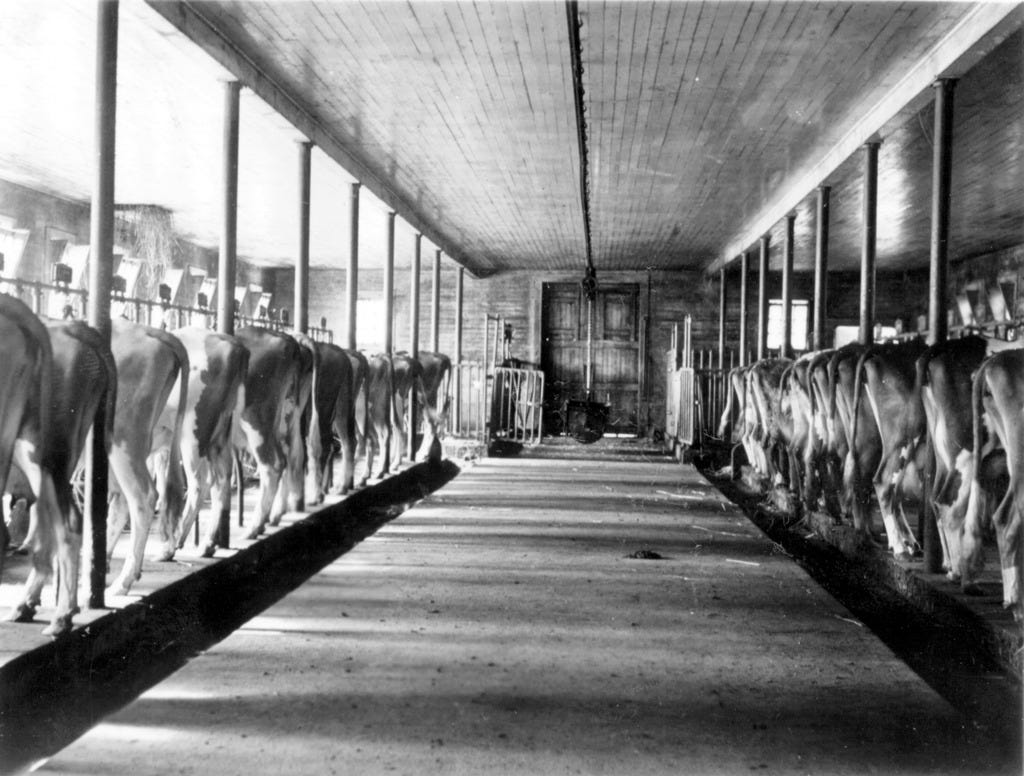

In 1908, Bass got married and built the barn. The onetime forest and mill became a dairy farm. Although Bass had long since moved to Seattle, in 1937, the dairy farm with purebred Guernsey cattle sold.

The Brief, but Defining, Nakashima Years

The Nakashima family purchased this farm. The title was registered in Takeo’s name, the American-born son of Kamezo and Miye Nakashima. Discriminatory laws prohibited Japanese immigrants from owning land, only one of the obstacles placed in front of them.

Kamezo immigrated in 1907 and worked first in shingle mills and then on farms in Snohomish County, part of the emerging logging and agricultural economies there. The Japanese population in Snohomish County was tiny compared to its southern neighbor, King County, with Seattle as a central hub for immigrant communities.

Kamezo built a family while building skills in these rural economies. The Nakashima’s farm grew to 1200 acres and 90 head of cattle.3 Although they grew crops to feed their animals, the dairy operation was their money-maker. They sold some of their milk to Darigold, long a Northwest mainstay.

The American dream of immigrants making good and building a place for their families took a forced diversion, though. President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the incarceration of Japanese and Japanese Americans on the West Coast in early 1942, a couple months into the US involvement in World War II.

In April, Takeo sold the farm for $10 per acre, a figure well below market value.4 A story says the buyer arrived to buy a bull only to be told he would need to buy the entire farm to get the animal. Takeo then was forced to Minidoka in southern Idaho, while his parents ended up at Tule Lake in California for the remainder of the war. Some of the family were visiting Japan when the war broke out and remained there.

The Nakashima family owned the farm for less than five years. However, today the park focuses on this legacy to the exclusion of any other part of the land’s history. This emphasis would have been unthinkable when I was born; that the injustice is highlighted represents something about how historical awareness has changed.

After their imprisonment, the Nakashimas relocated to Seattle working in an urban economy instead of in rural Snohomish County.

The Final Transformation…For Now

The farm changed hands a few more times until the Trust for Public Land acquired part of it in 1997. The county took it over. The railroad was abandoned a decade or two before, and it has been transformed into a paved trail, frequented by walkers, bikers, and runners. This rails-to-trails change has arrived at many places, in part because of urban recreation has risen in importance. The recreationists trace what was once a vein of industry.

I am one of those who runs this trail regularly. Because I am a historian, the barn and the stories it contains and represents always occupy my mind when I visit. This is my normal mode; I move through the world thinking about past stories. When I visit the Nakashima Heritage Barn Trailhead, I typically think of the injustice carried out. Forced removal has been a too-frequent strategy to take land in this nation.

On this recent trip, though, I widened my vision a bit. That injustice that took 120,000 people – the majority of them American citizens – from their homes and imprisoned them remained prominent. But I thought in a longer time frame. Hacking a farm from that forest, laying down tracks from small hamlets to tiny towns. Second- and third-growth timber harvest continues, as you can see on the ridge above. The recreational path where commerce once drove represents another temporary endpoint. From thick forest to lycra-clad cyclists, this is the trajectory of Northwest history, a cycle whose next turn we cannot always anticipate clearly.

Closing Words

I have not written about these topics so directly before. However, I once wrote a short article about the transformation of forests to farms, using a series of photographs to illustrate. The online journal it appeared in, Idaho Yesterdays, is not fully available now, but I have posted a .pdf that allows you to read it.

This week 99% Invisible, an innovative and interesting podcast, posted its latest episode called “The Wilderness Tool.” The episode uses the crosscut saw to explore wilderness. I was interviewed twice for it and my comments are scattered throughout the episode. But you should listen to it for its creative exploration of the topic; it’s worth it.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

We return to The Library next week. If all goes well, I’ll cross the continent (figuratively) and report on a classic conservation book that centers Florida, well beyond my comfort zone. Stay tuned!

If you enjoyed this newsletter, press the Like button below or leave a Comment. If you know others who might enjoy this weekly newsletter, please share it with them. And if you are able, consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Thank you for reading.

Not long after this, the Northern Pacific absorbed this local line.

A short summary of this process is Steven Stoll, “Farm against Forest,” in American Wilderness: A New History, ed. Michael Lewis (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 55-72.

Reportedly, the dairy there is the only one in the county ever owned by anyone of Asian or Pacific Islander descent.

Many families lost everything, unable to sell in time.

Adam, Thanks for your story. I also travel that trail regularly and thought you might like to read what I wrote.

https://streetsmartnaturalist.substack.com/p/the-joys-of-repeat-travel

David

Request to please not use the timber industry euphemism “harvest,” and replace it with what it is, “logging.” The H-word implies trees are nothing more than a crop, like wheat or barley. Fact is, even frequently logged forests are much more than that. Thanks.