Finding Grant McConnell and the North Cascades

Loving a place and becoming an applied political scientist

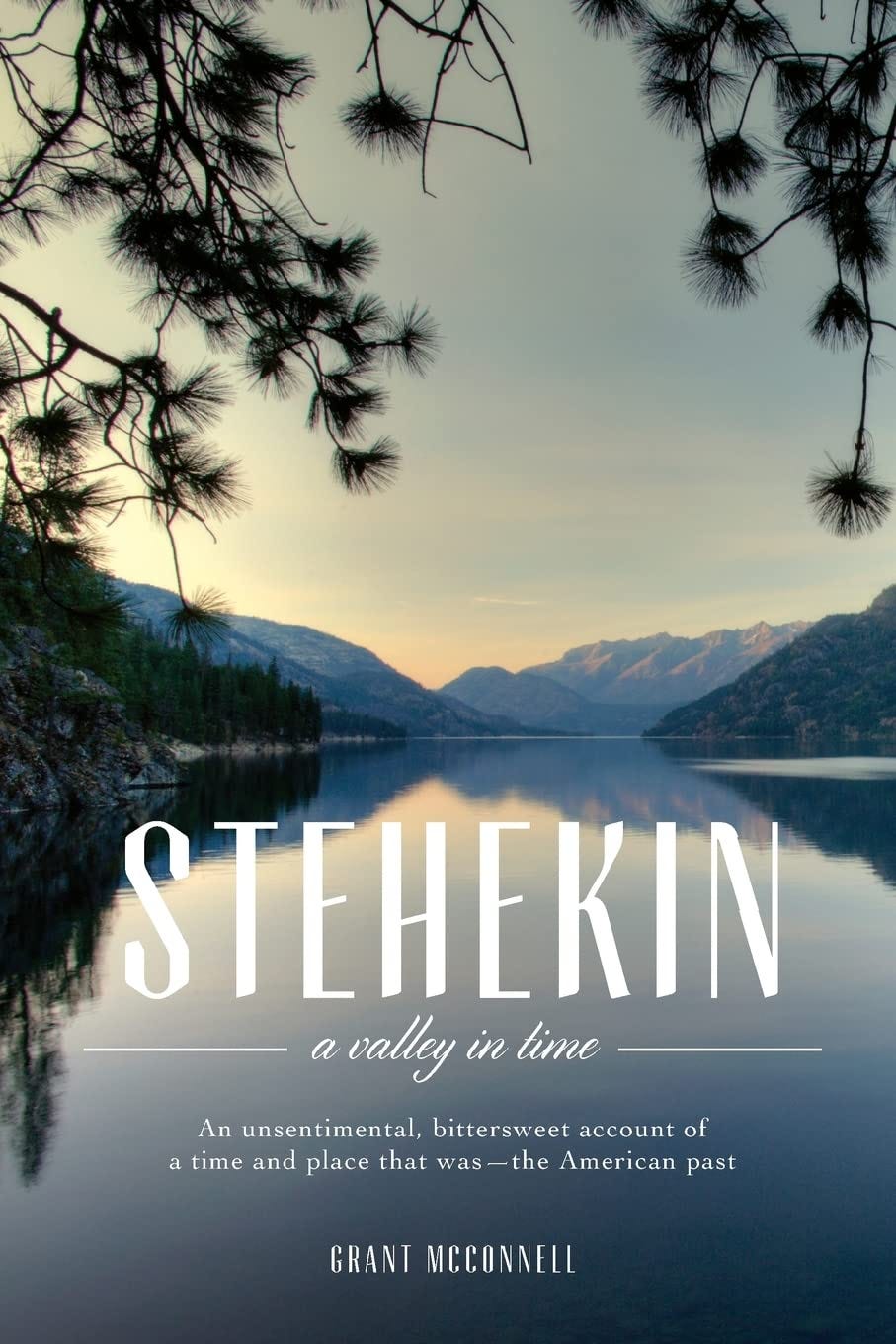

The story of Grant McConnell (1915-1993) is one of convergences. It also is the story of someone who fell in love with a place, a type of affection whose depth transformed his academic career and catalyzed activism on behalf of a spectacular landscape: the North Cascades.

Finding Stehekin

When McConnell first went up Lake Chelan, he recalled in an oral history, “I found what I’d been looking for.”

That was in 1937, and it took him three years to return with his wife, Jane. Then as global war loomed, Grant worked first with the Farm Security Administration and then the Office of Price Administration. Finally, he joined the Navy where he patrolled the Pacific coast and then went off to the East China Sea. Meanwhile, Jane worked with the U.S. Public Health Service.

During those years, by letters, Grant and Jane dreamed of a postwar future where they lived in the mountains. After considering several choices, they landed at Stehekin.

On May 2, 1945, Grant’s destroyer sank off Okinawa, just three months before the war ended. On the very same day, nearly 6,000 miles away, Jane arrived in Stehekin, a small, isolated community on Lake Chelan where she had purchased some property.

After the war, they lived simply—on $35 dollars a month according to family stories—and managed to stay at Stehekin for three years and then seasonally for most of the rest of their lives.

McConnell introduced this larger region to readers of the Sierra Club Bulletin in 1956:

Hidden behind the lesser ridges of the rocky spine of northern Washington lies the nation’s finest alpine area and one of its most untouched primeval regions, the Cascades Wilderness. Here, entwined in the crest of the Cascade Range, is a land of high peaks, deep valleys and rushing water. It is a land of dark forests and shining glaciers, of fierce torrents and placid lakes, of dense almost impenetrable undergrowth and of open flower-strewn meadows, of sunlight and shadow. It is a sanctuary, one of the country’s last and perhaps its greatest.

Clearly, he had become a partisan of place. If it was half as nice as McConnell described, it must be a paradise.

Moving to this place (even just seasonally), McConnell told an interviewer in 1982, became “an ultimate commitment to the region that has been almost central to my life.”

Finding Conservation as a Political Scientist

McConnell soon discovered that it was hard to make a living in a town like Stehekin—no roads reach Stehekin even today. War had interrupted his graduate study in political science, so he decided to resume it at University of California, Berkeley. He wrote on agricultural policy, published it, and joined the faculty there (before moving on to other institutions later in his career).

Then, McConnell faced the dilemma of any new professor: the next project. Although McConnell had climbed mountains as a youth, he had not developed a strong interest in conservation. He noticed, though, a conservation campaign over dams proposed for Echo Park in Dinosaur National Monument. This was a significant moment in history, something historian (and my friend) Mark Harvey called “the birth of the modern wilderness movement.”

Intrigued, McConnell turned his attention to the conservation movement as something worth studying, but his personal connections in the North Cascades kept intermingling with his scholarship.

From the mid-1950s through the mid-1960s, McConnell published a series of articles about conservation and included a section on it in his landmark book Private Power and American Democracy (1966). McConnell argued that a “cult of decentralization” characterized American conservation agencies where local officials of, say, the US Forest Service mainly did the bidding of local elites.

Decentralization and localism, theoretically, countered the tendency of government power and responded to local needs. What McConnell found instead was administrative agencies facilitating the accumulation of private power. Or put more plainly, the American system allowed public power to serve private ends.

The political scientist did note that the American Progressive tradition worried about excessive private power and offered a counter: government regulation, if it could be deployed. Small interest groups gathered within conservation, each of them with narrow interests (e.g., soil conservation, wilderness preservation, wildlife). They were too diffuse to mount a counter to the materialistic values that dominated American conservation.

But this was beginning to change; such groups could be effective.1

Finding Activism for the North Cascades

In 1955, McConnell spent his summer as usual in Stehekin. Rumors surfaced that the Forest Service planned to sell timber from the Agnes Creek valley. McConnell investigated.

That same summer three backpackers—Polly Dyer, and Phil and Larua Zalesky—were investigating the area, concerned not only about potential timber sales but also mining in an area supposedly protected from commercial exploitation. They meandered into Stehekin, bumping into Jane, who told them, “You have to meet Grant! He’s trying to stop logging in the Agnes and Stehekin Valleys.”

They did not meet that day, but soon they found each other and like-minded Northwesterners who were determined to stop the economic exploitation of the North Cascades. By 1957 they formed the North Cascades Conservation Council (N3C), what McConnell once described as a “thin” group, “just a handful of people.”

In the Sierra Club Bulletin quoted above, McConnell made a case. The first, and biggest, element of it was the splendid, unparalleled beauty and natural history of the North Cascades and Glacier Peak Wilderness in particular, something driven home by accompanying photos by Philip Hyde.

Then, McConnell explained how this superb wilderness was as “yet uncut by roads, almost wholly undisturbed by commercialization.” This was mostly an accident of geography and history. Getting any commercial resources out of these distant areas was difficult; however, demand for easier access to the resources was growing in the 1950s.

“A region as splendid as any in the nation, one unique in alpine character and beauty, has by accident been preserved as real wilderness,” he wrote. “It remains to be seen whether the intelligence of man can do as well through policy.”

In 1956, when McConnell wrote those words, policy tools remained rudimentary for conservationists like him and his allies. Public consciousness about the area remained muted, and national values favored development.

But when you love a place, you don’t think much about odds.

McConnell heartily joined the campaign that led to the creation of the North Cascades National Park Complex in 1968. Dyer, who served with McConnell on the board of N3C for decades, credited McConnell in large part for it.2

Of course, a campaign like that, which lasted for more than a dozen years, includes many authors, but surely McConnell counts as among one of the leads.

This memorial in Political Science & Politics offers a nice assessment of his life and work. I also summarize this argument in a bit more length in my book, An Open Pit Visible from the Moon, p. 63-65.

The details of the campaign are best found in Lauren Danner’s book, Crown Jewel Wilderness.

Thanks for this account, beautifully written. Particularly the phrase "a partisan of place" and the line, "When you love a place, you don't think much about odds."

I enjoyed reading this, Adam. McConnell always seemed to be a grounded, logical, rational thinker. He was certainly passionate, but I admire the way he deployed his academic analysis and understanding of politics to the North Cascades issues. His letters to Brower and others clearly demonstrate his ability to see the big picture and diverse perspectives.