Although I decided to leave the professoriate three years ago, I remain interested in the intellectual, disciplinary, and institutional matters that affect higher education. Politically motivated attacks have undermined public support, and the challenges posed by technologies like AI are threatening and eroding its best principles.

These issues, however, never remain contained within ivy-covered walls. They are part of the broader culture. This week for The Library, I read a Loren Eiseley essay, “The Illusion of the Two Cultures,” that got me thinking about the humanities—and humanity. Read on!

The “Two Cultures” Argument

In the 1950s, a British scientist and novelist, C. P. Snow, presented his idea that two cultures operated in the British educational system. These cultures separated science from the humanities and arts. In articles, lectures, and books, Snow argued that a widening gap existed between practitioners of science and the humanities.

Snow characterized it like this:

Literary intellectuals at one pole—at the other scientists, and as the most representative, the physical scientists. Between the two a gulf of mutual incomprehension—sometimes (particularly among the young) hostility and dislike, but most of all lack of understanding. They have a curious distorted image of each other. Their attitudes are so different that, even on the level of emotion, they can’t find much common ground.

At the time Snow wrote this, he saw British leaders as woefully ignorant of science and technology, placing them at a disadvantage for provided policies to govern the sorts of issues raised by atomic weapons, the space race, and a whole host of other rapidly changing challenges. He encouraged the educational system to bridge that gap.

Foundations of Criticism

Any stark dualism like that described in “The Two Cultures” is bound to be criticized, and Snow’s was.

Scholars then and since responded by maintaining that scientific and literary culture were not so starkly opposed. Others questioned Snow’s rather uncritical acceptance of technological progress. Snow did not seem to anticipate the emergence of many interdisciplinary fields, either. His Anglo-centric view also missed some educational traditions around the globe not nearly so hidebound.

I’m not nearly knowledgeable enough to judge Snow’s argument in its entirety or the critics who pointed to holes in his framework. However, it seems indisputable that some gap exists, and we are poorer for it. Especially, I’d say, when institutions—universities, governments, media—tilt in favor of one of those cultures. The prestige of science (marked by salaries or investments) thoroughly dominates American institutions. And that’s a problem.

Loren Eiseley’s Reaction

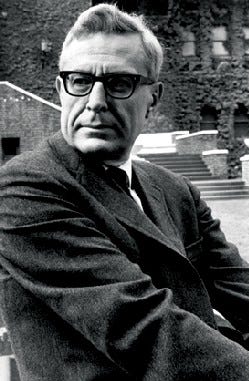

Loren Eiseley, like Snow, was a scientist—a paleontologist—and a gifted writer, so he was a perfect person to react to the two culture argument. By his essay’s very title—“The Illusion of the Two Cultures”—you can sense his criticism. But knowing a bit more about it is helpful.

Eiseley’s essay appeared in his 1978 book, The Star Thrower, whose title essay is probably his most famous piece of writing, but originally it appeared in The American Scholar in 1964, a tense period in Cold War history.

Eiseley recounts from personal and historical examples the myriad ways he finds scientists dismissing creativity and imagination, the “human realm” opposed to “the world of pure technics,” and arts and literature as “impractical exertions” often in “sneering” tones. He attributes this attitude to professionalism that emerges within an “Establishment” with its “behavioral rigidities and conformities,” something that affected those in the sciences and other fields (but more rarely—and without the access to the power that had accrued to scientific institutions). Standards stifle original thought, marinating in a stew of dogmas.

This kind of dismissiveness and conformity was, Eiseley thinks, only true of inferior scientists. He cites Einstein, da Vinci, and Newton as scientists who showed “a deep humility and an emotional hunger which is the prerogative of the artist.” What Eiseley has in mind in his critique were the others:

It is the lesser men, with the institutionalization of method, with the appearance of dogma and mapped-out territories, that an unpleasant suggestion of fenced preserves begins to dominate the university atmosphere.

Eiseley’s argument here becomes twofold. One, there are two cultures, but only when “narrow professionalism” is allowed to prevail in institutions, where “small men” fight to protect their small area of dominance. Two, to do the real work of the world, that work of highest value, there can be no separation between the work of science and technology and the work of letters and art.

Eiseley’s Stone

Early in the essay, Eiseley describes himself sitting at his desk stuck while writing about literature and science when his eyes found a stone in his office. No ordinary stone, this piece of flint had been worked hundreds of thousands of years before by a human ancestor. It formed a hand axe, a tool of great practical uses, a piece of essential technology. Eiseley thumbs the yellow stone, thinking about the essay on art and science he was trying to write, when noticed something: an embellishment.

It strikes Eiseley powerfully. The toolmaker “had wasted time” striking the flint again and again “with an eye to beauty” and not just getting the tool to work best. This was the blending of science and art, the one incomplete without the other.

Eiseley concludes, “Today we hold a stone, the heavy stone of power. We must perceive beyond it, however, by the aid of the artistic imagination, those human insights and understandings which alone can lighten our burden and enable us to shape ourselves, rather than the stone, into the forms which great art has anticipated.”

Application to the 2020s?

Near the end of his essay, Eiseley asks, “Have we grown reluctant in this age of power to admit mystery and beauty into our thoughts, or to learn where power ceases?”

It’s a reminder to those too mired in the petty struggles of institutions—universities, governments, businesses—that if you focus merely on the tool, the process, the short term, the power, you miss what makes us human, what makes life wondrous.

The goal of learning, he notes, was our personal evolution, the ability to know and change ourselves and not simply building tools.

Headlines boast of the next AI application or the astronomical sums being invested in developing technologies. All the while local newspapers are shuttered, museums reduce hours, and libraries struggle to stay open. Meanwhile, some in and near power in our time seem to dismiss ways of knowing the world outside brute objective force.

It is time to remember that common good should be elevated above brute force, to recall that values rooted in the best of humanity cannot be dismissed as irrelevant.

Closing Words

Relevant Reruns

This older newsletter connects to higher education. This essay, “When You Know the Price of a Huckleberry,” describes some of my thoughts about education.

New Writing

Nothing to share now, but work and ideas are percolating.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

The Wild Card comes around next week. Stay tuned!

Thanks for this wonderful, timely essay, Adam. I went immediately from this essay to your linked Huckleberry essay- which takes these current contemplations, and your readers, even deeper. What a treat- Loren Eiseley to Thoreau to Leopold to Carson, all beautifully woven together. 🙏

Well done Adam!

"[T]o do the real work of the world, that work of highest value, there can be no separation between the work of science and technology and the work of letters and art."