Last week‘s edition of The Field Trip reported on Northern State Hospital, the grounds of which were designed by the Olmsted Brothers landscape architecture firm. For this week’s version of The Library, I decided to focus on the brothers’ father, Frederick Law Olmsted.

I own a book that collects many excerpts of his work, Writings on Landscape Culture, and Society. This seemed a perfect way to learn about a leading thinker and practitioner of landscape and place. To guide my way through the almost-800 pages – and to focus the task – I decided to read a handful of related pieces: those focused on college campuses. I learned about landscape and design and a bit about education, too. Read on!

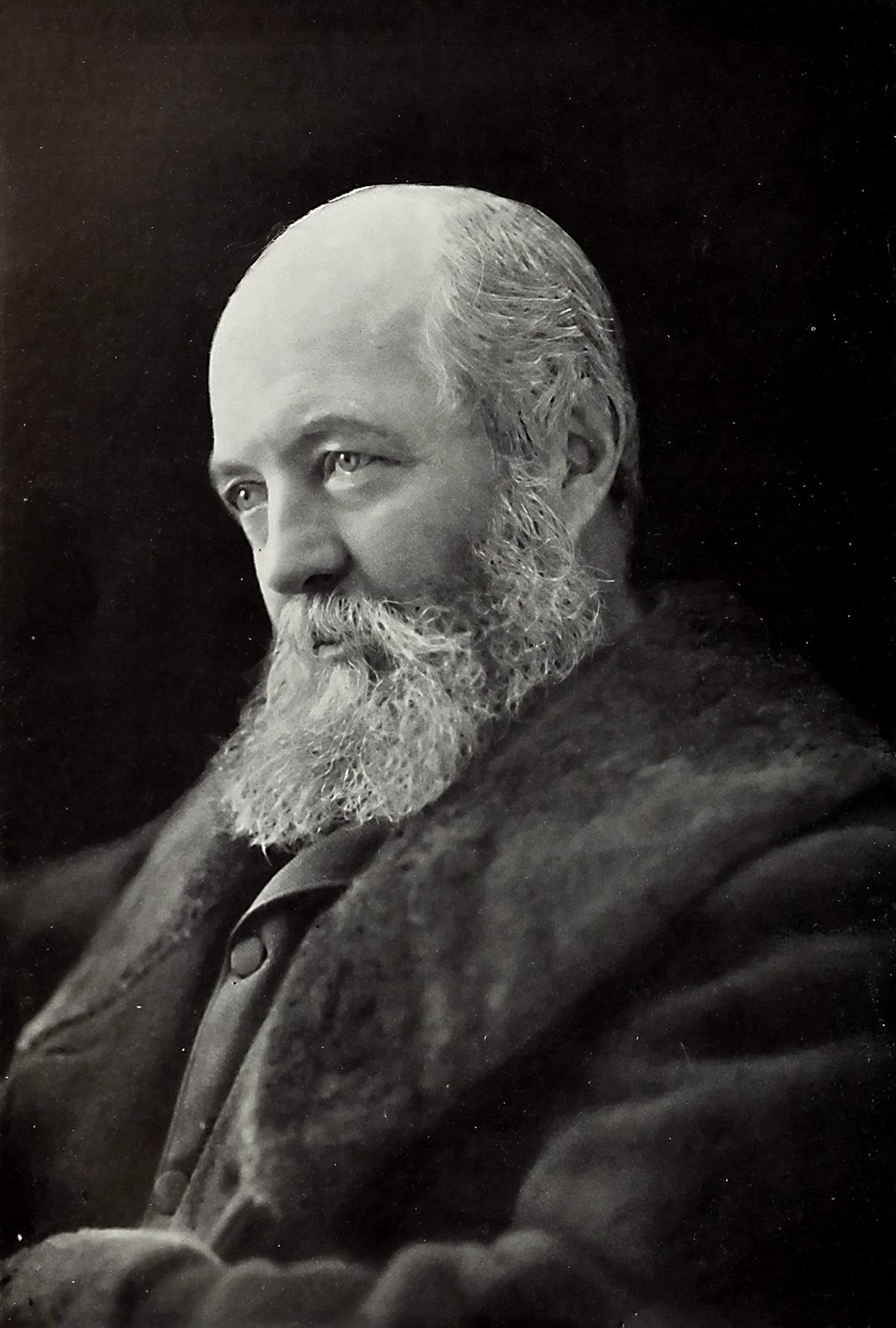

Frederick Law Olmsted

Olmsted (1822-1903) grew up in the northeast. His father enjoyed nature and instilled this in his son. Although his later career overshadowed it, Olmsted began as a journalist and wrote several books about the antebellum South. Later, in the Civil War, Olmsted served as the executive secretary of the US Sanitary Commission, a forerunner of the Red Cross.

All of this might have been sufficient for a useful life, but Olmsted distinguished himself as a landscape architect, perhaps the founder of this design approach. His fingerprints touch many parks and plans across the United States, including places as famous as New York City’s Central Park or the grounds surrounding the US Capitol Building.

Besides the Civil War, many other reforms in the 1860s brought long-lasting significance to the nation. In 1862, Congress passed the Morrill Act to develop colleges in every state “for the benefit of agriculture and the Mechanic arts.” We know these as land-grant universities. (For a deeply researched project that interrogates how this program functioned for Indigenous peoples and their lands, see Land-Grab Universities.) This is the essential backdrop to some of Olmsted’s most interesting writing about designing college campuses and environs.

Integrate Outdoors

A key element to maybe all of Olmsted’s designs was to integrate the outdoors into daily life, to lift up the natural (even if that meant manufacturing it or erasing humans and their histories from the scene).

In 1866, he produced a report about how to best situate Berkeley, where the University of California was planned. Much of Olmsted’s concern emphasized the neighborhoods surrounding the campus, believing that for the college to survive and for scholars to “be prepared to lead . . . the advancing line of civilization,” it would be necessary to create “a neighborhood of refined and elegant homes.”

Olmsted thought distant, pleasant views were important. But he also demanded that homes (and the college) include accessible outdoor spaces where inhabitants could be rejuvenated regularly. Good health demanded it:

[t]he frequent action of free sun-lighted air upon the lungs for a considerable space of time is unquestionably more important than the frequent washing of the skin with water or the perfection of nightly repose.

There you have it: Fresh air was more important than baths or sleep!

Grounds as Models

Idealistic, Olmsted thought ground plans, properly implemented, created spaces that would influence those who lived among them. Central Park would provide a respite for anxious New Yorkers, and college grounds could cultivate good habits and character. The grounds themselves, the layout of buildings and the design of open space and gardens, reinforced lessons for citizenship. No haphazard design here.

In writing “A Few Things to Be Thought of Before Proceeding to Plan Buildings for the National Agricultural Colleges,” Olmsted recognized the college-aged tendency for goofing-off. Or, as he put it more delicately: men and women possessed a “natural disposition . . . to diversion.” Consequently, he thought it wise to encourage “a daily exercise of this disposition at home in any way that shall be altogether healthful and healthfully educative.” A college campus should do the same. Make sure there are gardens, not taverns, for instance. In fact, when writing to the board of trustees in Maine, Olmsted argued that the library and gardens were the two most important components to ensure that students established “certain tastes and habits” to meet the needs of citizenship.

To Olmsted, the mission of education could be promoted, or thwarted, through the physical space (something that is entirely neglected in our virtual educational spaces). Without taking care of the ground plan, Olmsted thought, the entire project would become mired in confusion and inefficiency.

Unity and Harmony

You can easily date the expansion of most institutions by observing the changes in architecture. This part of campus contains the original brick buildings; that part of campus that looks like a concrete block came in the postwar era; over there, in shiny glass, is the newest building looking like a corporate office park.

For Olmsted, this would be anathema. In sketching out a campus plan for Edward Miner Gallaudet, the first president of Gallaudet University (known from 1864 to 1894 as the Columbia Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb and Blind), Olmsted repeatedly emphasized the need for harmony. The grounds and the architecture needed to be composed as “one harmonious whole,” he wrote.

Writing to someone associated with Cornell University, Olmsted pressed on him the need to “secure picturesque unity.” Properly, a campus would appear integrated.

Conclusion: Long-term Thinking

I enjoyed reading these letters and reports and the feelings of familiarity and surprise they elicited. I spent a great deal of my adult life on college campuses (four years of undergraduate education, six years of graduate education, twenty-two years of teaching). Olmsted’s idealism about the purpose of forming good character and habits to produce citizens resonated with what I think is the best of college. His emphasis on the grounds themselves made me reflect, too.

We spend a lot of time and money now on technologies in the classroom and beyond. Maybe most campuses still have garden- or park-like spaces, but often you have to trudge to get there. Stately trees and expansive lawns are nice. Gardens would be, too, where the intellectual could add to the ornamental.

My final years teaching, I walked from where I parked my car to my office (and the reverse) through the campus’ original arboretum. I know it did me well.

A final point that seems wonderful and different from Olmsted. Writing about Cornell in 1867, Olmsted warned that if the board of trustees continued with its ill-thought plan, they would have to demolish some of the buildings “within two centuries” to keep the design line right – something he thought terribly shortsighted. I can’t tell you how much I love someone thinking that having to change two centuries hence would seem hasty.1

Reminder: Through August, you can get a paid subscription at 20% off, and you can use that as a gift for others.

Final Words

While teaching, I spent plenty of time thinking about the role of education. Although I didn’t spend any time contemplating landscape architecture, I did think about setting. One personal essay explores that; see “When You Know the Price of a Huckleberry,” from Weber—the Contemporary West.

In other writing, I reported a piece last week for a local news outlet. It relates to my newsletter from a couple weeks ago about zoning. Check out my story, “Finding Happily Ever After in Skagit’s Ag Zone,” in Salish Current to see how zoning practices are shaping a local controversy.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

Next week, The Wild Card returns, and as of this writing, I have no idea what I’ll dip into. Stay tuned!