You never know what you're going to get in January in the Pacific Northwest. Snow or rain, damp air that seeps through every layer of clothing, even warmish sun on occasion. Planning The Field Trip in such an intermittent climate feels risky. But the risk of being caught without a raincoat or a down vest or sunglasses is minor compared with disasters and beauty that can visit us on any given day. Read on!

The Everyday

The culture of nature that influences many of us celebrates the monumental, the majestic, the magnificent. We have been taught to praise the high peak. We know we are supposed to lose our breath watching the sun dip into the horizon with no buildings in our view. We praise the superlatives – largest wilderness, biggest herd of wildlife, longest free-flowing river. I'm as guilty of this as anyone.

I went out recently for a walk with friends. Wild places thread through all our professional and personal experiences and identities. But on a winter weekend day, daylight is limited, and other obligations meant we could devote only a few hours to being outside. The hike's reason was friendship and time in the trees, not to tap anything untrammeled. Nonetheless, morsels of beauty and delight scatter along such a walk if you remain open to it.

Upriver and Upslope

I live near the edge of a watershed and daily watch where the Skagit River empties into Skagit Bay. But for this trip, we crossed over one drainage to the south and headed upriver where the waters of the Stillaguamish River still gather. Our friends guided us to a trailhead, really just a gated, overgrown road. No signs pointed the way or identified whose lands these were (a mix of public, private, and Tribal). The roadbed stretched wide enough to accommodate ATVs (minor signs along the way) and made it easy for dogs and conversations to run freely.

This is western Washington and January, so green dominated everywhere. Conifer stands spread beyond the roadbed, ferns fluffed out below, and mosses clung to almost everything that didn't move. At a ravine, a ribcage of a deer (I presume) warned about careful footing or predators or hunters. We observed and turned and climbed, reaching the top after about a 500-foot elevation gain. Easy enough work for a midwinter Sunday.

Atop a plateau, we walked through woods for a while. Big stumps set back from the path offered occasional reminders that these tall trees were comparatively young, growing in the historical shadows of a forest with much bigger trees. Guessing, the trees we walked through started growing about the time I did half a century ago. The forest likely had been cut twice already. Old-growth forest it was not, as those chunky stumps silently pointed out.

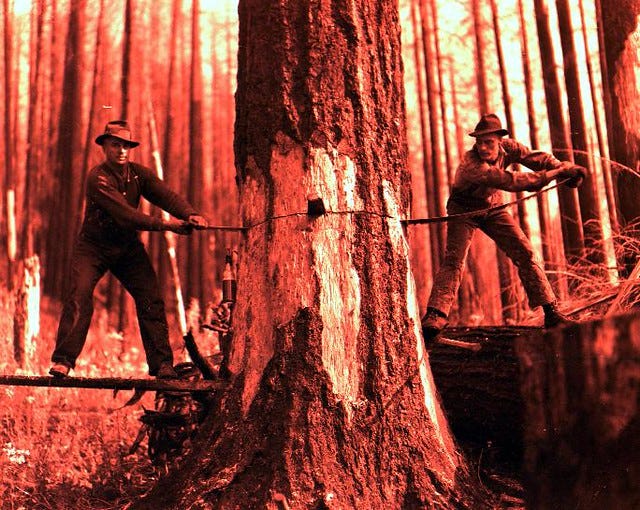

Seeing those types of stumps brings me mixed thoughts and feelings. They remind me of history. I think of men standing on planks stuck into the notches still visible that put them high enough to saw through the thick trunks. This represents a heritage that any historian can appreciate. The stumps also remind me of a differently scaled forest: that is to say, bigger trees with greater gaps between them. And, all things being equal, I'd rather be standing before a trunk than a stump. But my desk is made of wood. So is my house. Life's complicated.

A few turns, a last straight shot, and the road ended abruptly.

Sliding into Tragedy

Midmorning on a Saturday in March 2014, the hillside gave way. The mud and debris covered a square mile below. In a tragic convergence, it hit a densely packed neighborhood in what is otherwise a sparsely settled valley. In total, 43 people died and 49 homes and buildings destroyed. This slide is the deadliest in US history.1 The debris dammed the Stillaguamish River, which backed up and flooded the main road, which remained completely closed for a couple months and only reopened in full six months later.

The event riveted attention to a place normally ignored. Hundreds of people descended on the tiny community of Oso, just downstream, for search and rescue and recovery operations. The aftermath included, predictably, finger pointing. The site was known to be unstable, making some wonder why development was allowed. Some thought logging weakened the soil. But rains were at 200% normal, and geological examinations throughout the valley show a long history of slides. Sometimes, the earth moves.

Several years ago, I stopped at a memorial along the highway and viewed the slide from below. The view from above offered much better perspective.

Beauty Even Here

The road ended. The forest opened up because trees can't grow in air. I walked to the edge. It's irresistible. And seemingly safe. At the precipice a homemade cross leaned back as if observing all.

We arrived at a moment when fog covered the highway and almost obscured the river, somehow appropriately hiding the memorial below while we oriented to our spot at the edge.

The earth had just slipped away. Below, pockets of water formed. The river has changed course since 2014. Big berms that look engineered are remnants of the force of the slide. Bush and trees have grown back in some places, not in others. Full trees with rootball intact lay on their sides, halfway down. Grays and browns and greens and yellows and even some reds circle the bowl that remains. The river's blue winds through the scene.

After a few minutes of mostly-silenced awe, the fog lifted and the clouds momentarily opened for a glimpse of the mountains across the valley. A snow-topped Whitehorse Mountain peeked through for a brief time. Then, the clouds collapsed again.

We snacked and talked. About memories. About culpability. About governments. About logging.

Someone who lived below and a ways downstream drove up on an ATV with his brother, interrupting our musings. The driver had discovered the spot the day before for the first time and wanted to show his brother, who awkwardly shuffled between us to look out, in silence. After a few minutes, they climbed back aboard and buzzed away.

The spell broke, but the weather still hadn't. We packed up the crackers and shook off the experience.

Sublime

On our way down, we looked around and realized that we were walking in a slide from hundreds, or thousands, of years before. Sometimes, the earth moves.

And sometimes it moves you with its beauty and power.

The word sublime captures this. Look it up and you'll find that sublime means "tending to inspire awe." But don't stop there. Look up awe, too. You'll find its archaic meaning is "dread." Its non-archaic meaning calls it an emotion that combines "dread, veneration, and wonder." Most of us, I assume, rarely combine such emotions into one. Who dreads and wonders simultaneously? And yet…

Somehow, it is apropos, looking down, shades of so many colors, mountains across the valley echoing back sounds and the sights. Sublime it is.

Closing Words

Although I often taught about disasters, I have not written about them with great detail. However, I have written extensively about forests. This article of mine (adapted from this book) tells the story of a forest ranger working not too far from this site for something he may well have considered sublime. Check it out!

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

We move to The Library next time, and I’ll be diving into a recent classic about forests in Washington. Stay tuned and meanwhile, please consider sharing Taking Bearings with people who might enjoy it. Word of mouth helps grow the reader base.

This is the deadliest slide on its own, not counting slides that were part of other events (e.g., volcanic eruptions).