Without much going on in the news over the last week, I randomly1 chose this week’s topic for The Classroom: the corruption of Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall and the Teapot Dome scandal. The idea just came to me, unprompted by current events.2 Read on!

Conserving Valuable Resources

The American conservation movement reached prominence at the turn of the 20th century. Although it included many concerns, ensuring resources would last for industrial uses was high among them. Conservationists saw this as a way to ensure permanent prosperity for Americans.

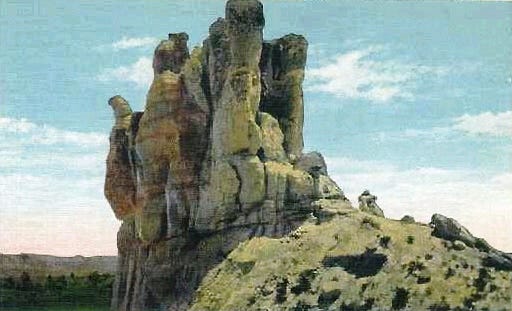

As part of these efforts, the federal government set aside a coal reserve in Alaska and two petroleum reserves, one in California and one in Wyoming in the 1910s. Odd geological features in Wyoming earned it the name Teapot Dome. These reserves were meant for and controlled by the Navy. Conservation, in this manner, was tied closely to national security.

Many Americans and most westerners saw such natural resources as their birthright and the ticket to economic development. Setting aside reserves, even for future military purchases, sparked controversy.

And they proved tempting for unscrupulous people.

Harding Administration and Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall

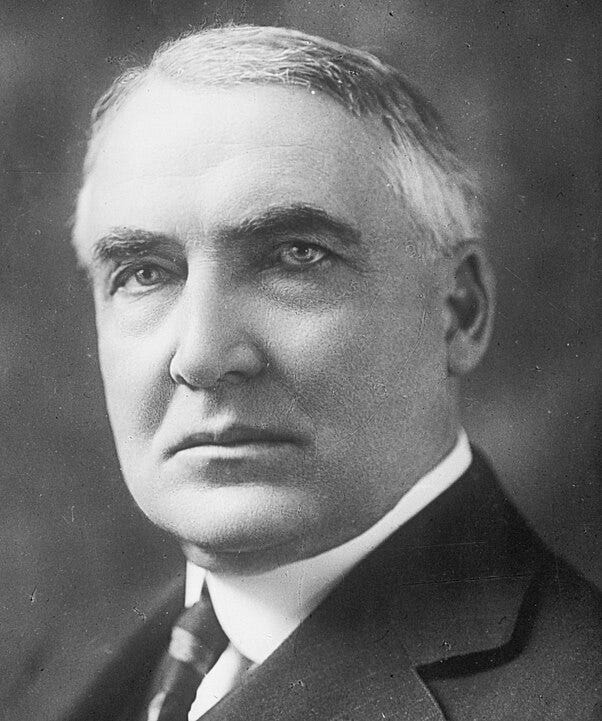

President Warren G. Harding was a popular Republican president, but after his death in 1923, just two years into his presidency, a series of scandals were revealed that tarnished his image.

In some ways, Harding recognized he had only himself to blame, because he surrounded himself with friends. And that was a problem:

I have no trouble with my enemies. I can take care of my enemies all right. But my damn friends . . . my God-damn friends . . . they’re the ones that keep me walking the floor nights.3

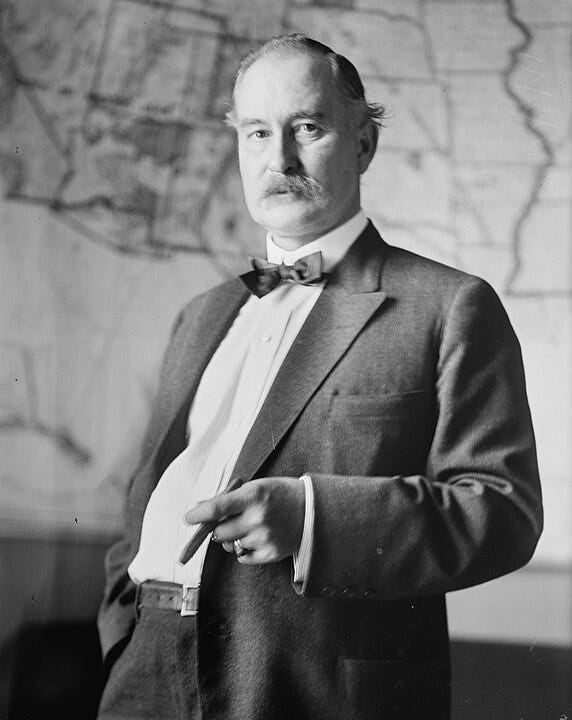

One of those friends, who he invited into his cabinet, was Albert Fall, Harding’s secretary of the interior.

One of my mentors, Peter Iverson, wrote vividly about the secretary: “Albert Bacon Fall chewed cigars, did not like the presence of the federal government in the West, and held American Indians in something other than high regard.” Not missing a beat, Iverson added: “He was, therefore, the ideal person to become secretary of the interior during the administration of Warren G. Harding.”4

Although born the first year of the Civil War and raised in the South, Fall later moved West and settled in New Mexico. He practiced law and became a politician. Suiting a man of that social class and ambition and locale, he purchased a large ranch near Las Cruces.

When he became one of New Mexico’s first U.S. Senators, his desk was next to Harding’s.

A man of deep “principles,” Fall had first been a Democrat and then became a Republican. Once, he called for abolishment of the Department of the Interior and then became its Secretary. And after he became secretary, he sought more power and influence, including an attempt to grab control of the Forest Service, which is housed in the Department of Agriculture. He also stripped millions of acres from the Navajo Nation after oil was found in its lands. He ran too many sheep on his Forest Service allotment.

In other words, Fall followed his own rules for maximum personal convenience.

Like many westerners of the time—and since—Fall believed resources were meant for use, now, without much concern about the future. “All natural resources should be made as easy of access as possible to the present generation,” said Fall. “Man can not exhaust the resources of nature and never will.”5 (This, of course, is incorrect.)

Conservationists like Gifford Pinchot also thought resources should be used, but Pinchot thought they needed to be managed to last for the long run. Pinchot, the first chief of the Forest Service had little good to say about Fall being interior secretary:

On the record, it would have been possible to pick a worse man for Secretary of Interior, but not altogether easy.6

Teapot Dome

The New Mexico ranch Fall bought overextended his finances. Fortunately for him, his acquaintances included generous men in the oil industry, including Harry Sinclair and Edward Doheny.

Fall was in a position of need, in a position of power to help Sinclair and Doheny, and lacked any pesky scruples.

On taking office, President Harding transferred the Naval Petroleum Reserves from the Department of the Navy to the Department of the Interior—at Fall’s behest. Then, Fall leased the reserves to Sinclair and Doheny’s enterprises without putting it out to public bid. Both the transfer and the leasing were done secretively.

Meanwhile, just before the leases were extended, Doheny “loaned” Fall $100,000, delivered in a little black bag. Sinclair purchased a third share in Fall’s ranch for nearly a quarter of a million dollars. And Fall received $200,000 worth of bonds from Sinclair.

Congress investigated after this all became public, and President Calvin Coolidge appointed special prosecutors.

To be clear, at issue was not the leasing or exploitation of the oil reserves; at issue was the corruption.

Aftermath

The investigations ended up with Fall spending 10 months in jail and paying a hefty fine. Fall was the first cabinet secretary convicted for activities done in office.

After his imprisonment, Fall quietly moved to El Paso where his wife opened a restaurant to support the household.

Doheny and Sinclair lost their leases but were otherwise not punished.7

In the Supreme Court case that voided the leases, Mammoth Oil Co. v. United States (1927), the Court wrote,

As is usual in cases where conspiracy to defraud is involved, there is here no direct evidence of the corrupt arrangement.

These are words that might be worth remembering.

Closing Words

Relevant Reruns

In the 19th century, railroads often were vehicles of corruption as much as transportation. This earlier newsletter provided some of their history. For a while, I published a column, “Reckoning with History,” for High Country News. My first one focused on corrupt interior secretaries; you can read it here.

New Writing

Summer is here and that means farmers markets and farmstands are open. I have written two stories about this. The first appears on a local nonprofit’s website. (Next week, the other will be available.)

A year ago I was ask to write something for a theme issue on Historians and their Audiences for Pacific Northwest Quarterly. It appeared earlier this spring. You can read my thoughts about “Being Historically Faithful in Public” here.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

The Field Trip is back in the cycle next week, and I’m hoping the rain finally stops so I can enjoy an outing without rubber boots! Stay tuned!

It was not random!

Of course, it was prompted by current events!

Michael E. Parrish, Anxious Decades: America in Prosperity and Depression, 1920-1941 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1992), 12.

Peter Iverson, Diné: A History of the Navajos (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2002), 133.

Sarah Deutsch, Making a Modern U.S. West: The Contested Terrain of a Region and Its Borders, 1898-1940 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2022), 248.

Ibid., 251.

In future years, operators in the field complained about the layers upon layers of checks when working with the government. Part of that was a result from Teapot Dome.