For this week’s Wild Card issue, I finally have brought in another voice to Taking Bearings—something I’ve wanted to do for some time. I hope you enjoy the conversation below.

Introduction: Laura Pritchett

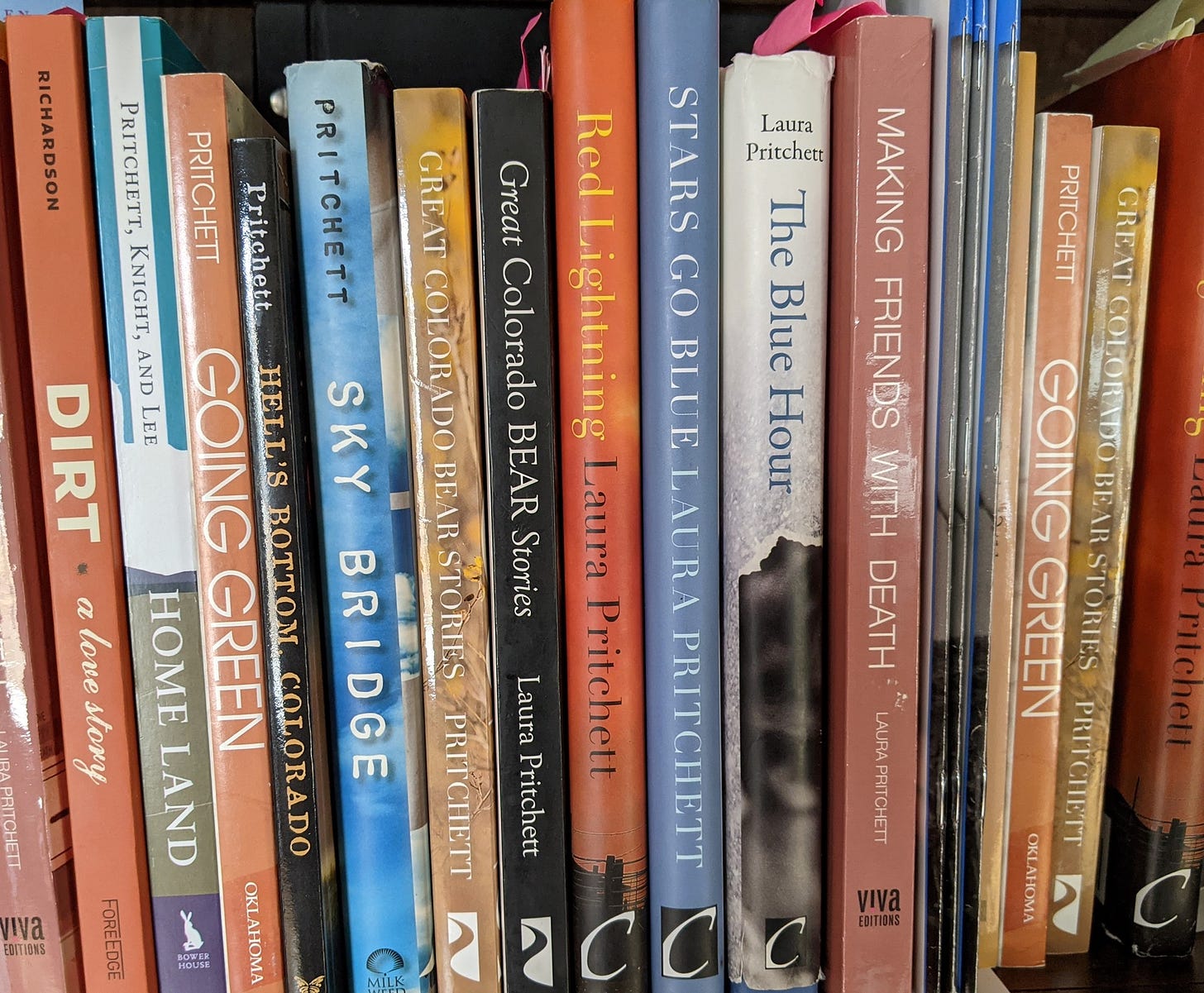

Besides being my friend and a writing mentor, Laura Pritchett is an author and teacher extraordinaire. She has published hundreds of stories, essays, and articles. Her five novels and two nonfiction books—all terrific—mostly center on lives in the American West. This is also true of her two forthcoming novels, Playing with {Wild}Fire (Torrey House) and The Keys (Ballantine). Laura heads the MFA in Nature Writing program at Western Colorado University. She is rooted in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado, an unmistakable influence for her prose.

The Conversation

Over the course of a couple weeks, Laura and I exchanged ideas through email, riffing off one another. The “conversation” appears below. Read on!

On Sense of Place

Adam:

We met through Fishtrap, an organization based in the stunning Wallowa Mountains of northeastern Oregon that sponsors several literary programs throughout the year. Those programs are meant “to promote good thinking and clear writing in and about the West.” In my newsletter, I aim to reflect on “place, history, and writing.” There’s overlap there, I hope.

And I think I’m correct in saying that you and I share a deep love of and fascination with the West and with place as a central theme in our work. Can you help me understand how you see sense of place functioning in your writing and writing you admire?

Laura:

Sense of place. Ah, one of my favorite topics! One of my colleagues, CMarie Fuhrman, happens to be teaching one of my novels, The Blue Hour, right now in a class about mountains in literature. As an aside, let me just say that a) I’m honored, and b) we both teach in the Nature Writing MFA program at Western Colorado University—and we try to work in faculty books, if only because students should probably study one work of those who they’re learning from, ha! Anyway, she asked the students if my novel could be picked up and placed elsewhere, and I was delighted (and relieved) to hear all responses were basically “no way!” The mountain itself is a main character. The community that resides at its base are completely and truly influenced by the space, terrain, weather, creatures, light quality, you name it, of this particular place. That is true of my forthcoming novel Playing with {Wild} Fire too, which is set in a similar community.

All this is to say: I prefer books that could not be picked up and plunked elsewhere. Place is not merely setting. External landscape is absolutely related to internal landscape of characters—their thoughts, feelings, belief systems, love stories—all deeply intertwined. You can guess that given my job at Western, and my teaching at wonderful Fishtrap, that I am most interested in literature of place. It is my passion. Call it nature writing, environmental writing, or place-based writing, whatever—it is all primarily concerned with how a physical location alters and deepens our lives.

In my new novel, I’ve taken a new (to me) step—I have a mountain itself narrating a chapter, speaking of its long history as sea floor, as uplift, as weathered and eroded, as an entity experiencing the effects of climate chaos as it is burned in wildfire. So, yes, history. The context of time. History and place. Yes!

On Sense of Place and Sense of Time

Adam:

I certainly agree with the students at Western: your work is not easily transferred to some other random place!

I’m glad you ended where you did, because I am especially interested in how place intersects with time, with history. (As a historian, how can I not be interested in that!?) When I first heard the term “sense of place,” I didn’t understand it, and people trying to explain it didn’t help. The first time it started to sink in for me was during a visit to the Ak-Chin Indian Community in Arizona. Something about the many, many generations who lived in that place helped me begin to conceive of something like a “sense of place.” But that means for me that sense of place is always wrapped up with sense of time.

Is this just me? How does history work with—or against—place in your creative mind?

Laura:

Such a good question! And this touches on something I’m really fascinated with—the ways our brains work with time, or latch on to particular trajectories of time.

I remember you sharing an essay with the Fishtrap group, and you mentioned that when you go for a walk, you can’t help but experience the history of that place, too. Like, any ol’ hike, you’re thinking of a settlement or shift in policy or something regarding the human history there, and I thought, “Huh! I don’t do that at all.” Sure, I mean, vaguely—as in, once French trappers named the town I now live in LaPorte, because it was/is indeed a door to the mountains. I find that interesting, sure, but it doesn’t infuse my experience on a hike.

But my brain does do something else. While I don’t see human history so much, my mind often drifts to geological history, like, is that an uplift or a volcano? Or my eyes try to imagine a meadow back when it had beaver dams. But my brain (and I’m sorry to say this, please still be my friend!) rarely considers the human experience of a place.

More than anything, though, I tend to go forward in time. What I do find myself thinking of as I amble on some walk is: What is going to happen to this place? My brain—of its own accord, this is how it occupies itself, I guess—conjures up images of what it might look like in 100 years, for instance. I think this is the fiction writer in me: wondering about potential, imaginative stories. I also think it’s a signal of the advocacy side of me. Lordy, what’s going to come?

Intellectually, I understand the importance of knowing the history—we learn from history, we can respect history, we need to understand history. But my mind just darts to the future.

I will be the first to admit that this is some deficit I have. My sister, for example, is always trying to get me to care about my dead relatives, and I have little interest, which frustrates her to no end. I tell her, “I don’t want to be a dutiful descendant so much as I want to be a good ancestor.” That’s true, but mainly it’s a lame excuse—I just have limited time, and I’m pretty busy thinking about what’s going on now, and what is to come.

Which leads me to this: Her mind, and your mind, seem to naturally go back in time, though I know you care about the future too, after all! Are most humans able to move in all directions? Do you have any words of wisdom to help me deepen my experience of place?

On Using Story for a Just World

Adam:

Of course, I care about the future! What could be more important in the grand scope of the universe? Your idea of being a dutiful descendant is beautiful. I try to vote and behave in ways that will move on the trajectory that seems likely to thrive. When I taught, I hoped students would develop the capacity to think in these ways and, perhaps, take lessons they found in the past I tried to share with them. I hope my writing—at least occasionally—offers a new view to people.

To ponder about a better future, I think, we need all the tools available. For example, a comment from Barry Lopez in Horizon has stuck with me. He pointed out how Indigenous languages developed in places. That means how to live well in particular places is embedded in languages, many of which are already extinct and many still threatened. We can find clues for that better future in languages that evolved with particular ecosystems and relationships.1

I also remember reading an essay about biomimicry once. The author characterized it, essentially, as borrowing metaphors and analogies from nature and developing engineering solutions from them. Then, he took that concept further, saying, “Experimentation with new metaphors, through poetry, writing, and theater, can create shared visions sufficient to support cooperation.”2 If we are in a global environmental crisis, then all areas of exploration need to pitch in.

Poets (and historians) included! Metaphors matter!

My family were and are storytellers, so I’m sure my predilection for the past came from that. But studying history in books—what I did systematically for 30 years—eventually rubbed off so that I could no longer avoid its implications out on the land. The place I wrote about that you remember from above is a reservoir. Beneath it were Nez Perce villages that dated to thousands of years ago where families gathered and caught salmon that are now endangered. Then came farmers who grew fabulous orchards. They’re gone too, beneath a river stilled. I’m always wanting to know those layers of story.

But, if you read that essay, you’ll see my final line is about the future and my hope the dam will go away and the river returned.

It seems to me that we’re both—regardless of which direction we’re oriented—curious about just relationships to place. Would you agree with that rather grandiose characterization? And if so, how do you see something like writing playing a role in producing a just world for human and beyond-human communities?

Laura:

I love Horizon and that gorgeously-articulated point that Lopez makes. Indeed, language (and its plentiful metaphors) and place are so intertwined. I too am interested in the evolution of language. How, for example, we can begin to call our nonhuman friends more respectful names. Another example is how our auto-corrects are, at the moment, quite white. Both very “fixable” and would help create this more just world of which you speak! For sure, with the help of advocates, I think we’re heading in the direction of linguistic justice and awareness.

As far as stories creating a more just world, well, I think we can all agree on the importance of story in public policy and cultural evolution. I know it in my bones, but also, one fairly heady perspective is found in The Science of Storytelling by Will Storr, who points out that when we’re “lost” in a story, brain scans illustrate that our sense of self becomes inhibited, and there are changes in various neurochemicals. Psychologists call this state “transportation.” As he notes, “Research suggests that, when we’re transported, our beliefs, attitudes and intentions are vulnerable to being altered, in accordance with the mores of the story, and that these alterations can stick.”3 Indeed, he argues that the birth of novel—Pamela in 1740—inspired human rights, and that slave narratives of the 19th century are often regarded as the impetus for an enormous cultural shift. In short, writing creates empathy. As Storr puts it, “transportation changes people, and then it changes the world.” Which is only to say, this fiction writer, and you, the historian, know that it’s stories that engage and then change us.

So many of us are so deeply connected to place. Place. Time. Story. Those are the pillars of our life and work, perhaps?

Adam:

How could it be otherwise?

Thank you, Laura, for participating in this engaging conversation, helping me see this shared work of ours in better light. You are ever the teacher!

Laura:

As are you, Adam. May we keep growing and learning and deepening our connection with place and with language. Why? So that we may be better stewards of this miraculous blue ball we call home. Better lovers of life. Live the best and deepest lives, and help others do the same.

Closing Words

Please look up Laura’s wonderful writing and consider buying a book.

In our conversation, she mentioned an essay of mine she saw in draft form. It eventually was published in Wild Roof Journal as “Submerged Stories, Breaching History.” Go have a read!

And I’m excited to share that my most recent personal essay is out with Talking River Review. It’s called “Stones in a Stream” and is quite short — you could read it in under three minutes. I hope you check it out.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

Back to The Classroom next week. I’m not fully committed yet, but I think the next lesson will be focusing on how the federal government asserted power over rivers and some of the implications. Stay tuned!

As always, I’m grateful that you’re reading this. If you enjoyed this, press the Like button below or leave a Comment. If you are able, consider upgrading to a paid subscription. And if you know others who might enjoy this, share the newsletter with them. Thank you for reading.

Barry Lopez, Horizon (New York: Knopf, 2019), 80. Lopez was drawing off the work of K. David Harrison’s The Last Speakers: The Quest to Save the World’s Most Endangered Languages (Washington DC: National Geographic, 2010).

Bryan Norton, “Ecology and the Human Future,” in After Preservation: Saving American Nature in the Age of Humans, ed. by Ben A. Minteer and Stephen J. Pyne (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 82.

Will Storr, The Science of Storytelling: Why Stories Make Us Human and How to Tell Them Better (New York: Abrams, 2020).

Great dialog, Adam, so much so that I need to reread it and digest more!