The Transitory Nature of Local History

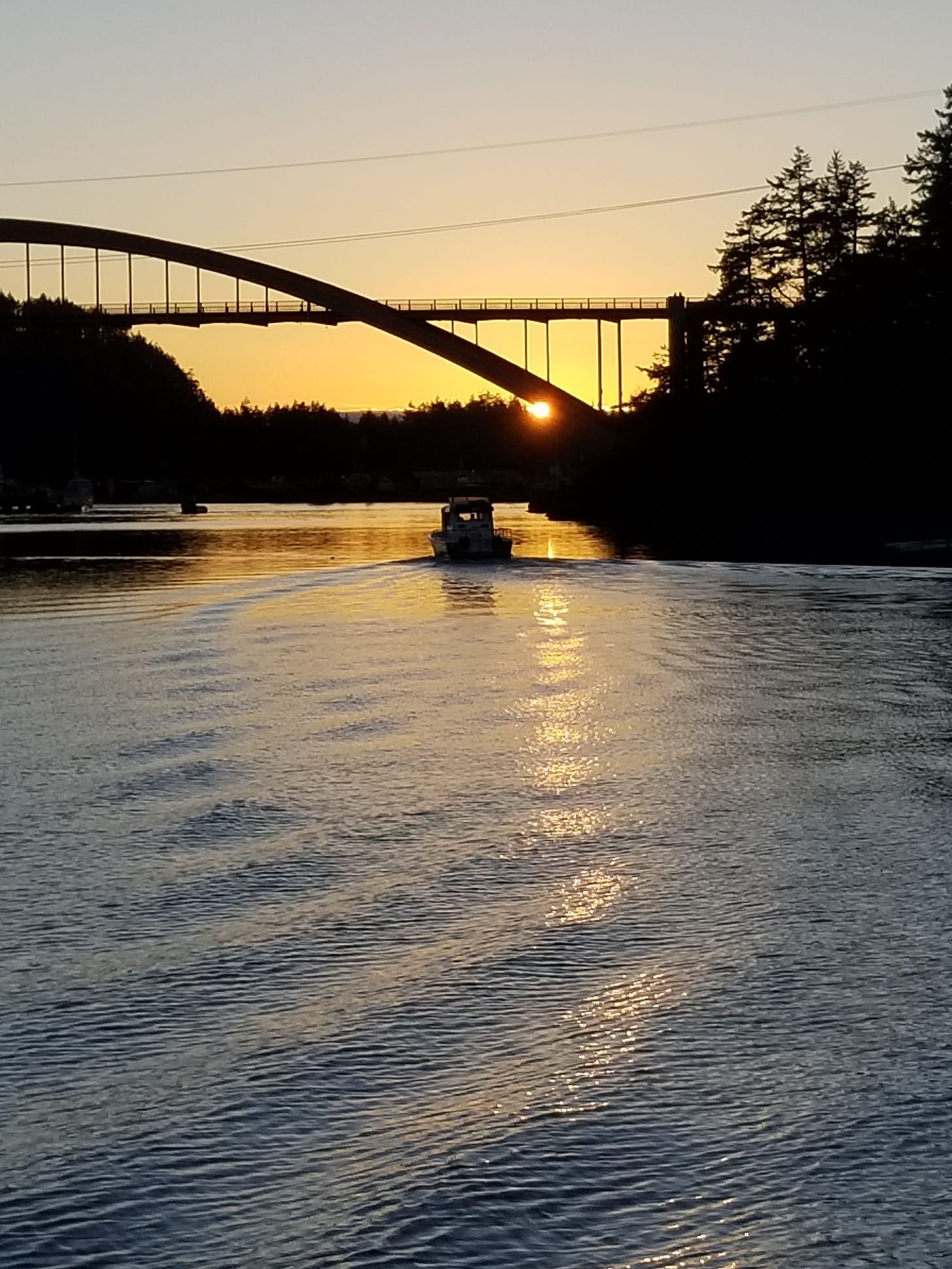

A trip to a local museum leads to musings on permanence and change

Almost exactly a year ago, I moved to Skagit County, a place I grew up near but that has a distinct feel (and history) compared to that childhood home. If you aren’t from western Washington, the only reason you’ve possibly heard of Skagit County is its impressive tulip fields. Do an internet image search for “Skagit Valley” and colorful flowers will fill your screen, along with an occasional river or mountain shot.

My year as a Skagit resident has seen me transition out of a university teaching career, but my daily work remains focused on writing history. I recently realized my sense of Skagit’s history remained superficial. So for The Field Trip issue of Taking Bearings, I headed to the Skagit County Historical Museum in LaConner, a quirky arts town a short drive from my home. I held few expectations–local museums always offer a wide range of resources and qualities–but I figured it might furnish me a useful introduction.

Western Towns and their (Commercial) Pasts

My history interests serve me well in such local museums, because my work as an environmental historian of the American West means I carry with me an interest in the ecological changes that can be easily displayed–and often are–in museums like this one.

Skagit County’s Setting

Skagit County runs from Puget Sound to the crest of the Cascade Mountains. The Skagit River, the largest stream that flows into Puget Sound, carries water from snow in the North Cascades. The lowlands near the coast are mostly flat and occupied today by farms, where towns have not taken over. This makes the strip along the sea seem particularly productive, but the foothills and mountains are forested and rich with plant and animal life, too.

Residents of the county, long before “county” was a meaningful jurisdiction, have always relied on the land’s–and sea’s and rivers’–productivity. The trick here, as it is anywhere, is to coax that productivity along the pathways that the local culture finds profitable. (Read “profitable” beyond a singular market focus.)

The part of the museum that fascinated me most displayed the transformation of Skagit County’s Indigenous landscape into an early market-based one. (Note: The Native peoples displays prohibit photography, so I am not recounting it here.)

(Absent) Larger Factors

The commercial landscape memorialized here zeroes in on local factors. This is as it should be for a county historical museum, of course. But any historian of the American West would recognize the fingerprints of the federal government in treaties, the military, harbor and river improvements, land laws that facilitated privatizing property and keeping some of it federal, and more. Instead of that 30,000-foot view, the museum gets down in the dirt.

Literally.

Local Factors

Commercializing the landscape started in the water.

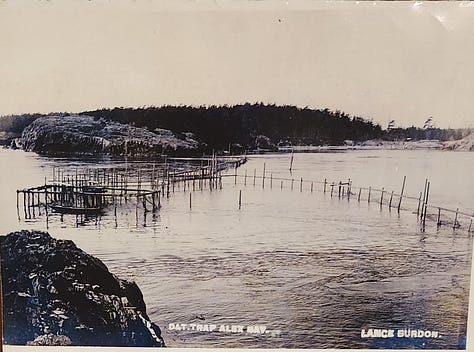

One of the first nooks in the museum that drew my interest included a model of a huge fish trap with some associated images that indicated how efficiently destructive these devices were. Images of slippery piles of salmon drove home the point. Besides the industrial-scale fishery depicted here, displays showed towns that grew up along the coast, places that no longer exist as communities, just open space. This emphasis on water reminded me how, in the days before automobiles–and even prior to trains–transportation focused on waterways.

Fish fed many in this place, but farms fell within a more familiar cultural script. But here, that required reclaiming land from water. The Skagit River flooded the lowlands regularly. The museum’s display on “Diking & Ditching” depicts the massive labor required to hold back the waves of Puget Sound and contain the flows of the Skagit. Only a few details can be shared in the museum (or in this newsletter), but signs of this are everywhere when I look out my west-facing windows or move around the valley.

Drained land made farms. Diked rivers made for reasonable protection against floods, although a month before I moved here, a near-record flood stage on the river threatened the communities along the river. The very shape of the land still shows the efforts of this early transformation.

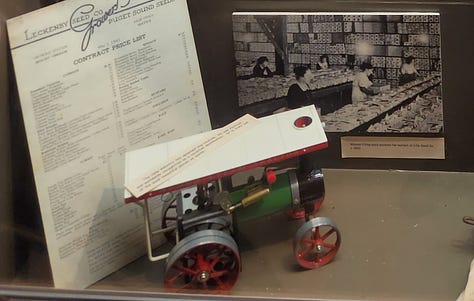

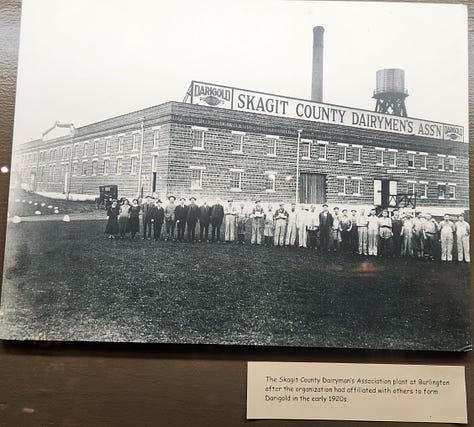

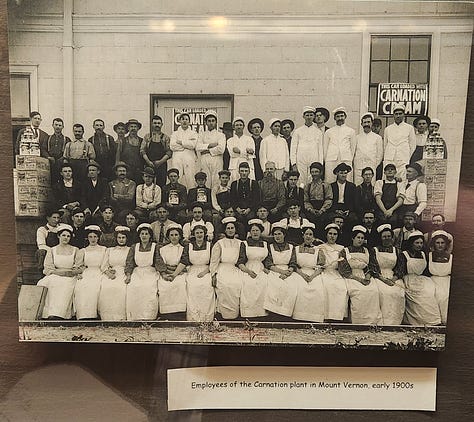

Just before my Interstate exit when I’m driving north, just after crossing the county line, a roadside sign directs visitors to a place for “InFARMation.” It is impossible to miss the agricultural roots and continued presence in Skagit County. What surprised me in the museum was how early signs appeared of large-scale commercial agriculture here–and their scale. The dairy products and seed companies, the large buildings and big workforces (including many women), and eventually the large machines–all of this spoke to investments and connections to larger markets.

This work is equally apparent in the sections on mining and logging, both economic activities that tended to require substantial outside investment since the technologies needed to process ore and timber were significant. Compared with many places in the West, mining was relatively muted here, but timber has been a mainstay. It’s a bit surprising, in fact, that the timber component of the museum remains in the frame of clearing the land more than harvesting board-feet. You could almost forget this is timber country.

Sense of Place

The writer Wallace Stegner claimed that one of his proteges, Wendell Berry, said, “If you don’t know where you are, you don’t know who you are.” Internet sleuths dispute the Berry quotation as original with him. Despite its murky origins, that sentiment certainly reflects Berry’s work through his countless essays, novels, and stories, all growing from his lifelong engagement with Kentucky. In his 1986 essay, “The Sense of Place,” Stegner characterized Berry’s notion:

He is talking about the kind of knowing that involves the senses, the memory, the history of a family or a tribe. He is talking about the knowledge of place that comes from working in it in all weathers, making a living from it, suffering from its catastrophes, loving its mornings or evenings or hot noons, valuing it for the profound investment of labor and feeling that you, your parents and grandparents, your all-but-unknown ancestors have put into it.

Given this characterization, the labor and history I’ve touched on and shown here represents how Skagitonians developed their sense of place at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Certainly many of those who hauled fish out of traps or hacked down huge Douglas firs or diked the flatland outside my window moved in for other labor. But for many, the work represented promise for a stable future.

All of this laboring, all of these changes on the land, seemed permanent and presumed progress. The schools and churches and hospitals–none of these are built without regard for future. No, they are built as a foundation for community. But it didn’t always work out that way.

The Lost Towns of Skagit County

A temporary exhibit on display now explores the lost towns of the county. Here and there, more common than we usually remember, lofty plans went awry.

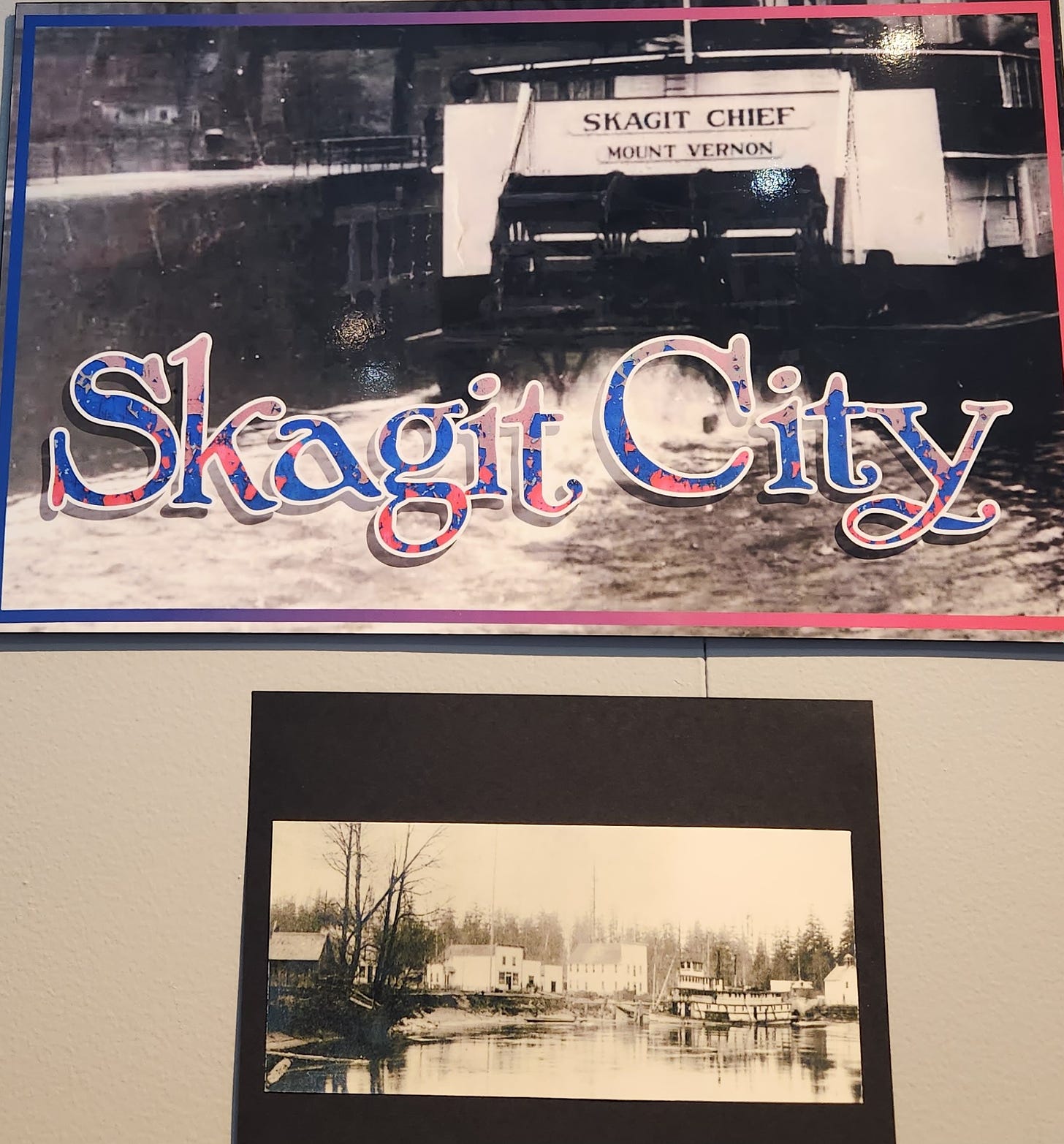

Skagit City, a name that suggests grandeur, had been a ferry crossing and stop for paddle wheeler. Today, a mere schoolhouse-turned-museum remains next to a few farms. No city to be seen, not even a crude crossroads.

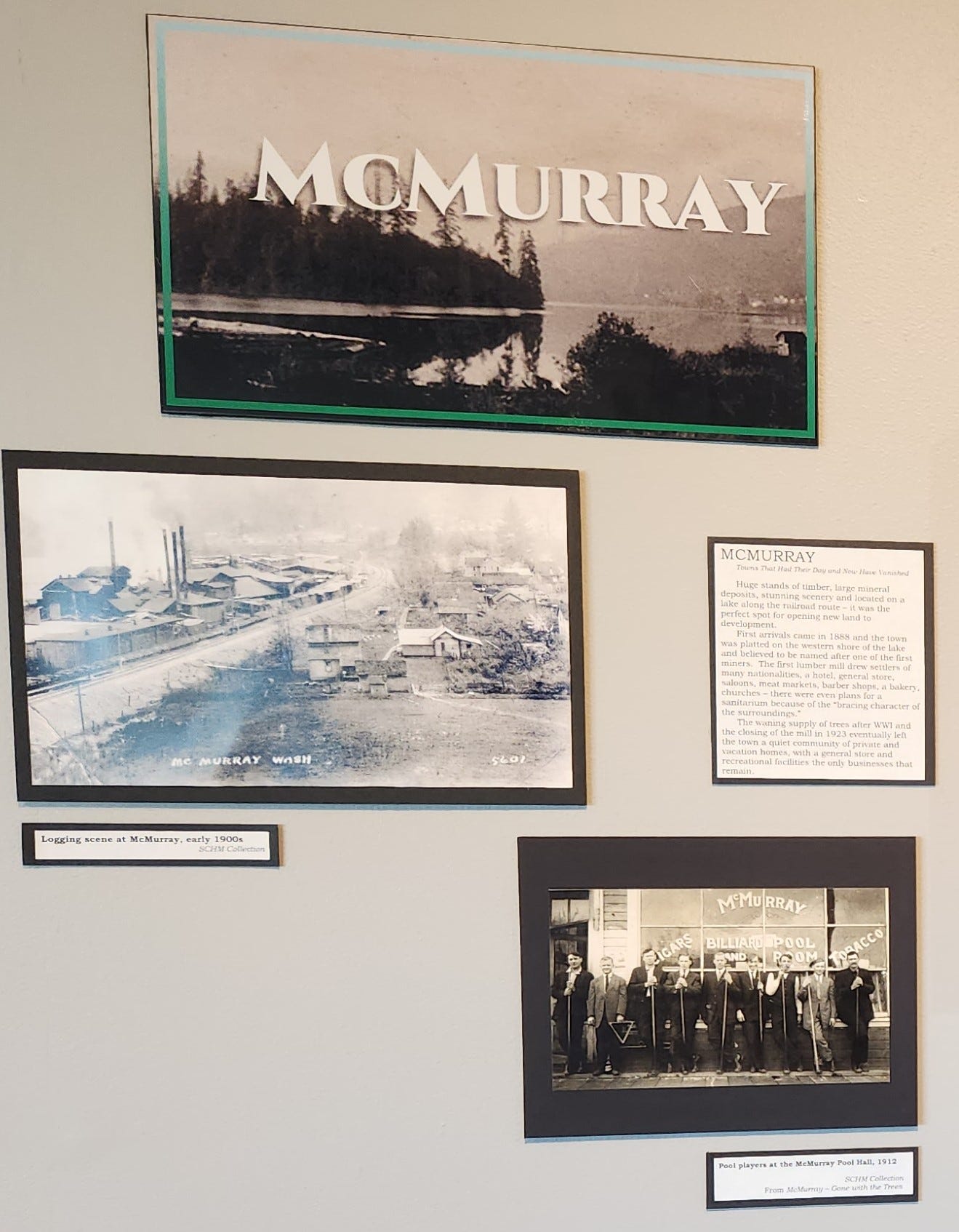

Not far from my house, Lake McMurray draws a few handfuls of seasonal residents and a few more year-round ones. But besides a tiny fire department, there is no sign of a community. A store’s shell still stands, but it looks like it could have been abandoned when President Bush remained in office–the first one. But in decades past, the “lost towns” exhibit shows me, McMurray boasted pool halls and timber mills, something hard to envision during the two-minute drive through the community today when the speed limit temporarily slows from 50 to 25 on the state highway through it.

In the long run, much of history is ephemeral. A church that promised eternal salvation is reclaimed by the elements. A community with streets and a post office and a school is swallowed by a forest. The labor meant to be progress is forgotten, dismissed, or reversed.

What happens to that sense of place forged in transformation?

Post-script: Return

On the drive back from the museum, I stopped by the first place in this new home county that left an impression on me. It’s a small, state-managed wildlife area. Here, on clear days, I can see the Cascade Range and the Olympic Mountains. They are often stunning frames in this part of the world. But the place is special because of the birds.

The first month I lived here, I visited this spot and was met with a flock of small birds–dunlins I later learned–flying together in a mass that made the air shimmer seemingly like magic. From this spot, I heard snow geese chanting and saw them fly with impressive acrobatics. These birds, you can imagine, have been coming here forever, part of the pulse of the universe.

Not exactly.

The posted sign tells me the land here was changed to encourage these birds and promote a more natural habitat. They breached a dike. I wonder about those settlers whose aim was to solidify this place, to make it able to grow things predictably, to hold the bay and sloughs back. What would they think about destroying the dikes and welcoming the ducks?

Closing Words

I have several pieces I’m working on related to this local landscape, but nothing to share yet. Hang out here long enough, and I’ll share them when they are ready.

Last summer, I presented an online lecture about changes to the American landscape for the Idaho Humanities Council. It’s an overview that includes some of the context described here. It slipped through the cracks a bit, but it is available now on YouTube: “The American Landscape: An Introduction through Four Laws, Two Places, and Two People.”

As always, you can find my books and books where some of my work is included at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next week

Next week, I’ll be sharing a bit about the writer and conservationist Bernard DeVoto. Until then, thank you for reading and please consider sharing Taking Bearings.

Well done and very interesting! I enjoyed the read!

You ask "I wonder about those settlers whose aim was to solidify this place, to make it able to grow things predictably, to hold the bay and sloughs back. What would they think about destroying the dikes and welcoming the ducks?" No doubt they would be appalled, dumbfounded and astonished. But they lived in a time when what we call 'natural resources' were assumed to be infinite. Someone would need to explain to them that those trees and wetlands turned out not to be infinite, and that (luckily) we stopped the cutting and diking and draining, then the paving, before it was all gone, and now we've even realized that we went farther than we should have and need to step back and allow the natural world to reclaim some of its original territory -- for our own good!