Before I start this week’s newsletter, please allow me to make an appeal and an offer.

August will mark two years of Taking Bearings, two years of weekly thoughts and lessons about place, history, and writing. I am hoping to increase subscribers and would be grateful if you shared this newsletter with a friend or family member you think would enjoy it. I’ve turned on a referral program. After four referrals, you will be comped free access to paid content for a month (and the rewards increase with more referrals).

I’m also asking that current free subscribers consider upgrading to the paid option. To celebrate the pending two-year anniversary, throughout July (only ONE more week) I am offering a discounted subscription rate.

Thank you for your consideration. ~Adam

Whew! The past month has felt like a decade. I don’t intend for Taking Bearings to be a place for up-to-date commentary on American politics. Still, sometimes the political world sparks ideas.

For The Wild Card this week, I will meander through one of those ideas. Read on!

Comparative Politics

I’m not obsessed with politics, but I pay closer attention than most of the general public. And as a historian, I have a stronger command of past politics than is normal. Also, perhaps because of my accumulating decades, I compare the current political context with earlier ones.

When I start thinking about earlier politics, I think about a concept from fisheries biology. (Don’t you?) More on that in a moment.

Early Political Memories

I did not grow up in an overtly political household. My parents always voted, and a local newspaper and TV news were common presences in our home. But we didn’t talk about issues. To this day, I don’t know who my parents voted for in any election (except maybe the last one). That family history means my early political memories are not thick.

I recall seeing Jimmy Carter on television with — at least in my memory — thick blue or gray curtains behind him. He stood at a podium, looking serious and speaking in an odd cadence. (I assume this speech was connected to hostages in Iran.)

The next memory may have been the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan. This occurred on the first day of spring break when I was in 2nd grade. I remember it in part because my teacher required us to keep a journal during the week. (Thank you, Mrs. Ellis!) The journal, I think, sits in a box in my garage, and if I dug it out, I would see something like, “I watched the Reagan thing on TV” for my Monday entry. A “Good” or something similar angled in the margin.

Hostages and an assassination attempt are fairly heavy first political memories, but I certainly felt no trauma. The people on television seemed dignified, even those Secret Service personnel scrambling to protect the president. The fact that my parents allowed me to watch endless replays of the assassination attempt suggests that they were not worried about me being exposed to anything that would be too difficult — or embarrassing — to explain.

Today’s children and parents live in a different world.

Shifting Baseline Syndrome

That brings me to fisheries biologist Daniel Pauly.

In 1995, Pauly published a short — one page — paper in the journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution called “Anecdotes and the Shifting Baseline Syndrome of Fisheries.” His interest was ocean fisheries and their steady decline. Fisheries scientists had been tasked by governments to help inform management decisions, including figuring out stocks of fish available to be harvested. A problem in this work was the shifting baseline syndrome. Pauly explained:

Essentially, this syndrome has arisen because each generation of fisheries scientists accepts as a baseline the stock size and species composition that occurred at the beginning of their careers, and uses this to evaluate changes. When the next generation starts its career, the stocks have further declined, but it is the stocks at that time that serve as a new baseline. The result obviously is a gradual shift of the baseline, a gradual accommodation of the creeping disappearance of resource species, and inappropriate reference points for evaluating economic losses resulting from overfishing, or for identifying targets for rehabilitation measures.

Pauly has elaborated on the idea over his career, including a TED Talk that has been viewed hundreds of thousands of times. Other people had toyed with similar ideas before and others have elaborated on it since Pauly first tentatively described it.

Pauly pointed out several historical anecdotes concerning earlier fisheries that should help contemporary fisheries scientists revise their assumptions about earlier fish stocks. History would help their assessments arrive at more accurate estimates to inform management and rehabilitation efforts.

One reason the idea appeals to me is its explicit acknowledgement that history is valuable. But the other reason is the concept itself as a warning not only of the problem of judgment without incorporating history but also a reminder of the gradual erosions in our world.

History as (Partial) Antidote

We inherit the world of previous generations and bequeath the world to a new generation. In neither nature nor politics is this looking great in 2024. One of my greatest fears is normalizing all of this.

Young people preparing to vote for the first time in 2024 came of age during one of the most partisan and least productive political moments in American history. One consequence of this is disinterest. (I recommend reading or listening to this recent story about what one teacher is doing to try to engage her students, who are disengaged.) Lately, there have been few big bipartisan successes — by this I mean large bipartisan majorities, not successful examples like the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law that garnered critical, if relatively small, Republican support. By contrast, someone born in 1960 would have come of age seeing major laws passed with overwhelming bipartisan majorities.

I write mostly about environmental themes, and in that sense Pauly’s shifting baseline syndrome and the gradual acceptance of an impoverished environment disturbs me deeply. For example, more than one-quarter of North American birds have disappeared in my lifetime — and things were not in great shape to start with half a century ago. Other examples like this exist.

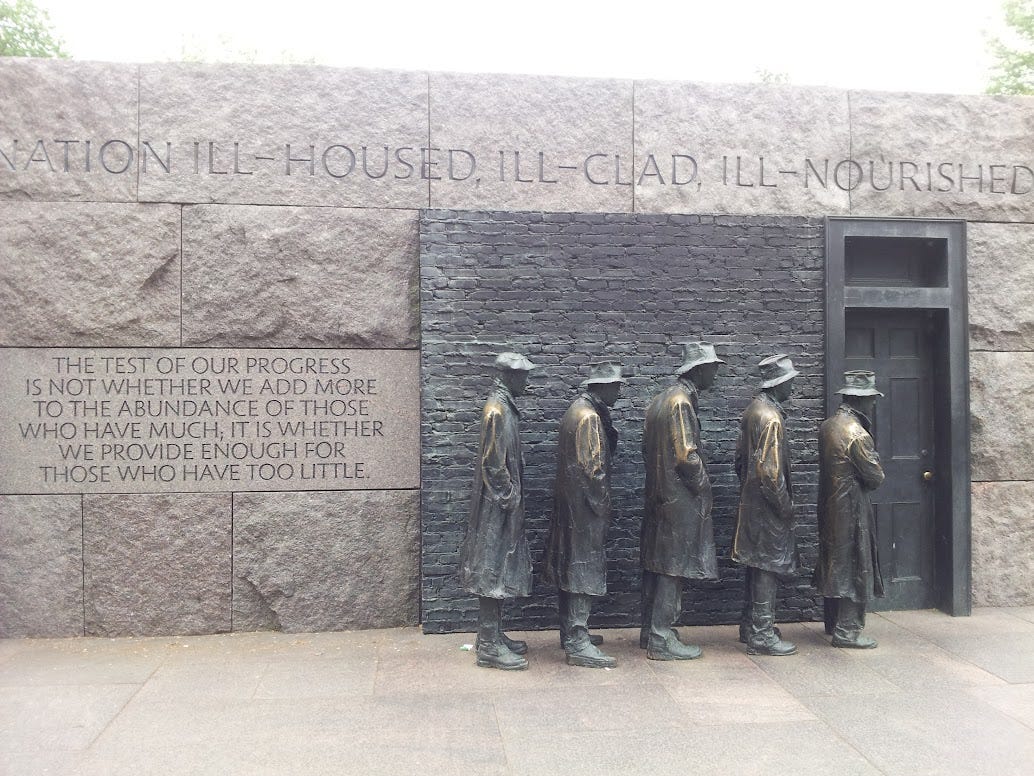

But the political shifting baseline is a pernicious plague, too. The lack of more significant legislation is one measure of the declining political system and the increased polarization and gridlock leaving problems unsolved and people unrepresented.

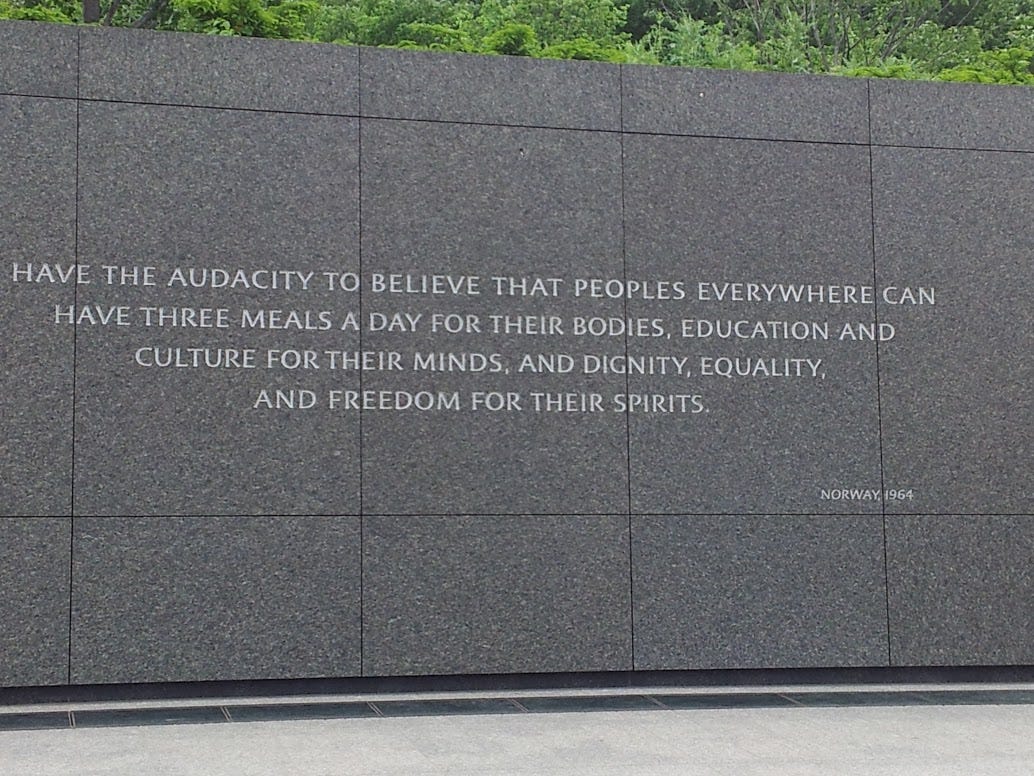

One antidote to stopping this deterioration is to recognize it and recognize that it does not have to be that way and hasn’t always been. That means knowing history better, looking at it squarely. That knowledge can empower a public to make wiser decisions and demand better. A society that devalues history is left adrift, like a biologist trying to understand a system but who only looks over the course of their lifetime. Take a wider view; create a better world.

Closing Words

Relevant Reruns

This old newsletter looked at an E.B. White essay during a presidential election year and feels somewhat relevant. I wrote a column once about a day in 1968 when President Johnson signed several important conservation laws, suggesting a time when polarization was not such a powerful force. You can read it here.

New Writing

I am working, but I have nothing new to share.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

Back to The Classroom next week. Stay tuned!

Such a helpful way to think about our assumptions of what is the norm. Thank you. It's flexible, also. I've been reading parents and teachers talking about their kids' assumptions that nothing ever gets better environmentally, because smog reductions, and ozone hole regeneration, and Great Lakes cleanups happened before their time. Learning that the baseline has sometimes shifted in a good direction can give us hope.