This week is at The Wild Card in my cycle of topics. Over the last three weeks, I posted a series of related newsletters. It started with the National Elk Refuge in Jackson Hole, Wyoming; followed by the Murie Ranch from the same locale; and wrapped up with some reflections of Mardy Murie’s book, Two in the Far North. I’m extending this slightly this week with short portraits of mid-20th-century conservationists.

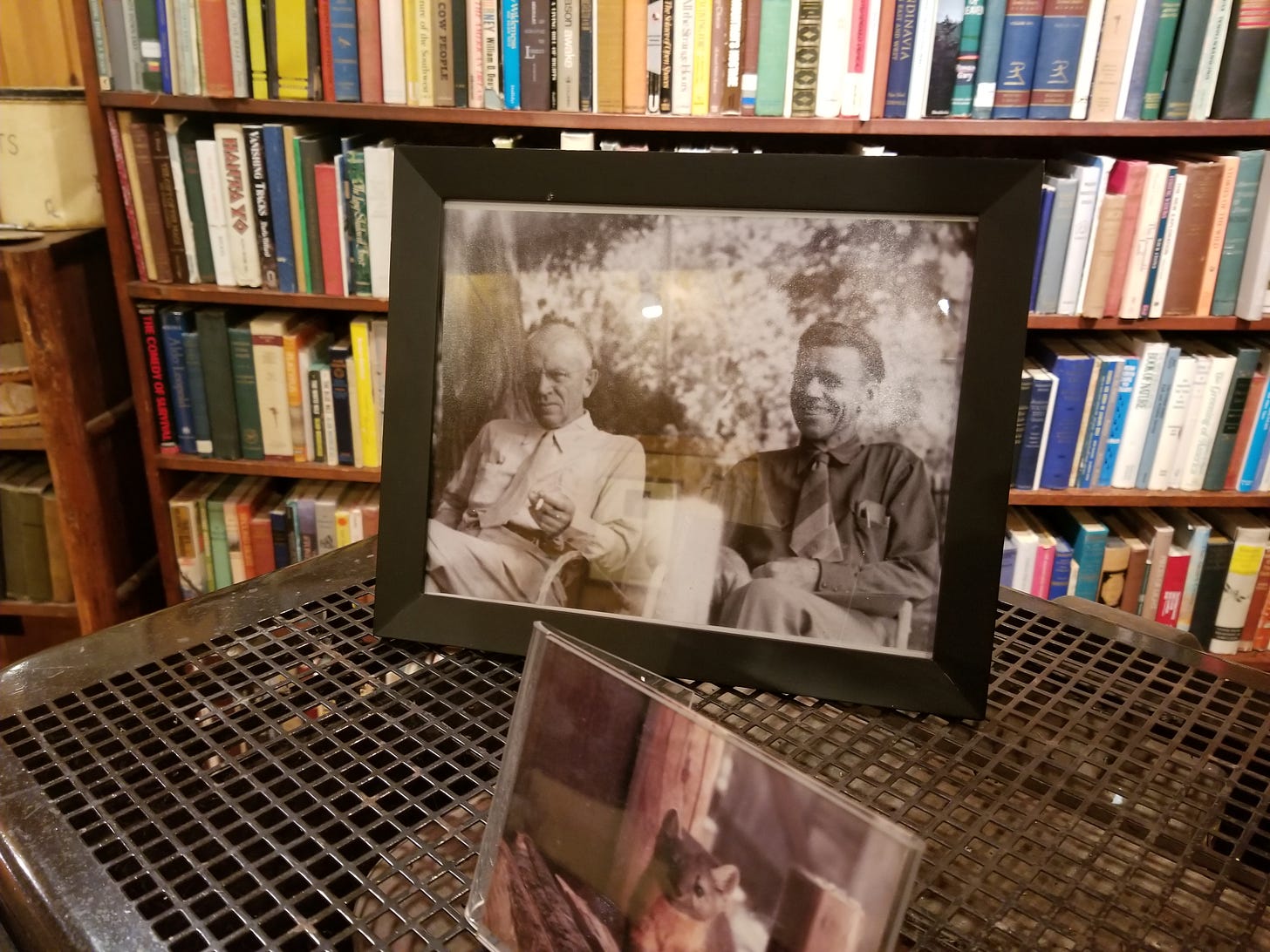

In searching for photos to use last week, I saw one of my favorites (of Olaus Murie and Aldo Leopold) that I had snapped when visiting the Murie Ranch. It got me thinking about how powerful images can be, something that I don’t often consider deeply enough. I started collecting a few images that often stick in my mind from the period where I’ve focused much of my historical research, 1930s-1960s. It didn’t take long to realize they illustrated several avenues toward conservation activism that might reveal something interesting about the moment. Read on!

Bob Marshall and His Pack

Most conservationists spend time outdoors. Their activities can vary from hunting and fishing to camping and birdwatching or even river rafting. Conservationist ranks are filled with hikers, and few developed a hiking reputation as impressive as Bob Marshall (1901-1939). Walking through forests and around mountains gives you a distinct view of the world that sometimes leads to activism.

Marshall was one of The Wilderness Society’s founders and its main benefactor. He worked as a forester for the federal government (both in the US Forest Service and the Bureau of Indian Affairs), becoming a specialist in recreation and an advocate for undeveloped lands. Marshall’s reputation for long hikes is somewhat legendary. Daily hikes of 20, 30, even 40 miles were common.

In the Northwest, Marshall is famous as an advocate for the rugged wilderness in the North Cascades, part of which became North Cascades National Park and some of which is protected in Glacier Peak Wilderness. A story also circulates in the region about how he was in Chelan country and needed to be in Seattle for a meeting. Instead of following roads or railroads, he simply hiked over the Cascade Range. (For those of you who aren’t local, take a look at a map and see where Lake Chelan is compared with Seattle!)

I used this image of Marshall in my very first newsletter (and it elicited comments from some readers), because it is embodies is hiking reputation so well. The size of the pack hints at what his backcountry jaunts might have entailed. Although Marshall thought seriously about wilderness, including its role in preserving freedom, he came to the work on foot.

Olaus Murie and Aldo Leopold: Wild Lives

This image is the one that inspired this week’s newsletter. Olaus Murie (1889-1963) and Aldo Leopold (1887-1948) worked together with The Wilderness Society and contributed to the organization’s work on wilderness preservation, philosophically and politically. What especially united them, however, was their love of wildlife. Murie was the leading expert on elk; Leopold wrote the first game management textbook in the nation. Loving wild animals meant loving wild places; you can’t have one without the other.

Animals often invite people into conservation, because they help us engage a world beyond humans. Conservationists who came of age early in the 20th century – like Leopold and Murie – faced dire wildlife collapses, especially of large mammals. So concern about elk or predator-prey relationships pushed people like Murie and Leopold to use their scientific training, combined with their conservation sensibilities, to advocate for stronger protections for wildlands. (Their contributions probably merit some more discussion in this newsletter at a later date, although if you search, you’ll see these individuals appear here and there already.)

As readers of this newsletter in the past few weeks know, I find the Muries fascinating. And my interest in Leopold goes back to my undergraduate environmental history course where I devoted my term paper to his ideas. So seeing them together – and especially with Murie’s huge grin – stands out. One source (that I cannot confirm) suggests that this photo was taken at a Wildlife Society meeting, which certainly would be appropriate. If hiking got Marshall to think deeply about the wild, big animals pushed Murie and Leopold.

William O. Douglas and Political Power

Although every major conservationist spent hours and hours out of doors, few spent hours and hours in corridors of political power. William O. Douglas (1898-1980) was the exception. Arguably, no one who has served high in American government participated more prominently in conservation politics. Douglas grew up hiking in the Cascades near his home in Yakima and enjoyed climbing much like Bob Marshall. But he also had a full-time job as a US Supreme Court Justice from 1939 to 1975.

Douglas launched his conservation protest career in 1954 when he led a hike along the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal to criticize plans to build a parkway alongside it. When the Washington Post editorialized in favor of the road, Douglas wrote to the paper and encouraged the editors to walk along the canal with him, for if they did that, they would not support ruining it with a road and traffic. It worked.

In spring 1954, a public hike of nearly 200 miles was staged with Douglas, the editors, and conservationists (including Olaus Murie). When they arrived in Washington after a little more than a week, the Secretary of the Interior met them, suggesting how the justice galvanized the public on this issue. It took time, but eventually the canal was protected by the National Park Service.

Douglas arrived at conservation through his own hiking and experience in mountains but also as a political figure. This made him distinct in this period (as I and others have argued). This image illustrates clearly how Douglas understood how political conservation operated: gain a popular following and get it in front of governing power.

Rachel Carson and the Science and Art of the Sea

Rachel Carson (1907-1964) helped launch a popular ecology movement with Silent Spring, which warned of the poisoning of nature occurring with the indiscriminate use of DDT. She also was a beautiful writer. But at root, Carson was a scientist of the sea. Carson’s training as a scientist and work as a writer for the US Fish and Wildlife Service gave her unusually useful experiences to develop a conservation career.

If you read her work or biographies Carson, you quickly understand how exploring the natural world drove her ideas and commitment. Silent Spring, as important as it was to Carson and the world, was a bit of a break for her. The rest of her published books focused on the sea. In the mid-20th century, new facts about oceans were being discovered rapidly. Carson was a popular communicator about that new science.

So, whenever I think of Carson, this is the image that comes to mind. A scientist in her preferred element. Also, not a lone individual but with a colleague. The man is Bob Hines, a wildlife artist who worked for the US Fish and Wildlife Service and illustrated Carson’s book The Edge of the Sea. (They grew close enough that he also served as one of her pall bearers.) This image, then, mixes a scientist at work and an artist alongside, something that Carson instinctively understood to be central to conservation of nature and teaching its value to the public.

Images’ Lasting Power

These portraits (the images and short biographies) capture a handful of influential people who shaped Americans’ relationship to conservation at a pivotal time. Their words and deeds matter. But often it is the images that come to mind when their names are uttered.

Closing Words

I’ve mentioned my work on Douglas several times already, as well as the recent references to the Muries. You can find links to that work elsewhere in these newsletters.

I do have a new piece of writing freshly published. It is a short article about agriculture where I currently live and the distinct system of land trading that has developed here and why. It’s fascinating. Take a look here.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

I’ve enjoyed the series of semi-related posts and am planning on trying that again starting next week looking at things related to Pacific Northwest forests. Stay tuned!

As we move in the direction of summer, I’m making a push to increase my subscribers and the engagement with these Taking Bearings newsletters. So if you want to help with that, please press the Like button below or leave a Comment. If you know others who might enjoy this weekly newsletter, please share it with them. And if you are able, consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Thank you for reading.