The teacher appears when the student is ready. This sentiment originates in Buddhist teachings, but it applies more broadly. In this case, the teacher was Barry Lopez, and I was the student by way of an archived 36-year-old letter to a different writer, Stephen Trimble.

Serendipity makes for good stories—and sometimes useful writing advice.

Sabbatical Advice

During the 2019-20 academic year, I took a sabbatical. For my first research trip, I loaded up our campervan, which I called a Mobile Writing Lab, and headed to some university archives, camping in public lands along the way. In campgrounds in the mornings and evenings, I wrote and read productively.

One of the books I carried with me was Barry Lopez’s Horizon, a wide-ranging and beautiful collection of Lopez’s insights. I underlined passages of eloquence. And I starred good advice so that I might see more like Lopez.

For instance:

Over the years, camped with researchers in the field in different situations, I’ve found it helpful to maintain a curious instead of a skeptical frame of mind, at least initially.

Academics quickly don skepticism as a security blanket, a familiar and comfortable garb that can be tried on in any circumstance. We can always be critical, but here was Lopez telling me to be curious to start—a good reminder I wanted to keep with me during the sabbatical and beyond.

Lopez also pointed out that the land itself taught willing students:

A landscape around us, I knew, was the great teacher here. You just had to step into it, with an open mind and an eager heart.

At the start of my new writing project, I found all of this advice useful, perspectives to keep fresh as I launched my research.

Anyone reading Horizon could have access to these tips, but soon I found more private writing advice.

Following Hunches

I stayed in a Forest Service campground in Little Cottonwood Canyon outside Salt Lake City for a few August days while using the archives at the University of Utah. The archival item I most wanted to see proved to be disappointing, not an unfamiliar outcome but a tale for another day.

Researching is about making careful plans and then deviating from them.

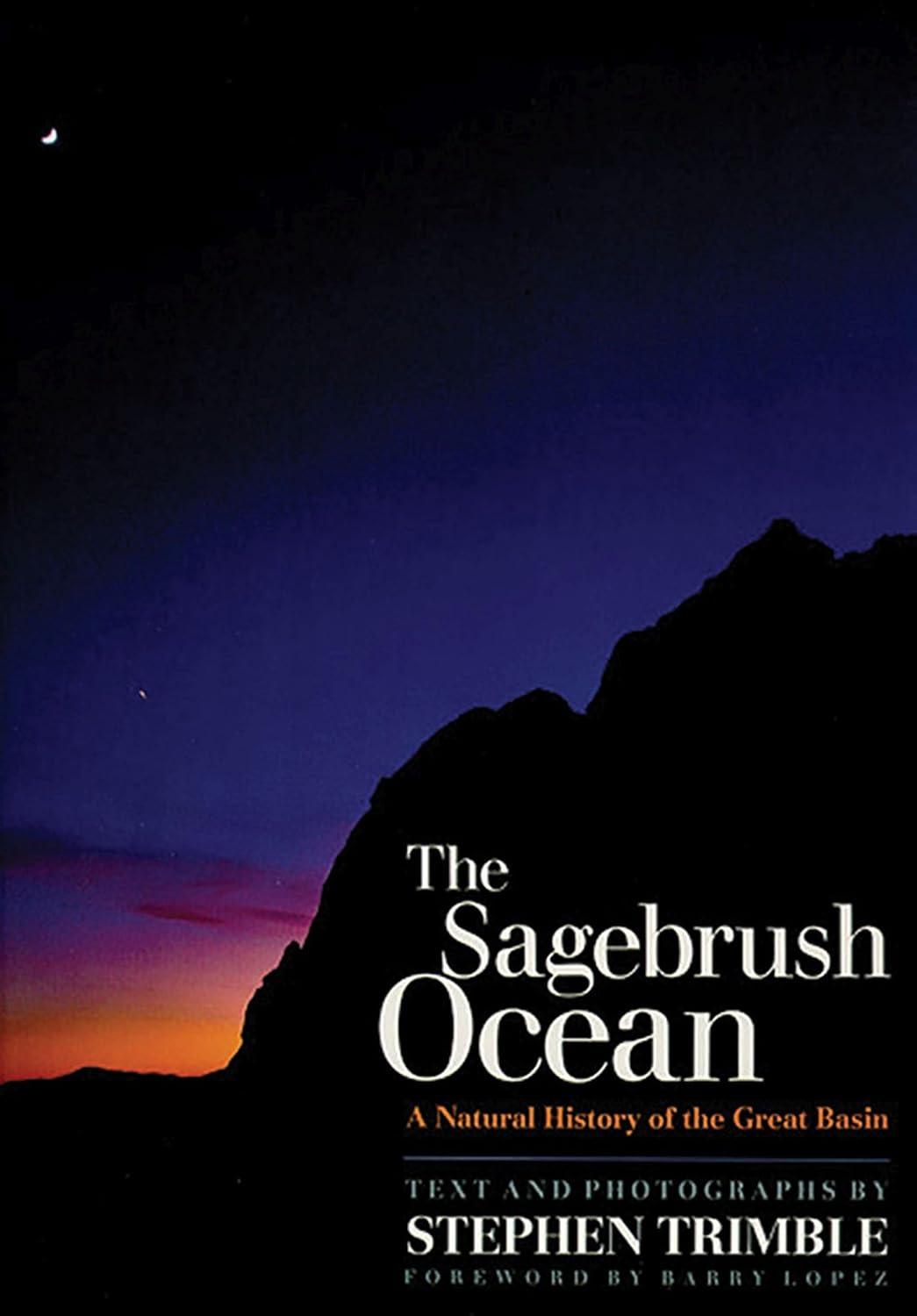

Sagebrush had drawn my interest, and the writer and photographer Stephen Trimble, author of The Sagebrush Ocean, had donated some of his papers to the archives. I was following a notion that they might be useful.

I found chapter drafts. I found pages of title options—notably not The Sagebrush Ocean. I found note fragments. All these pieces helped me see how Trimble conceived of his subject, the Great Basin and its vast sagebrush. All of this material I imagined being relevant to the writing project I had undertaken.

But the very first thing I opened was something else. A folder of correspondence from Barry Lopez looked irresistible. I followed my hunch.

“No Clean First Drafts”

The letters were written when Lopez was completing his magnificent Arctic Dreams (published in 1986) and while Trimble was finishing his beautiful The Sagebrush Ocean (published in 1989). The archives only preserved the letters from Lopez, but context provides clues as to Trimble’s side of the conversation.

Trimble had written about a problem he was facing with technical papers, those written by scientists. The problem in using such work, as Lopez summarized it, was that “their language becomes your language.” And that language is notoriously bad. Lopez quoted the poet Richard Hugo to bolster the point: “In academic writing, clarity runs a poor second to invulnerability.”

Lopez continued sympathetically, “When you are trying to assemble a lot of technical information winnowing out what you want, you naturally fall into the habit of this language because the language acts as a kind of defense against your own ignorance.” This is another sort of security blanket.

When you are beginning to write, you are relatively uninformed. You rely on experts. It is natural to “parrot” them before you’ve understood the technical details yourself and what fits with your own writing.

That’s ok, Lopez says. At the beginning.

“Trying to get the sciencese out too early can disrupt the far more important process of understanding what you are saying,” advised Lopez. Once you understand for yourself, then you can repair your writing.

After all, Lopez reminded him, “There are no clean first drafts, for good reason.”

Being a Gracious Writer

I am not sure what particulars had tripped up Trimble, but I recognized exactly what Lopez was describing from my own writing practices.

When starting with sources, especially complicated ones, I have found it is easy to mimic or summarize sources in their voices. But readers want to hear the writer’s voice. I would also wager that most often readers want that curious voice Lopez described in Horizon, not the critical one.

The familiarity of the problem is what first stood out to me in Lopez’s comment. But his sympathy and graciousness are revealed by the reassurance that it is acceptable, even useful, to draft this way. It is a necessary step on your way, groping toward your understanding and the story you want to tell.

I don’t know Trimble’s reaction, but I know that Lopez made me feel better.

As a parting shot, Lopez revealed something more of his character, because even though his advice was gentle and sympathetic toward an accomplished writer he considered a peer, Lopez still worried. “My unsolicited two cents makes me feel a little sheepish,” wrote Lopez.

It is a common feeling among writers offering advice.