A week from today marks the 50th anniversary of the Endangered Species Act. The ESA sits centrally in many environmental conflicts, and calls to reform it (or gut it) have been persistent for a generation. Yet when President Richard Nixon signed the law in 1973, it represented a popular sentiment. And while perhaps criticisms are warranted about how the law functions, its creation represented an important democratic and ethical extension in environmental politics. A little history of this path-breaking law seems in order for The Classroom this week. Read on!

Beyond Overhunting

The first big concern about extinctions in American history focused on overhunting. The bison and passenger pigeon were object lessons that abundance could be reduced to scarcity (or disappearance). By the mid-20th century, ecologists recognized that habitat destruction led to species decline, too. Solving extinction would have to address both destruction of species and what species relied on. To do that required changing how we think.

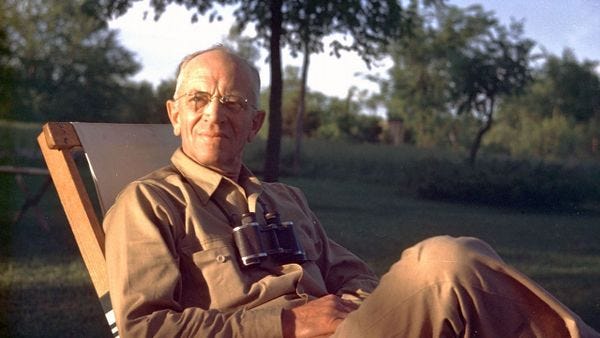

Aldo Leopold, a forester with a gift for words, articulated that new way a thinking, a land ethic. After working professionally in the Forest Service and thinking deeply about land use and wilderness, Leopold came to articulate different set of values to govern how humans should treat the earth. In his classic book A Sand County Almanac (1949), he wrote: “A land ethic of course cannot prevent the alteration, management, and use of these ‘resources,’ but it does affirm their right to continued existence, and, at least in spots, their continued existence in a natural state” (emphasis added). This passage made the case for protecting species and their habitats.

Congress and the public that elected it was not ready to pass legislation yet. But conditions worsened and caused alarm when new chemicals found their way into ecosystems where they affected many species, notably the bald eagle. Rachel Carson chronicled this story in Silent Spring (1962) where she introduced to a broad public the idea that “in nature nothing exists alone.” Carson sparked a mass movement for environmental protection.

Legislation

In the 1960s, Congress passed a couple laws to protect species in 1966 and 1969. They mandated the Secretary of the Interior keep track of a list of endangered species and protect them. These initial efforts proved too weak. Finally, in 1973, Congress passed the ESA, with merely a dozen “No” votes in the House and no objections in the Senate. Section 7 directed the government to stop itself from jeopardizing “the continued existence of such endangered species and threatened species.” (There’s that Leopoldian phrase again . . . continued existence.)

When he signed it, Nixon said, “Nothing is more priceless and more worthy of preservation than the rich array of animal life with which our country has been blessed. It is a many-faceted treasure, of value to scholars, scientists, and nature lovers alike, and it forms a vital part of the heritage we all share as Americans.”

Nixon did not say so explicitly, but the ESA advanced democratic environmental governance. Although the process of getting a species listed as endangered or threatened—and thus gaining extra protections—typically relied on a expert scientific advice, the public could also petition for these protections. And during the debate, public hearings were required.

Extending Democratic Ethics

For most of the 20th century when conservation arose in government, activities were largely controlled by a small group of government officials. Part of the environmental revolution in the 1960s and 1970s cracked open that narrow community to a larger public.

Doing so swiftly moved the ESA into the courts where the potential radicalism of the law became obvious and surprised many of those who voted for it without much thought. In the first major case to reach the Supreme Court, the decision read in part, “The plain intent of Congress in enacting this statute was to halt and reverse the trend toward species extinction, whatever the cost.” Whatever the cost!

In the time that has passed since those heady days, compromises and bureaucratic routines have stifled some of the more transformational potential of the law. And, it turns out, the mechanisms involved have produced mixed results. On the one hand, only 11 species have gone extinct after being listed, and 46 have recovered well enough to be removed from the endangered species list. By some metrics, this could be counted as successful. However, something like 1,700 species remain on the list, arguably because they receive protection too late.

Paved with Good Intentions

In “The Land Ethic,” Leopold wrote,

Conservation is paved with good intentions which prove to be futile, or even dangerous, because they are devoid of critical understanding either of the land, or of economic land-use. I think it is a truism that as the ethical frontier advances from the individual to the community, its intellectual content increases.

The spirit of Leopold here requires understanding of how things work ecologically – and practically—and expanding our vision to incorporate the broadest possible concept of community, something embedded in the ESA even today, 50 years after it became law.

Closing Words

Old Writing

In the past, I have written generally about the Endangered Species Act in my last book. I also explored it in this column in High Country News. Recently for Salish Current, I wrote about efforts to recover the grizzly bear, which explores some of the bureaucratic options involved.

New Writing

Two new stories are out this week. Remember my newsletter about organic agriculture? This story expands that in new, interesting directions. I’ve also been exploring local food systems and food security questions. More will be coming, but here is a first installment. Please check out this work and if the spirit moves you, support local journalism.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Special Offer

A reminder that I’m offering a 20% discount between Thanksgiving and New Years for subscriptions to Taking Bearings. I hope you’ll consider supporting my work and enjoying access to extra features, including a monthly interview with another writer or artist.

Taking Bearings Next Week

The Field Trip is back next week, just in time for holiday travel. Speaking of which, for those who celebrate this time of year, may you enjoy the busy week and may you make good memories.