The first big hurdle was past. We had started!

This is often the case, as Margaret “Mardy” Murie (1902-2003) recognized. We need to start to complete big things. In this case, Murie was focusing on an Alaskan expedition, but it could just as easily represent the critical activism she and Olaus Murie participated in.

Two in the Far North is a memoir of Mardy’s time in and love for Alaska, and I think it is a welcome choice for The Library. In it, she offers portraits of people and place that celebrate life in the wild. Read on!

The Book

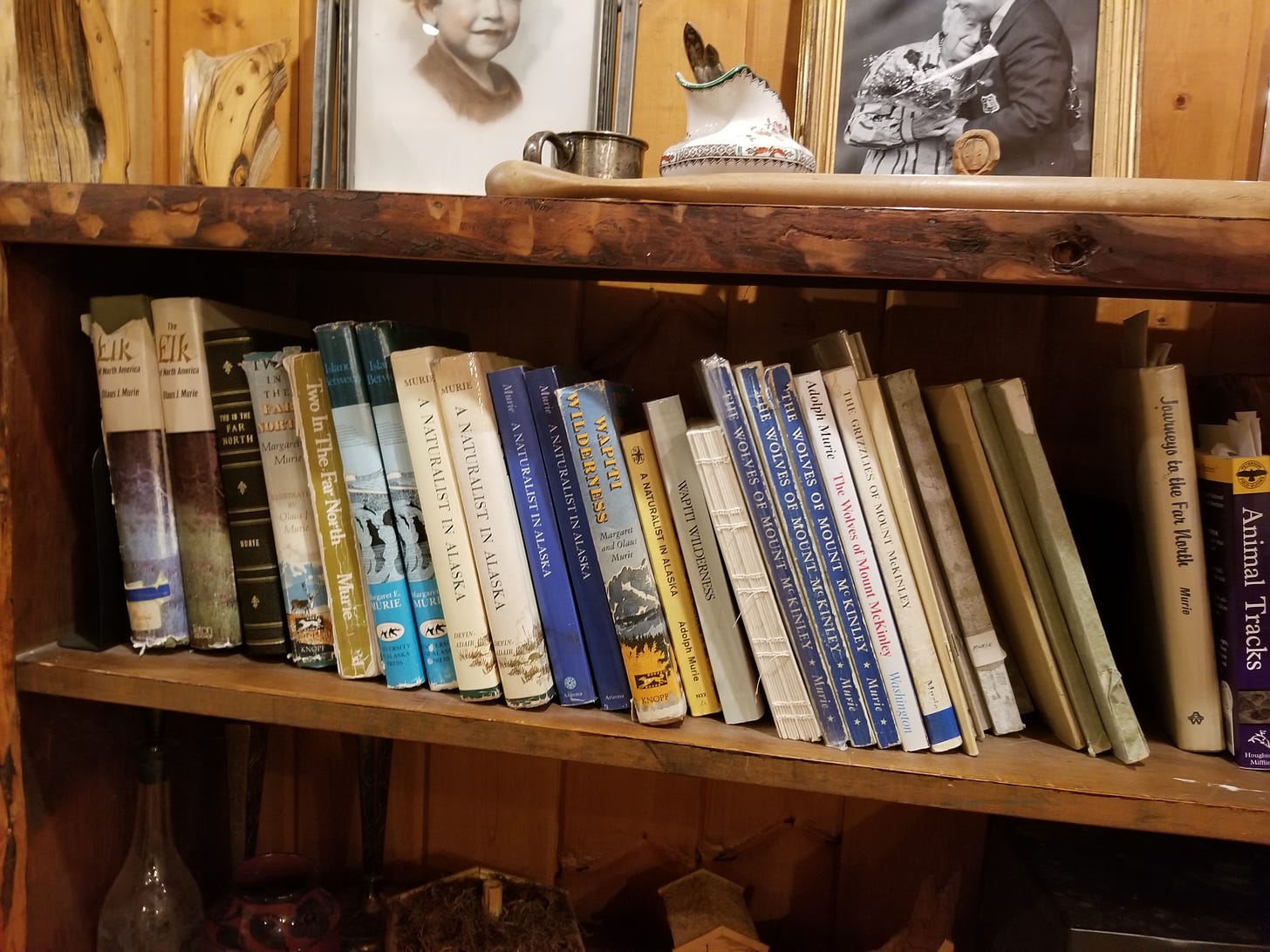

Murie mostly grew up in Fairbanks, and the opening section of the book describes what that life entailed just a couple decades after the gold rush. The next section skips ahead to her early twenties and her marriage to the wildlife biologist Olaus Murie, following their time in the Koyukuk River country. Then, she includes a section on the Old Crow River region. These two sections detail the adventure that travel and field biology entailed in backcountry Alaska in the 1920s. The fourth part is about a summer in 1956 spent further north in the Sheenjek country. A final section and an afterword (called “Afterward”) tell of subsequent trips to Alaska after the initial publication of the book in 1962. These later sections, when the Muries returned, speak to the value of wild spaces than just the adventures of living there.

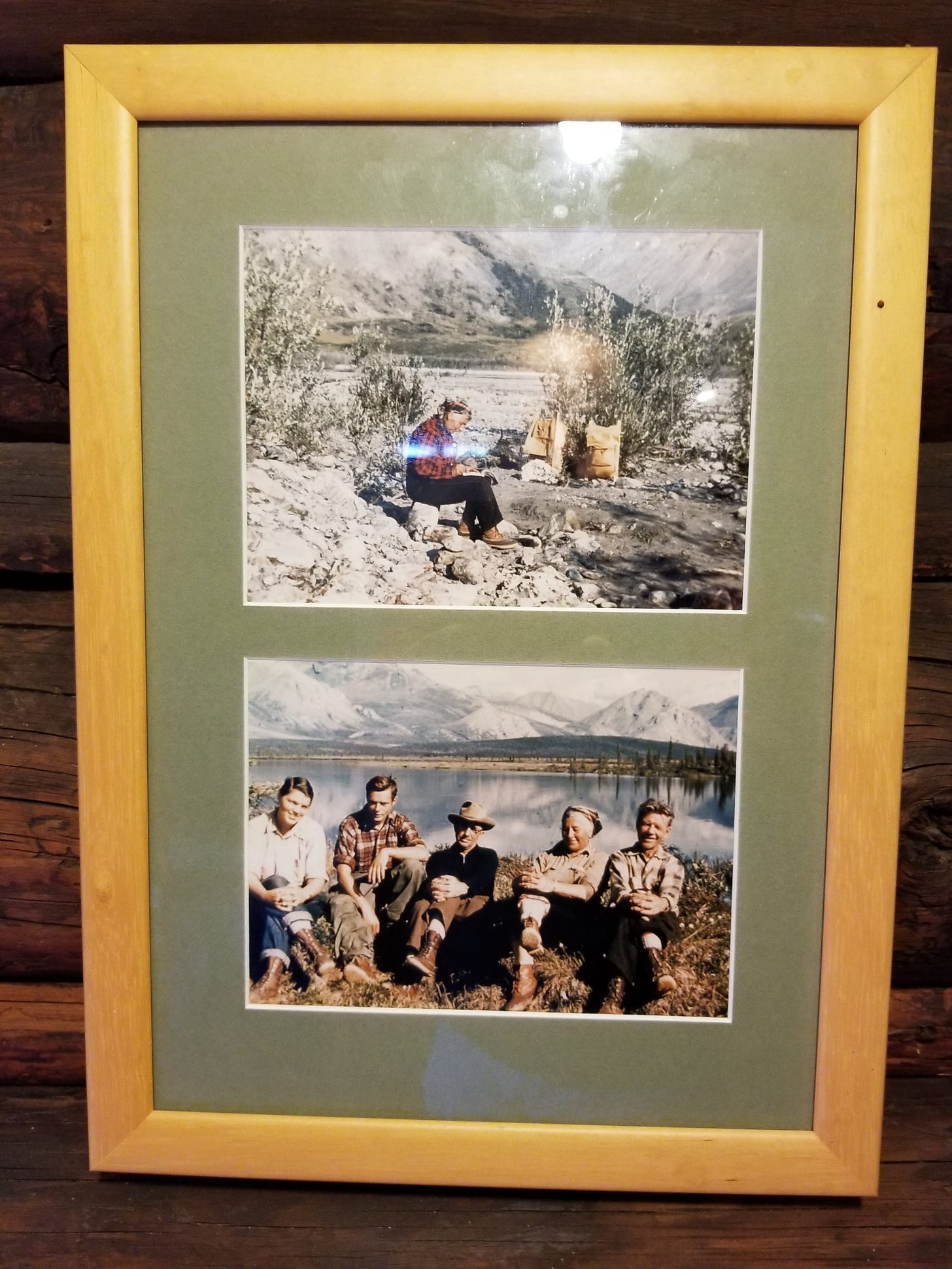

Murie infuses the book with warmth and affection, much as their cabin still feels like an embrace. (After Olaus died, Mardy didn’t think she’d be able to return to it, but she noted, “It was almost as though this loved log house put its arms around me.”) To read Two in the Far North is to be in good company and to revisit an earlier time in conservation history with a consummate guide. Below are couple themes I found revealing.

Integrity & Partnership

When Mardy first met Olaus, he shared a story about a scientist who falsified a record. When the fraud was discovered, the scientist was never heard from again. Olaus told her, “You see, all a scientist has is his integrity.” This comment settled deep within her and came back at times. One such moment occupies an important point in the book.

After marrying, the Muries headed up the Koyukuk River. Mardy assisted Olaus who was completing a life history study of caribou. For weeks, they were constant companions. Then, Olaus headed out for a couple days, leaving Mardy behind in camp. “I have never minded being alone in the wilderness; it has always seemed a friendly place,” she said. But time took its toll, and she wondered why Olaus was slow in returning. When he finally arrived at camp, he found her sobbing.

Mardy asked him, “Didn’t you know I’d be worried?” He replied, “Things take longer than you think, you know.” That simple.

As Mardy described it, with nearly four decades of reflection, she knew she had to change her thinking. “The work came first. ‘All a scientist has is his integrity.’” According to her, “I came to terms with being a scientist’s wife.”

Such a sentiment smacks today of accommodating sexist norms. Mardy didn’t see it like that. Neither did Olaus. At least in available accounts. They were collaborators, partners in all ways. Four years after Two in the Far North was published, they published a book together, Wapiti Wilderness that offers even stronger evidence of how entwined was their lives and work.

The edition of Two in the Far North I own is a 35th anniversary edition with a Foreword by Terry Tempest Williams, who knew Mardy. Tempest Williams noted that Mardy “has exhibited – through her marriage, her children, her writing, and her activism – that a whole life is possible.” Further, she commented, that, “We can also remember that all good biology begins in partnership. The partnership of Olaus and Margaret Murie was a partnership with nature – pure and impassioned.” These themes rise off the pages frequently.

Ideas & Values

Throughout the book, Murie expresses nature as autonomous. After a long, difficult day traveling by dogsled, she captured this nicely:

The sky was overcast, so it was a quiet black and white and gray symphony – no wind, a still, workaday kind of world, yet even through fatigue and the ache of bruises, I felt its beauty. It was the North as it so often is, gray, quiet, self-sufficient, and aloof; you couldn’t help feeling the strength of the land in it.

I like this passage particularly because it is not monumental, as so many expressions of the nature canon are. Even workaday nature in Murie’s mind rises and transcends.

One summer, the Muries took their baby to the Old Crow River to band geese. As they got started up the Yukon River, the first stage of many, Murie captured the independent sentiment again:

The river seemed to tolerate us kindly. We attribute personalities to all things of nature; I suppose we can’t help it, being the self-centered creatures that we are. The Yukon has been both devil and angel to the various people who have traveled upon it. To us it seemed a kindly yet reserved host – a giant of enormous power disposed to accept us and give us safe passage this time. We were interlopers of course. This world belonged to the river, to the birches and spruces on the cut banks, to the terns and plovers on the bars, to the black bears who sometimes ambled along the tops of the banks, to the unique black ground squirrels that scurried through driftwood piles behind the beaches. [emphasis added]

I love the idea of the world belonging to the river. It’s a way of decentering humans, of locating in a landscape the animating force. (This can, of course, be taken to misanthropic extremes.)

Later, in the Sheenjek, Murie sounds a similar tone:

The environment is not tailored to man; it is itself, for itself. All its creatures fit in. They know how, from ages past. Man fits in or fights it. Fitting in, living in it, carries challenge, exhilaration, and peace.

This passage emphasizes the options for people: fit or fight.

Murie touches on this increasingly in the later stages of the book, because she became a central figure in the fight to protect wilderness in Alaska and elsewhere. She worried about machines, a stand-in for technology writ large. She recognized technology’s value depended on humans.

In every phase of life, from the cold war to building new towns, machines will be destroyers or benefactors according to the way in which they are used by man.

With reverence toward life, she continued, people could protect places from what she called the “idolatry of the machine.” In one of her “afterward” chapters, Murie fretted that “we have lost control over the beings we have created.” (This certainly resonates with today’s concerns about AI.)

Still Hopeful

Despite those concerns, Mardy Murie, who Terry Tempest Williams dubbed “our spiritual grandmother,” retained hope. Preserving the natural world for her great-grandchildren was her life’s work. She still believed that those generations “may someday journey to Sheenjek and still find the gray wolf trotting across the ice of Lobo Lake.”

It seems to me we owe it to Mardy to work to continue this work.

Closing Words

For a brief time, I became professionally focused on the Arctic, especially scientific exploration. I thought I might write a book, but instead I only produced this single article. Its context is slightly earlier than the Muries’ earliest forays into wildlife study in Alaska. In addition, I take up Alaska’s role in conservation politics in the 1970s in Making America’s Public Lands (found through the link below).

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

My last three newsletters have had related themes, and I think I’ve devised a way to partly continue the series next week in The Wild Card. Stay tuned!

As we move in the direction of summer, I’m making a push to increase my subscribers and the engagement with these Taking Bearings newsletters. (I hit one milestone I had my eye on — thank you new subscribers! — but have more ahead.) So if you want to help with that, please press the Like button below or leave a Comment. If you know others who might enjoy this weekly newsletter, please share it with them. And if you are able, consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Thank you for reading.