Most of my newsletters over the last month have focused on forests, as I’ve been anticipating my writing residency at H. J. Andrews Experimental Forest. Now that I’m here and my newsletter cycle is back to The Classroom, I figured I should write a bit about this place’s history.

In this short space, I cannot explore everything of interest historically (please forgive me!), so I’m offering just an overview that highlights a couple significant trends. Read on!

Context and Origins

The Andrews (what everyone calls it) is on the Willamette National Forest and is administered in partnership with the national forest, Oregon State University, and the Forest Service’s Pacific Northwest Research Station.

The U.S. Forest Service has long been charged with not only managing public forests but also with researching them.

In the earliest years of its research program, the agenda focused on instrumental values. That is, how could the agency manage resources in a way that promoted use of resources to benefit human enterprises. Most of the time that meant things like:

how can the rangeland yield more forage for livestock?

how can the watershed yield more water for irrigation?

how can the forest yield more timber?

That last question, more or less, guided the Forest Service in mid-20th century. With the end of the Depression and World War II, a building boom was anticipated, and private forestlands had been cut to a large degree. The Forest Service had mostly been a custodial agency, holding on to forests. But the postwar era would see it open its forests to logging.

In 1948, the Forest Service created the Blue River Experimental Forest in Oregon’s Central Cascades, a complete watershed for Lookout Creek. H. J. Andrews had been the Regional Forester based in Portland before moving on to Washington, DC. He died in a car accident and the experimental forest that he helped create was renamed to honor him in 1953.

Among the most important questions asked in the early years focused on how logging affected forests broadly speaking. An article of faith among foresters in this period was that old forests were decadent, which was wasteful. Instead, they needed to be replaced with faster-growing, younger trees. Experiments on the Andrews tested these ideas (and many more).

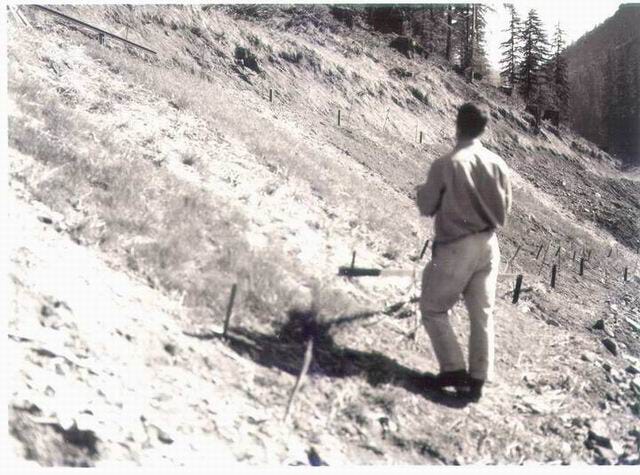

Through the 1950s and into the 1970s, researchers established experimental watersheds to monitor activity. And 25% of the forest was cut, often in clearcuts but occasionally other strategies were tried. Scientists put up their instruments, recording and counting things as they tried to understand forests. This means the Andrews has developed a long-term set of data and observations useful to subsequent studies.

Integrative Work

Their efforts kept accumulating. Meanwhile, regional trends imposed opportunities for making forestry research socially relevant, as well as politically fraught.

The postwar logging boom devastated Northwest forests. This helped keep mills chugging and loggers happy. But costs accumulated and other values ascended.

By the 1970s, popular movements to protect “the environment” succeeded in getting Congress to pass many laws that protected species and forced the Forest Service to consider values other than board feet. Science produced at the Andrews influenced and interacted with these changes.

The last time I wrote The Classroom for this newsletter, I focused on the northern spotted owl and how efforts to protect it changed the Forest Service. Some of that research occurred here on the Andrews.

To vastly oversimplify, the researchers here began study from an ecosystems science perspective. That meant integrative, multidisciplinary, collaborative science. Much of what scientists found once they started looking showed that clearcutting – the favored method of the postwar timber industry – weakened forest health overall and caused many specific problems, such as endangering species. The work done on the Andrews helped focus attention on disturbance ecology with the recognition that landscapes face many disturbances over long periods – such as fires, floods, roads, and logging – caused by humans and forces beyond humans. By researching how the forest “worked,” scientists learned what failed the forest, too.

Long-term Thinking

Thinking long term became a hallmark of work on the Andrews. In part, that focus was prompted by national and international efforts in science to monitor ecologies over long eras. In 1980, the Andrews earned its first National Science Foundation Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) grant. It is one of several sites in a network focused on this sort of long-term study.

One experiment I’ve been able to see demonstrates this atypical focus. With others, including the investigator who started the experiment almost 40 years ago, I visited a decomposition study site. In the mid-1980s, researchers laid out logs and have been monitoring them as they decay into the forest floor. This is not that unusual as far as scientific experiments go. What is unusual is the experiment is designed to go on for 200 years. This is slightly longer than a typical funding cycle or graduate research agenda designed to produce an MS or PhD!

Even more special – and the reason I’m here – is that innovative thinkers at and around the Andrews determined that artists and humanists needed to be involved in a similar long-term thinking project. Starting two decades ago, writers and artists and philosophers (and now a historian) have been brought here to reflect on and be inspired by the forest and the discoveries that can be made here. As scientists gather hydrological or dendrological data, humanists produce cultural data.

Discovery, after all, comes in many forms.

Postscript

In 2020, a huge fire ripped through the river valley just downstream. Parts of the Andrews were hit, a small portion of the nearly 175,000 acres that burned up, including some 400 homes. This was a more violent and tragic disturbance than is typical. Yet, the old-growth Douglas fir forest that blanketed much of western Oregon and Washington probably has its origin in a similar burn (although without the loss of home structures in the same way). It provides yet another opportunity to see how nature works and respond to the social pressures and questions. In this way, it’s just another day at the office.

Resources

The Andrews Forest website includes a great deal of information, including many scientific studies. There is a brief program history, as well. A very useful infographic that charts out research trends is well worth exploring; click here and zoom (Highly Recommended!). Writers and historians have used Andrews for parts of their books and articles. A recent history by William G. Robbins, A Place for Inquiry, A Place for Wonder: The Andrews Forest is a good way to get an overview.

Final Words

As I’ve stated before, much of my writing has focused on national forests. My Master’s thesis was a history of one national forest (that I covered in this article and this one). My most recent book is a history of public lands and provides all the context for the Andrews story. I look forward to writing more about this place in the coming weeks, months, and years and will alert you when material appears. If you are interested in following along, I’ve been posting short, daily reflections of my time here in Substack’s Notes area.

Unrelated, this week my latest story about agriculture appeared. You can check it out here.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

Next week, The Field Trip appears in my rotation. Pretty much every day is a field trip on the Andrews, so I’ll have many things to choose from. Stay tuned!

As we move in the direction of summer, I’m making a push to increase my subscribers and the engagement with these Taking Bearings newsletters. So if you want to help with that, please press the Like button below or leave a Comment. If you know others who might enjoy this weekly newsletter, please share it with them. And if you are able, consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Thank you for reading.

👍👍🌳🌳