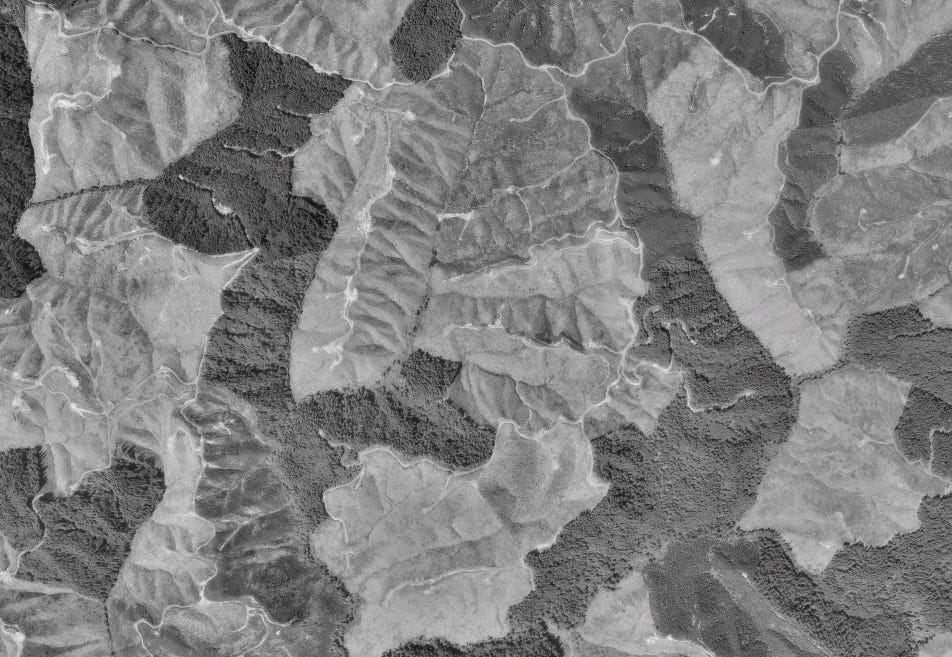

In southwestern Washington, in the 1980s, lay a “ravaged land.” Clearcutting had devastated the Willapa Hills. Accelerating decades of short-term thinking produced a compromised timberland and weakened economy. Disintegrating natural and human communities were scattered across this once-grand forest. Amid the stumps lived a keen observer, Robert Michael Pyle, who wrote a book that’s become a classic: Wintergreen: Rambles in a Ravaged Land, first published in 1986 and then republished in 2001. It remains worthy of attention. Read on!

“All this is the rain world.”

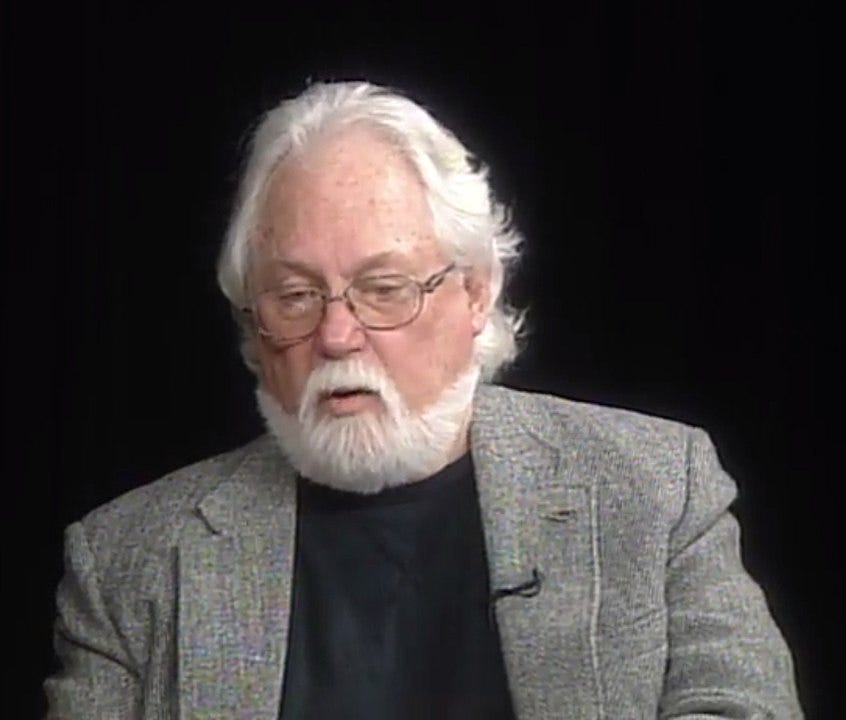

The Author: Robert Michael Pyle & Me

This week’s newsletter returns to The Library. Before diving into Wintergreen, I should be upfront about something. The last literary installment was a first: a living author. This one is also a first: a living author I’ve met. I have interacted with Pyle a few times, including a brief interview during which he shared with me his experience at a 1967 protest that I wrote about in An Open Pit Visible from the Moon. All my experiences with him confirms Pyle as deeply kind. That influences my reading of Wintergreen.

I had read bits of Wintergreen before, but this was my first direct trip from cover to cover. Lately, I have been interested in how authors write about distinct places, how they infuse their words with a sense of place. This can come in fiction or nonfiction, historical or contemporary times. I wanted to see the Willapa Hills through Pyle’s literary eyes.

Structure & Purpose

Wintergreen contains indictments and celebrations, but in its heart is an evocation of place, a no-name, out-of-the-way, hardworn, but beautiful place, rendered with care.

Pyle structures his book in four parts, each with four chapters. It’s an effective symmetry, a cycle like the seasons — of the year and of life. It begins with a description of the hills, then moves to what lived among them, followed by the impact of intensive logging, and ends with the inhabitants’ responses to the ravaging.

Through each chapter and section, Pyle weaves his wisdom that transcends Willapa.

Accepting What Is

Although special to Pyle, there is little extraordinary about the Willapa Hills and therein is the first lesson.

The Willapa Hills rise to nothing more significant than themselves. To appreciate them requires that you recognize this fact and adjust your expectations accordingly. What you see is what you get.

Again and again, this wisdom insinuates its way through the landscape and the book. Accept what is; don’t bemoan what is not. (At least, don’t only bemoan what is not.) Pyle frequently encourages us to appreciate a place on its own merits, rather than comparing it to other places. Focusing our judging eyes on what’s before us rather than what’s in our mind’s eye will produce more appropriate judgments.

The very plainness about the hills makes them rich for Pyle. Few naturalists tracked up and down the mountains and river valleys before him, allowing Pyle free rein to make discoveries, something he proclaims as deeply satisfying.

A Way of Seeing Ecology

In the next section – on the species that inhabit the hills – Pyle is perhaps most comfortable. A renowned expert on butterflies and general naturalist extraordinaire, Pyle closely observes what lives in the hills and provides a strong literary model for how to do that. He writes knowledgeably and precisely, but not pedantically.

He finds more species than anyone expects. This is yet another lesson he teaches.

In 1975, Pyle overheard a student conversation at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies about how simple Northwestern forests were, ecologically speaking. Seeing native forests as simple meant the steps were short to viewing them commercially as monocultures. Pyle dispels such simplistic notions, categorizing surprising ranges of animals, plants, and fungi. Every step in these descriptions models how to closely observe nature.

What Wintergreen argues, in its structure and narration, is a way of moving in the world, of seeing, of observing, of noting richness. Pyle writes, “And in its very modesty as a butterfly place, it is a good place indeed to become a better, more rounded naturalist.” Pyle teaches, word by word, and even better, action by action. “And in such pursuits, the pleasure lies largely in the search itself,” he notes.

The timber companies tallied a different type of riches in these woods.

Seeing beyond Exploitation

Halfway through the book, Pyle’s prose shifts. To that point, he writes as a naturalist. Thereafter, he adds another persona. He remains the naturalist, the scientist and lover of nature, but becomes also a citizen, one outraged by the devastation caused by intensive logging. He is careful to note, several times, that he is not anti-logger or anti-logging, just against the method of logging he sees in the Willapa Hills. As he notes about one company’s land, “the public interest in the forest resource has been miscarried in every way I can think of.”

[A side note: This book was first published in 1986 and so appeared at the height of the Pacific Northwest logging boom, just before a convergence of events that sharply curtailed logging. Across Pyle’s region, and across the valley from where his house sits in fact, he witnessed massive cutting.]

Pyle relentlessly criticizes the careless exploitation he observes. Part of this criticism stems from the natural knowledge still to be learned from the woods. They were disappearing so quickly that the lessons might not ever be discovered.

In the face of this, Pyle tries to cope and find productive ways to engage with his adopted region. “I am able to edit (not ignore) the ugliness necessary to the logging economy, to an extent, in order to enjoy what’s left,” he says. “But I cannot edit the gross abuses that I don’t believe are necessary. And I am a part of this community, albeit a relative newcomer.”

Pyle notes how hard it is for a naturalist to live in a ravaged landscape. His opening lesson remains prudent, though. Enjoy what is, what can still be found – such as what richness can be found in stumps – without being immobilized by all that is lost. A less wise man, a less patient one, might have given up and only raged.

Slouching Toward Stability

The Willapa Hills in the early 1980s meant hollowed out forests and hollowing out communities. Pyle steps in the timestream at a point when it might have been tempting to write off the region as a decaying place with no future. But, of course, Pyle is an ecologist and is filled with self-described “cosmic optimism.”

With his training and disposition, Pyle ends the book with a meditation on renewal. He writes evocatively about senescence in the woods, the good that comes from slow decay and how it rejuvenates the world. The tragedy he sees in the forest and the communities that rely on them is an arrested development. Both are prematurely made to die. An economy that looks to the short term and that requires fast results cannot abide rotting senescence. Trees and towns must be hurried along in an unnatural way.

Peaceful, creative stability makes more sense than rapid growth that outstrips its resources and is bound to bust again and again.

Such wisdom. Pyle wrote those words about human communities, but the lesson emerges out of ecology. Thinking like a naturalist means seeing cycles and on a scale determined by natural logic, not capitalist dreams.

Remaining Wintergreen

Enjoying Bob Pyle’s Wintergreen comes easily. His affection for his place, Willapa Hills, is infectious. I find it inspiring to observe experts at work doing the thing they enjoyed enough to master the task. Wintergreen is a masterwork.

“Only in winter, I believe, can one feel the full force of the rain that makes Willapa wintergreen in every sense.”

Closing Words

Robert Michael Pyle participated in a 1967 protest outside Darrington, Washington, when Justice William O. Douglas came to town. Douglas came to generate attention to Kennecott Copper Corporation’s desire to construct an open-pit mine in Glacier Peak Wilderness. This is the episode that started me on the research journey that led to my book, An Open Pit Visible from the Moon. That’s the place to find out more.

During my research for that book, I encountered this letter that I’m partially reproducing:

Although distant in geography, the pressures on the California Redwoods were not altogether dissimilar to what occurred in southwestern Washington. You can read an article I wrote about that here to learn more about politics of logging.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

A favor?

Would you consider doing me a favor? Word of mouth and personal connections help Taking Bearings spread and succeed. If you enjoyed this, there are few ways you can help make it more successful. Below, you can press the Like button. (I’m also happy to have comments, so drop a note in there if you would like.) If you are able, I’d be grateful if you upgraded to a paid subscription. If you know others who are interested in these sorts of topics, forward them the newsletter with encouragement to sign up. Thank you for all your support; I’m genuinely honored to have so many readers.

Taking Bearings Next Week

As you know, after The Library comes The Wild Card, and I have something new in store next week. For a long time, I’ve hoped to get other voices into Taking Bearings, so next week we’ll have just that. Another writer and I converse about history, place, and writing — and maybe about making a better world! I think you’ll enjoy it. Stay tuned!

Thanks for your writing In general and this piece in particular. I really appreciate the focus on a loved place and the changes--both hurtful and benign--that occur there. I'd like to share some of my writing about the San Juans with you; may I send you my three histories of the archipelago (Lime, Island Farming, and Island Fishing)?

Boyd Pratt

Thank you for this - it was heartbreaking to witness that time, and there is still so much to learn and help heal. I agree about Mr. Pyle’s writing, and was unaware of this book, so will look it up - keep at your own fine work!