Tomorrow is the 75th anniversary of when a deadly fog suffocated a Pennsylvania town, killing 20 people immediately (and shortening the lives of others for years afterward). It also sickened 6000 people, almost half the town. Chances are you have never heard of it, but it’s worth knowing. I want to share the story for this week’s edition of The Classroom. Read on!

Place of Disaster

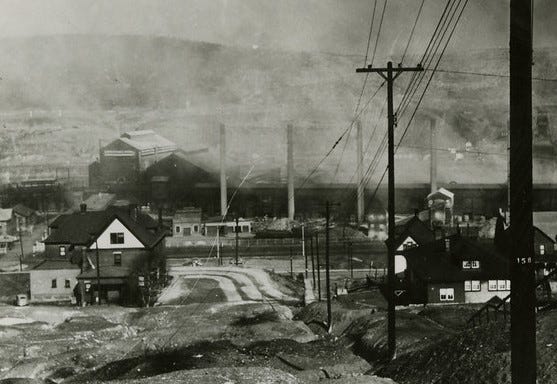

In the mid-20th century, south of Pittsburgh, hemmed in by hills and caressed by the Monongahela River, Donora, Pennsylvania, proudly housed three mills—a steel plant, a wire plant, a zinc-and-sulphuric acid plant—where two-thirds of its men and plenty of its women worked. With the river and hills and small-town size (12,300), it might have been an idyll, but its economy precluded that—and produced a disaster.

A writer in an award-winning article reported that outside of town were “sidings and rusting gondolas, abandoned mines, smoldering slag piles, and gulches filled with rubbish.” He continued, “It is treeless and all but grassless, and much of it is slowly sliding downhill. After a rain, it is a smear of mud.” And that was a typical scene.

On October 26, 1948, an atypical scene emerged.

The Fog

Fog clamped down on the hill-bound town. The writer mentioned above, Berton Roueché in the New Yorker in 1950, described “a sickening smell, almost a taste . . . [a] bittersweet reek.” One witness told Roueché, “You couldn’t see your hand in front of your face, day or night. . . . I drove on the left side of the street with my head out the window, steering by scraping the curb.” It was worse than normal, but being fogged in, rather smoked in, happened regularly. One Donora resident told Roueché, “Jesus, in a town like this you’ve got to expect fog. It’s natural.” That is, until people got sick. Really sick.

People collapsed after struggling to breathe. Doctors and nurses fielded endless calls of people with abdominal pain, headaches, vomiting, choking, even coughing up blood. Despite trying to persist—the regular town Halloween parade and high school football game proceeded as scheduled—Donora struggled. Because of the scale of acute sickness, no one realized quite how bad it was until the rain came and, figuratively, washed away the fog away by Halloween and looked around. Eighteen dead and two more in the weeks just after. That demanded an explanation.

What Happened?

What followed was a major investigation under the Public Health Service, the first large epidemiological study of an environmental health disaster. A temperature inversion caused the fog, but that didn’t explain the illness. Other inversions had occurred without resulting in deaths.

The mills for their part were confident that their activities did not cause the problems. And the study bore that out, sort of. It could not definitively identify what caused the toxicity. All the component gases known to be irritants had been in “safe” ranges. Perhaps it had been a combination? No one could be sure. One researcher concluded, “One of the most important results of the study is to show us what we do not know.” The adopted conclusion was the fog was “a one-time atmospheric freak,” according to the deputy head of industrial hygiene for the Public Health Service.

Freaks of nature, it might be pointed out, cannot be planned for, and changes in industrial practice aren’t required. The mills never accepted any responsibility.

More Hindsight

In 2002, Devra Davis published When Smoke Ran Like Water: Tales of Environmental Deception and the Battle Against Pollution. A scientist and Donora native, Davis used the example from her hometown to open her penetrating book.

We do a terrible job studying environmental causes of health problems, Davis argues, especially because those tend to unravel after years of exposure, not one, freakish event. This failure was especially true in the 1940s. Davis notes that no one measured pollution levels in Donora for two months. She also points out that at least fifty more people died in the months after, not used in the tally of deaths due to the deadly fog. A decade later, Donora’s death rate remained elevated. Davis’s grandmother lived through the fog, but experienced two dozen heart attacks in the following years. She also was not counted as a victim.

The point? Death and acute sickness during one event masks the chronic problems breathing polluted air. These effects are hard to measure, and for most of our history, no one even tried to.

Legacy

If you look up the deadly fog of Donora, you are likely to learn all of this. Many writers attribute the deadly smog to triggering political attention. The museum in Donora dedicated to commemorating this episode includes a sign: Clean Air Started Here. The investigation by the Public Health Service may not have concluded the definitive cause, but it generated enough interest that cleaning the air became a policy goal. By 1963, Congress passed the Clean Air Act. Quite the (sad) legacy.

Postscript

Most funerals were held on November 2, and the town undertaker told Roueché, “I think I have never seen such a beautiful blue sky or such a shining sun or such pretty white clouds. Even the trees in the cemetery seemed to have color. I kept looking up all day.”

Closing Words

The sort of urban pollution topics this story represents does not form much of my work. However, I worked with a student on a project that applied the notion of acute versus chronic conditions to a forest conservation project. You can find it here.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

Next week is time for The Field Trip, and I am headed out of town, so I may report on a new place. Stay tuned!