“If we do not serve what coheres and endures, we serve what disintegrates and destroys.”

–Wendell Berry, “Two Economies”

My college roommate read Wendell Berry’s 1977 classic critique of modern agriculture The Unsettling of America in his first-year composition course. Having just left a farm, I could not see any reason to be interested in such a book. I do not recall what my roommate thought of it, but Berry’s name stuck in the folds of my brain, periodically to resurface.

About a decade ago, I finally broke down and started reading Berry seriously, getting to Unsettling a few years ago. I have routinely found Berry to be provocative. Although you can read Berry to try on some agrarian nostalgia, a salve for bruised up modernity, I think he is more challenging than comforting. Berry’s vision of society is, I think, radically conservative.

For The Library this week, I dipped into Berry’s oeuvre to read “Two Economies,” an essay that first appeared in a Baptist theological journal in 1984 and then was reprinted in his 1987 book Home Economics. There’s nothing like holiday season to inspire reading about economics. Read on!

Wendell Berry’s miniature biography

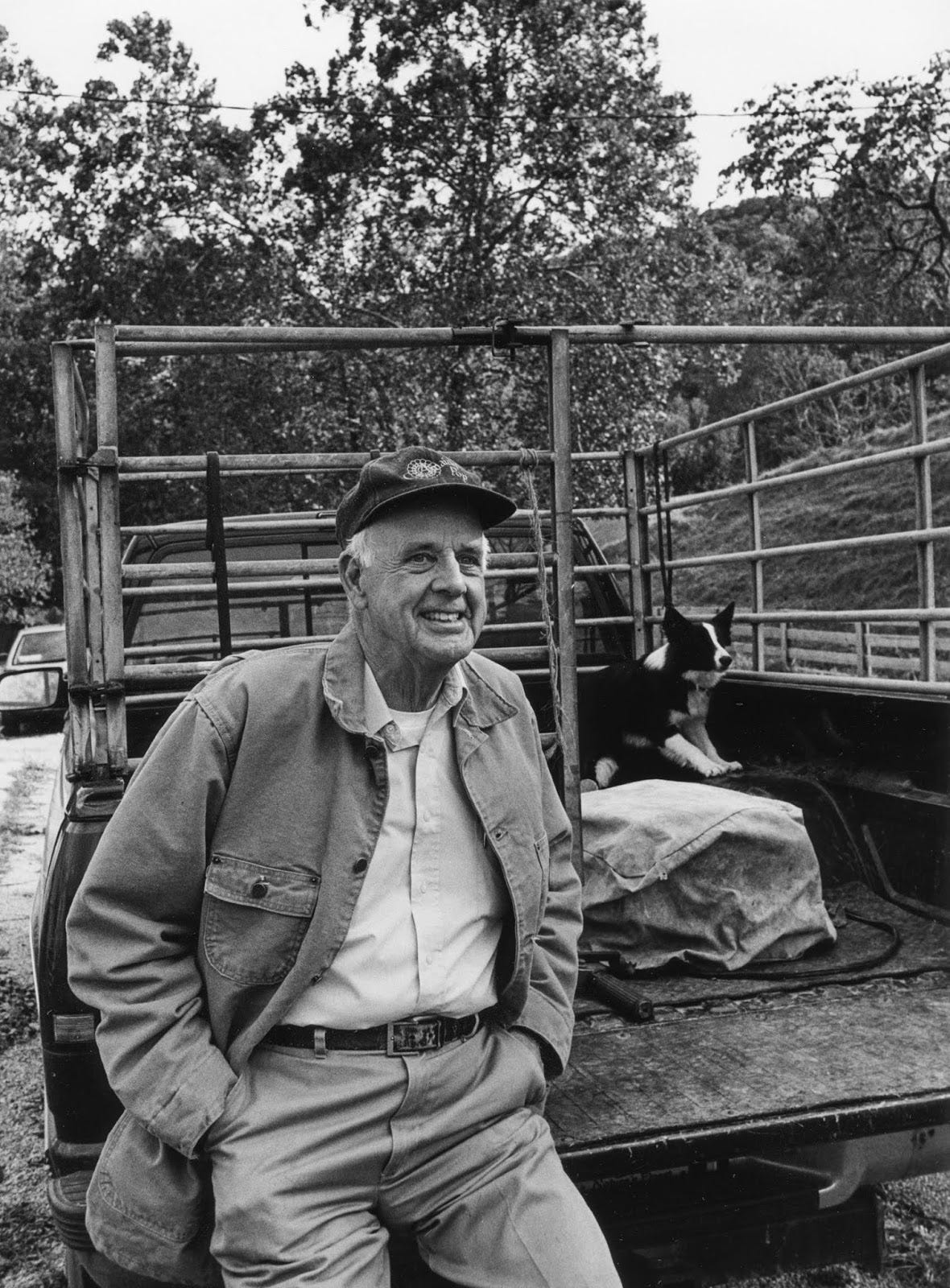

If you don’t know, Wendell Berry is a poet-farmer from Kentucky. For most of his life, Berry has remained in the small community along the Kentucky River where he grew up. He began publishing books in 1960 and has not stopped yet at age 89. Mostly known for his agrarian essays, Berry explores the proper relationship between society and the land in poetry and prose. A Christian, Berry weaves his writing with a religious philosophy and conservative sensibility. However, because much of modern American life is profoundly unsettled, his conservatism takes on a radical tinge. It is this mix that always forces me to think when I encounter Berry’s mind on the page.

The Great Economy and the little economy

In his essay, Berry proposes that two economies exist. He calls one the Great Economy, although he first introduces it as the Kingdom of God. The other he calls the little economy (and sometimes the industrial economy).

The Great Economy is expansive, all the mystery and complexity of the living world is contained within it. It is the world beyond us, the world that contains us. The Kingdom of God. The Tao. The Great Economy helps the concept become more universal or what Berry describes as “more culturally neutral.”

Berry identifies five principles of the Great Economy, paraphrased here:

It includes everything.

Everything in it is connected to everything else.

People do not—and cannot—know everything about it and how it is ordered.

Even though people cannot understand the pattern, severe penalties fall on those who violate it.

We cannot foresee an end to this economy.

The mystery that rushes through those principles is why Berry sees this primarily as a religious tradition—and, presumably, why it originally appeared in Review & Expositor. For human society, comporting ourselves to the Great Economy and its rules is necessary for a “good economy.”

The little economy, by contrast, sees nature basically as a fund, a storehouse to mine, to extract from. An industrial economy seeks control, not limits. Anything that does not fit the little economy becomes defined as “waste” or “wild” or “disordered.” In other words, it is assigned as outside the system, without value. But we know from the Great Economy that nothing can be outside or disconnected. To pretend otherwise is hubris, and the Bible and Greek mythology and other wisdom traditions are littered with stories about the consequences of hubris.

The implications are clear, as Berry describes them:

Once we acknowledge the existence of the Great Economy, however, we are astonished and frightened to see how much modern enterprise is the work of hubris, occurring outside the human boundary established by ancient tradition. The industrial economy is based on invasion and pillage of the Great Economy.

This is a stark interpretation, the kind that Berry is known for.

Neighborly

Although Berry comes from a Christian perspective, he offers a catholic formulation, thus making it more widely applicable—at least to those still willing to consider moral precepts in guiding our behavior. For those of us who spend time thinking about proper human-earth relationships, the idea that you cannot escape the Great Economy seems fundamental, even though many keep putting it off.

How can we stop putting it off? How can we think about this?

As a writer, Berry is adept with metaphors. Berry encourages us to think of living in a neighborhood, another word in this context for ecosystem. What we need, then, is to be neighborly, he says.

Part of being neighborly and living ethically is limiting ourselves. Americans especially scoff at limits. Living without limits is part of our much vaunted freedom. But this leads to dangerous separation, as Berry enumerates:

The industrial economy requires the extreme specialization of work—the separation of work from its results—because it subsists upon divisions of interest and must deny the fundamental kinships of producer and consumer; seller and buyer; owner and worker; worker, work, and product; parent material and product; nature, and artifice; thoughts, words, and deeds.

I might add, the separation of neighbor from stranger.

We cannot afford to deny the Great Economy while pursing our little economy. We cannot deny that we share the earth in common and violating nature’s rules will produce consequences—just as we cannot afford to deny the needs and dignity of all who live in the neighborhood.

If humans choose to live in the Great Economy on its terms, then they must live in harmony with it, maintaining it in trust and learning to consider the lives of wild creatures.

I have no doubt that Berry meant this literally and metaphorically. I hope we will all consider the lives of “wild creatures” and our other neighbors.

Closing Words

I’ve spent much of the last year getting to know a few farmers and agricultural issues near my new home. Much of that writing has been for a local nonprofit, and you can find some of those stories scattered here among some stories by other writers. I’m confident that many farmers consider issues Berry writes about (and plenty don’t).

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Announcements (Discount and Lecture)

A reminder that I’m offering a 20% discount between Thanksgiving and New Years for subscribers to Taking Bearings. I hope you’ll consider supporting my work and enjoying access to extra features including a monthly interview with another writer or artist.

A friend who I interviewed here, David B. Williams, will be presenting material based on his great book Homewaters about Puget Sound at the Community Resource Center of Stanwood-Camano. Details here for the event this coming Saturday. For local folks, I encourage you to make your way to the presentation.

Taking Bearings Next Week

Back to The Wild Card next week. Who knows how wild it will be? Stay tuned!

This is fantastic! I'm so glad I found you. I'm starting a Walden reading project to engage folks in 10 minutes of Walden per day. I'm also beginning a Walden-style sabbatical at a cabin my dad built in the Ozark woods. I really look forward to more of your writing to help me think about things to focus on when I'm in the woods.

Thanks for the shoutout and for your thoughtful words about Wendell Berry, long someone I have admired and read, with great enjoyment.