Growing up near Seattle in the 1970s meant many trips to the city featured the Seattle Center and the Space Needle — at least viewed from the interstate. In other words, a key part of Seattle was the aftermath of the Seattle World’s Fair in 1962, also known as the Century 21 Exposition. Although I recognized the Space Needle, the Coliseum, and the Pacific Science Center, I did not understand these were legacies from that fair.

There were other legacies I remained ignorant of, too. I just learned about another one: the First World Conference on National Parks. It’s an ideal topic for The Classroom. Read on!

“Nature Islands for the World”

On the Fourth of July, 1962, Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall addressed the First World Conference on National Parks at the Olympic Hotel in Seattle. The Keynote Address, titled “Nature Islands for the World,” reads as a fairly typical text for a conservation-minded politician in the 1960s. That is, it bounced a bit around topics, included some pithy slogans, and provided a call to action.

The speech occurred halfway through the conference but served as the introduction to the published proceedings, because it conveyed the common themes well (and probably because of Udall’s political position).

Udall, who the next year published The Quiet Crisis, saw the earth as vulnerable to technology and population — pretty common assessments in the early 1960s. The conference served a good sign to Udall that not all people worldwide worshipped the “false gods of materialism.” Too many people around the industrialized globe developed “a moral and spiritual sickness that results from being on the earth, yet not a part of it,” he thought. National parks and protected areas, Udall argued, helped preserve the conditions that would protect natural resources and promote human thriving.

This required work, both bold and prosaic. “We are the architects who must design the remaining temples; those who follow will have the mundane tasks of management and housekeeping,” said Udall in a rather self-aggrandizing characterization. He called for a “Common Market of conservation knowledge and endeavor” where expertise and efforts might freely cross the globe. Perhaps altogether, the work to expand parks could help create a new sense of values and a “conservation conscience” that Udall (and presumably many others in attendance) thought was necessary.

Contexts, National and Global

You could find few samples from the era that represent as well as Udall’s comments the ideas conservationists shared at the time. Americans were immensely proud of their (perceived) world leadership in national parks conservation.

Conrad Wirth, the National Park Service director, gave an opening speech in which he expressed some of that pride. National parks preserved foundational influences that made the United States as strong as it was. Parks contained “the same wonderous [sic] exposure that our forefathers experienced,” he said, while acknowledging other nations would necessarily have different influences and needs that they needed to make their national parks serve their unique needs.

For days, 145 delegates from 63 countries, along with more than 100 Americans, gathered in focused sessions to advance how to do that. They discussed general principles, as well as scientific, economic, and cultural elements of parks. Topics also included the best use of resources and how to administer protected areas and develop international coordination and implementation. Typical conference fare, perhaps, but it was the first of its kind.

At the time, the National Park Service was asserting its global leadership. The previous year the agency created its Division of International Affairs as one outward indication of this activity. However, leadership for this first conference came from outside the United States. The idea was first raised by Tsuyoshi Tamura, a landscape architect from Japan who helped popularize the idea of national parks there. Tamura broached the topic at a meeting of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). The IUCN joined with UNESCO and other international and American sponsors to put on this first conference.

This all suggests a moment of real transition in protected areas worldwide. But this conference remained strongly centered on the American tradition. In that respect, it could be viewed as the First World Conference on National Parks more than the First Ever World Conference on National Parks. In time, the IUCN became critical of some of the social costs of national parks, but that remained in the future in 1962.

World’s Fair

The future, though, was present in Seattle.

The Century 21 Exposition celebrated science, such as displaying Friendship 7, John Glenn’s Mercury spaceship. World’s fairs always project into the future, but in Seattle it looked very much like a continuation of mid-20th-century trends, like suburban shopping malls and theme parks.

Historian John Findlay has said that “like many Americans during the later 1950s, fairmakers took for granted that improvement implied ‘more of the same,’ rather than seeing tomorrow as an altogether different world.”1 The Monorail may have transformed a section of Seattle, but by the time I was a teenager, it connected a mall to an amusement park.

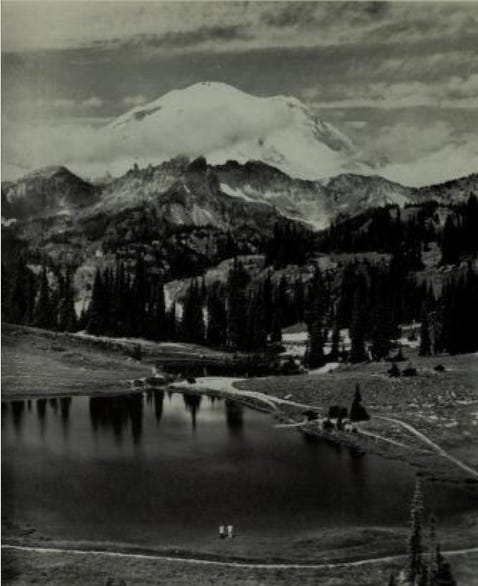

At this very moment, though, national parks enjoyed what is widely seen as their golden age, what historian Richard West Sellars said was when they “reigned indisputably as America’s grandest summertime pleasuring grounds.”2

It makes for a rich juxtaposition, or perhaps just a fitting complement.

In the Field Is Always Better

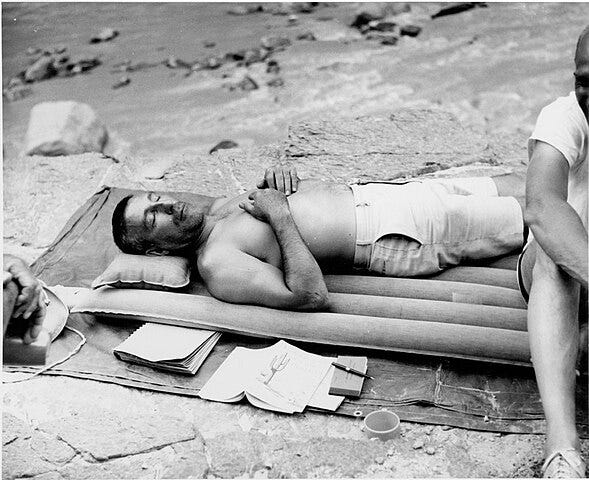

No matter how state-of-the-art the World’s Fair may have been or how nice downtown Seattle was, the First World Conference on National Parks’ preferred habitat was parks themselves.

Before the meeting, delegates headed to Mount Rainier and the nearby Snoqualmie National Forest. Afterward, they headed to the Olympic National Park, both to Hurricane Ridge and the coastal strip, a piece of land free from roads thanks to local activists (some of whom were part of the local arrangements committee). Later, 67 delegates from 40 countries stayed together, hopped on a train, and headed to Yellowstone and then south to Grand Teton National Park.

According to the published proceedings, “Beyond the scenic beauty and physical wonders of the national parks, the trips had afforded an opportunity to observe how biology, ecology, human history, and archeology fit together in the National Park System. . . . Inspired, strong opinion was voiced that another conference, not necessarily the next one, should be held at the Yellowstone in its centennial year, 1972.”

The Second World Conference on National Parks became far more famous than the first, but you have to start somewhere. Seattle is a good enough spot to start from.

Closing Words

Relevant Reruns

This old newsletter is about that roadless ocean beach mentioned at the end of this week’s newsletter. This story tells about another occasion when a large group of leaders convened, hoping to solve some environmental problems.

New Writing

I have two new pieces to share this week in decidedly different genres. First, a personal essay I began back in 2019 finally appeared in South Dakota Review. It is called “Seeking Elk” and two versions can be found hosted on my website (a scan and a typescript). It is about my efforts to find bugling elk and what I found along the way.

I also have a new reported story in Salish Current about Farm to School programs in my local area that seek to connect local farmers and schools around healthy food.

As always, you can find my books, and books where some of my work is included, at my Bookshop affiliate page (where, if you order, I get a small benefit).

Taking Bearings Next Week

It is time for The Field Trip next week. Stay tuned!

John M. Findlay, Magic Lands: Western Cityscapes and American Culture After 1940 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 246.

Richard West Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 1.